In September 2013, the then Tesco chief executive Philip Clarke called time on a decade-long ‘‘space race’’ that had gripped the UK grocery giants. He said UK shoppers had fallen out of love with large out-of-town supermarkets and were switching their shopping habits towards online, click and collect, and little and often trips to smaller convenience stores.

The space race in UK food retail took off in the early noughties and quickly developed into a near obsession for bosses of the UK’s largest supermarkets. At the vanguard of this race, which was measured in square feet, was the UK’s largest supermarket, Tesco.

By 2003, Tesco operated almost 1,900 stores across the UK, giving it 20m sq feet of property. It had taken Tesco more than 80 years to reach this level since its formation in 1919. However, it took just another 10 years to double its footprint of UK stores to more than 3,700, to reach almost 46m sq feet of property by 2014.

Everyone did it at the time and there was a concern, I guess, that if you didn’t take that space then somebody else would, and you would be at a competitive disadvantage

Ultimately, this space race proved near disastrous for Tesco and culminated with the retailer recording a £6.4bn (€7.3bn) loss in April 2015 due to huge write-downs on its property portfolio. This was the largest financial loss recorded in UK retail history.

Looking back in hindsight, Tesco chair John Allan described the retail space race as “not a very good idea”, which left the grocery sector with far too much property and not enough customers.

“Everyone did it at the time and there was a concern, I guess, that if you didn’t take that space then somebody else would, and you would be at a competitive disadvantage,” said Allan in a rare interview in 2016.

Herd mentality

What Allan’s comments illustrate more than anything is the herd mentality that took hold in the UK retail sector during that period and what was perceived as the winning strategy for the sector. Tesco and the other large UK retailers have since largely worked through the financial issues created out of the space race but are still in the midst of cost-saving programmes.

However, it is interesting today to see a new type of arms race emerging in the food retail sector, not just in the UK but right across the globe. The advent of online retail has taken hold in recent years and established supermarkets the world over are working to try to avoid disruption from new online competitors they never had before, such as Amazon, Ali Baba and Ocado.

Amazon threat

On this side of the Atlantic in particular, supermarket bosses have been bracing themselves for an inevitable attack on Europe from Amazon. The e-commerce giant has disrupted everything from music to books to film, and it has made its intentions clear that food retail is the next frontier it plans to dominate.

What’s different to this new race in the online age is that no clear strategy or answer has emerged amongst the established supermarkets around how to solve the online question in the same way that building more stores was seen as the only way to win the space race back in the early 2000s.

Instead, what we are seeing today is a whole host of different strategies being pursued by established supermarkets to try to stave off disruption from e-commerce competitors.

The latest of these strategies was revealed this year when Sainsbury’s, the UK’s second largest supermarket, announced it had reached a deal to merge with Asda, the UK’s third largest supermarket. The new entity will become the largest retailer in the UK with a combined market share of more than 31%.

However, the real significance of the Sainsbury’s-Asda tie-up could be in what it means for the group’s online strategy in the future. Sainsbury’s reported a 7% increase in online food sales for its latest financial year, with the retailer now able to offer same-day delivery to 40% of the UK population from 102 stores.

Almost all online orders processed by Sainsbury’s are carried out by staff who hand-pick groceries from existing stores. Mike Coupe, chief executive at Sainsbury’s, says the addition of 200 Asda stores to the group will increase capacity for Sainsbury’s online grocery-picking operation.

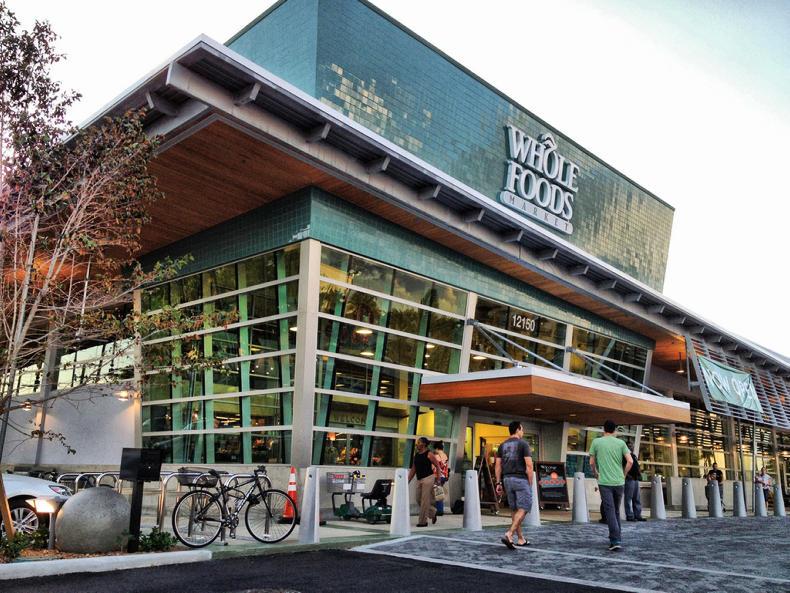

Whether this will work for Sainsbury’s remains to be seen but the acquisition of Asda has eased investor fears of a potential takeover by Amazon. The US e-commerce giant made its first move into bricks-and-mortar retailing in 2017 when it announced the $13.7bn takeover of US supermarket chain Whole Foods.

This move fuelled speculation in financial markets that a similar buyout was on the cards in Europe, with Sainsbury’s often mentioned as a potential target. Instead, Amazon’s first foray into Europe has been to partner with the French retailer Casino Group. The company has also signed a similar partnership with UK retailer Morrisons.

Amazon’s approach to food retail is interesting. With grocery spending accounting for about 50% of all retail sales, the e-commerce giant was always going to make a move into this sector.

However, Amazon’s strategy has evolved into a move downstream to bricks-and-mortar supermarkets just as established retailers are investing upstream in digital infrastructure and mobile apps.

Dark supermarkets

The other strategy on the table for the future of online food retail are dark supermarkets. Following the end of the space race, many of the largest UK retailers moved to build dark supermarkets, which are effectively grocery warehouses where online orders are processed.

Most supermarkets still pick the majority of online grocery orders from existing stores but the number of dark supermarkets is rising.

Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Waitrose have all opened dark supermarkets since 2014, in the expectation that 10% of all UK grocery sales will be ordered online by 2022.

At the forefront of dark supermarket development is Ocado, the UK online supermarket with sales of £1.4bn last year. The online retailer currently operates three dark supermarkets, or customer fulfilment centres (CFCs) as they are known, where thousands of robots zip around an enormous warehouse processing online grocery orders.

Ocado has recently completed construction of its fourth CFC facility located at Erith in southeast London at a cost of £250m. The Erith warehouse facility sits on close to 13 acres and will be the largest ever CFC built by the company.

Transformation

Interestingly, Ocado is trying to transform itself from an online grocer to a technology company that will supply the robots, hardware and software systems for established supermarkets to make the move to online.

For its 2017 financial year, Ocado generated just over 8% of its annual sales (£116m) and 3% of earnings (£2.7m) from the sale of proprietary technology solutions to other retailers.

The company plans to scale this side of its business to sell its robot technology to other retailers as it will deliver higher margins than traditional grocery sales.

Given the uncertainty around what the future of grocery retailing may look like, investors have bought into Ocado’s strategy to back its own technological solutions as a service for existing players rather than trying to disrupt an entire marketplace on its own.

Shares in Ocado have surged by more than 130% in the last six months with investors increasingly taking the view that the company is evolving into a technology pioneer.

The next decade is likely to bring major structural changes to the traditional grocery retail sector as online sales claim more and more market share. What the winning strategy will be remains to be seen but a new arms race is building between the traditional powers of grocery and online disruptors.

SHARING OPTIONS