It was hard to not be moved when we first arrived at our Lighthouse Farms community in Ethiopia. We had driven through barren mountain landscapes for hours on end, scenes where very little, if anything, wants to grow. But when we scaled the final pass, we witnessed a green valley opening up in front of us, a green tapestry of crops and shading trees. As we drove down to the base of the valley, the fields were a hive of activity, with farmers tending to teff, barley and orchards.

What made this valley so remarkably different to others we had passed through? The local guide explained that the answer lies in the people. With the help of support from Ireland (Irish Aid, UCC and Teagasc) and the German Development Agency (GIZ), farmers have come together to reverse land degradation with joint labour and shared byelaws.

They have agreed to keep livestock off the steep slopes to stop erosion. Farmers commit 50 days a year to community labour, building terraces and check dams, which fill the gullies with new fertile soil. Agreements have been made to allocate this new land among the farmers.

Even the landless farmers have a role – they are in charge of the crop nursery that produces planting material for the community. The result – a community that is a candidate for a UNESCO Human Landscape Heritage Site.

Working together

Throughout our global network of Lighthouse Farms, we find that it takes a village to manage sustainable farm systems. Our latest addition, a Lighthouse Farm community in India, became a success through the work of communal groups, while our Indonesian farmers have organised themselves in farmer field schools.

Through these community approaches, farmers share not only their labour and machinery, but especially their knowledge, insights and successes.

But how can complexity be managed on family farms that are so common in Ireland and other parts of Europe? Our Latvian caviar powerstation dairy-farm employs around 100 people, from vets to engineers to fish experts, in order to manage the many enterprises on the farm.

But few farms in Europe can afford such a workforce. So, how can other family farms navigate the labyrinth of sustainability?

Farmers have to manage information overload

It is important to remember that family farms do not work in isolation either. They work and communicate with many others, such as suppliers, processors, advisers, inspectors, neighbours, friends, colleagues, consumers, etc.

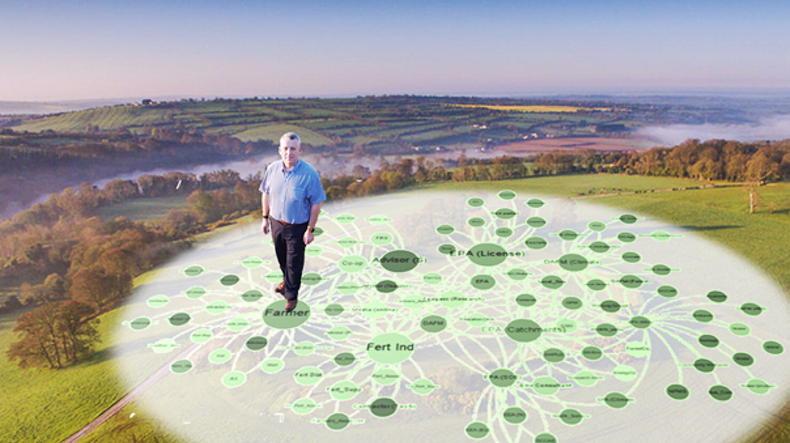

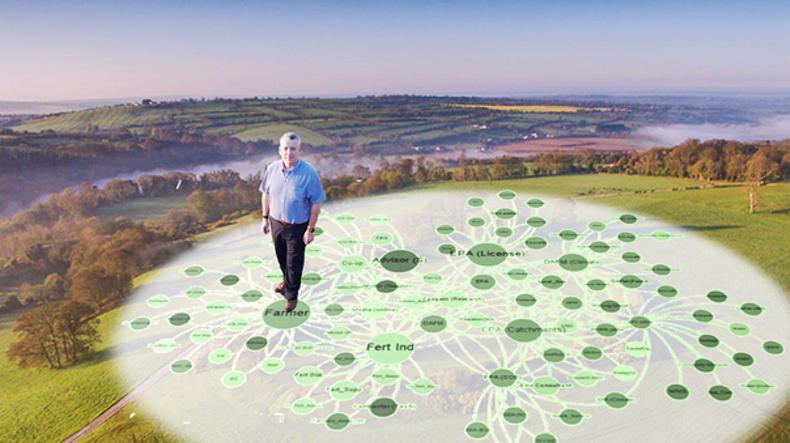

However, their communication is rarely integrated, and too often farmers receive an overload of conflicting messages on the many different aspects of sustainability (Figure 1).

Farmers have to be experts in many things, from agronomy to animal husbandry to finance to health and safety and bookkeeping. Now, we expect them to also become experts in climate change, water quality, biodiversity and nutrient cycling.

As a Dutch dairy farmer once told me: “Just as I was planning to invest in better housing to comply with the Nitrates Directive, my processor tells me I should have my cows out grazing for improved animal welfare. I no longer know the direction in which to develop my farm.”

Harmonising a fact-based approach

So how can we help farmers make sense of the many signals they receive from modern society?

We studied this question across three continents and arrived at three answers.

Automation, alignment

and affinity

Automation: technology has long been the farmer’s friend in making sense of complex data. The weather forecast is the simplest example of a technology that helps in daily decision-making. More recent decision support tools include nutrient management software, herd management systems and the soil navigator for sustainable soil management. Next up, artificial intelligence will allow technology to actively manage complex tasks. We have all grown accustomed to the sight of robots mowing our lawns and milking our cows. Our students are now training similar robots to recognise weeds from crop seedlings, to enable them to remove weeds while replacing herbicides or manual labour.

Alignment: but technology is not a full substitute for human contact – a lesson we have all learnt during the pandemic. The second way to help farmers make sense of sustainability is to make sure that we align the information that farmers receive. Instead of farmers receiving conflicting messages from different actors in society, there is a need for them to be aligned and bundled into a coherent set of on-farm advice. Affinity: our research shows that farmers across the world are most likely to act upon information when they trust the source. Depending on the country, these trusted sources can be advisory services, processors, regional authorities or NGOs. Key to a collective approach is that these trusted actors are equipped with both the resources and resolve to help farmers navigate the labyrinth of sustainability.Next month

The past year has taken its toll on people all around the world, and this is no different for our Lighthouse Farmers, not least our farmers in Ethiopia.

They find themselves in the midst of armed conflict and are now on the brink of severe food shortages. Indeed, the global network of Lighthouse Farms is very much a mirror of the world, with all its ups and down.

But this is not the first time that our farmers have faced adversity. In our next article, we will trace back the journeys of some of our farmers to learn how they tried and failed, only to try again.

In brief

Community power can be harnessed to help overcome significant adversity. Managing farming systems for a balanced environment is bigger than just any single farm.Technology can be used to help and automate certain processes. Farmers are confused when they receive conflicting messages and demands from different pillars of society.

It was hard to not be moved when we first arrived at our Lighthouse Farms community in Ethiopia. We had driven through barren mountain landscapes for hours on end, scenes where very little, if anything, wants to grow. But when we scaled the final pass, we witnessed a green valley opening up in front of us, a green tapestry of crops and shading trees. As we drove down to the base of the valley, the fields were a hive of activity, with farmers tending to teff, barley and orchards.

What made this valley so remarkably different to others we had passed through? The local guide explained that the answer lies in the people. With the help of support from Ireland (Irish Aid, UCC and Teagasc) and the German Development Agency (GIZ), farmers have come together to reverse land degradation with joint labour and shared byelaws.

They have agreed to keep livestock off the steep slopes to stop erosion. Farmers commit 50 days a year to community labour, building terraces and check dams, which fill the gullies with new fertile soil. Agreements have been made to allocate this new land among the farmers.

Even the landless farmers have a role – they are in charge of the crop nursery that produces planting material for the community. The result – a community that is a candidate for a UNESCO Human Landscape Heritage Site.

Working together

Throughout our global network of Lighthouse Farms, we find that it takes a village to manage sustainable farm systems. Our latest addition, a Lighthouse Farm community in India, became a success through the work of communal groups, while our Indonesian farmers have organised themselves in farmer field schools.

Through these community approaches, farmers share not only their labour and machinery, but especially their knowledge, insights and successes.

But how can complexity be managed on family farms that are so common in Ireland and other parts of Europe? Our Latvian caviar powerstation dairy-farm employs around 100 people, from vets to engineers to fish experts, in order to manage the many enterprises on the farm.

But few farms in Europe can afford such a workforce. So, how can other family farms navigate the labyrinth of sustainability?

Farmers have to manage information overload

It is important to remember that family farms do not work in isolation either. They work and communicate with many others, such as suppliers, processors, advisers, inspectors, neighbours, friends, colleagues, consumers, etc.

However, their communication is rarely integrated, and too often farmers receive an overload of conflicting messages on the many different aspects of sustainability (Figure 1).

Farmers have to be experts in many things, from agronomy to animal husbandry to finance to health and safety and bookkeeping. Now, we expect them to also become experts in climate change, water quality, biodiversity and nutrient cycling.

As a Dutch dairy farmer once told me: “Just as I was planning to invest in better housing to comply with the Nitrates Directive, my processor tells me I should have my cows out grazing for improved animal welfare. I no longer know the direction in which to develop my farm.”

Harmonising a fact-based approach

So how can we help farmers make sense of the many signals they receive from modern society?

We studied this question across three continents and arrived at three answers.

Automation, alignment

and affinity

Automation: technology has long been the farmer’s friend in making sense of complex data. The weather forecast is the simplest example of a technology that helps in daily decision-making. More recent decision support tools include nutrient management software, herd management systems and the soil navigator for sustainable soil management. Next up, artificial intelligence will allow technology to actively manage complex tasks. We have all grown accustomed to the sight of robots mowing our lawns and milking our cows. Our students are now training similar robots to recognise weeds from crop seedlings, to enable them to remove weeds while replacing herbicides or manual labour.

Alignment: but technology is not a full substitute for human contact – a lesson we have all learnt during the pandemic. The second way to help farmers make sense of sustainability is to make sure that we align the information that farmers receive. Instead of farmers receiving conflicting messages from different actors in society, there is a need for them to be aligned and bundled into a coherent set of on-farm advice. Affinity: our research shows that farmers across the world are most likely to act upon information when they trust the source. Depending on the country, these trusted sources can be advisory services, processors, regional authorities or NGOs. Key to a collective approach is that these trusted actors are equipped with both the resources and resolve to help farmers navigate the labyrinth of sustainability.Next month

The past year has taken its toll on people all around the world, and this is no different for our Lighthouse Farmers, not least our farmers in Ethiopia.

They find themselves in the midst of armed conflict and are now on the brink of severe food shortages. Indeed, the global network of Lighthouse Farms is very much a mirror of the world, with all its ups and down.

But this is not the first time that our farmers have faced adversity. In our next article, we will trace back the journeys of some of our farmers to learn how they tried and failed, only to try again.

In brief

Community power can be harnessed to help overcome significant adversity. Managing farming systems for a balanced environment is bigger than just any single farm.Technology can be used to help and automate certain processes. Farmers are confused when they receive conflicting messages and demands from different pillars of society.

SHARING OPTIONS