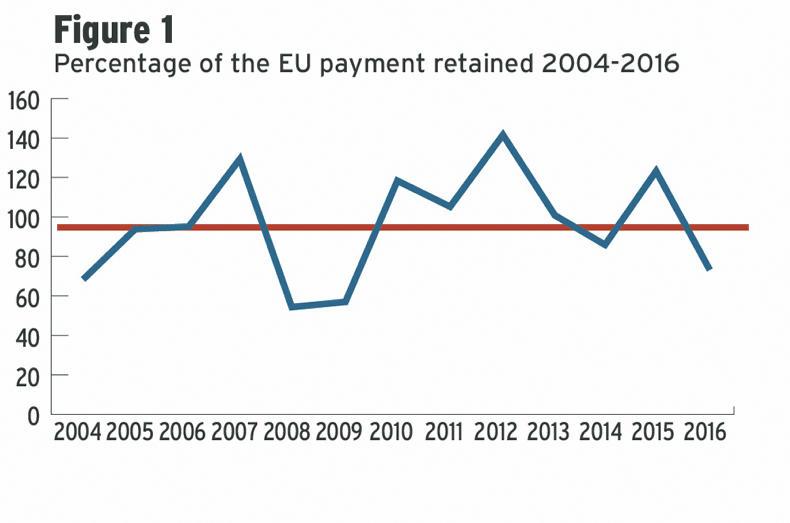

Coping with the challenging times associated with low grain prices was very much the central theme of the morning session at the Teagasc National Tillage Conference last week. Perhaps the slide that best sets the scene for the times we are in was one presented by David Walsh-Kemmis which showed the percentage of the farm payment that could be retained within his farm business.

This slide (Figure 1) clearly shows that only in six of the past 13 years could he retain all and add to his payment level. In five of these years, including 2016, a proportion of the cost of running the farm had to be made from the EU payment. In those years, this farm did not wash its face, so to speak, and would have operated at a loss in the absence of that EU payment. This was on a 163ha tillage farm with all owned land and a high proportion of premium-bearing crops.

David’s story was very interesting. He came to farm at home in Stradbally from a career in computer science.

“Computers are predictable and controllable”, he said. The move into a profession where most aspects of the business are unpredictable bordered on chaotic. So he very quickly decided to concentrate on the things that he could control to some degree and to attempt to manage the other risks.

The immediate decision was to try to move away from commodities towards crops that carried a price premium. One such crop was gluten-free oats on contract to Glanbia. David said that this involves more paperwork and it is really a two-year planning process but it is also the best-paying crop on the farm.

The other main crop is malting barley and this accounts for 60% of the farm area. While there are real issues with specifications like protein level and grain skinning, David said that he cannot ignore the premium level. For him yield level is higher than had been achieved with feed barley and he lost 50% of the premium in 2016 (other growers lost much more). In planning and budgeting he suggested that one must bargain on losing 20% of the premium every year for some reason relating to specification.

David said that he also experimented with different types of lupins in 2016. The blue lupins were manageable but low yielding and would only make sense if the price was very high. The white type were better yielding but were far too late-maturing to be suitable.

He has also grown quinoa on trial for Glanbia and he found this to be a good crop option, at least in 2016. It was very easy to manage, he said, mainly because there are no sprays that can be used but the crop is good at smothering weeds.

He is also now growing cover crops based mainly on fodder rape and leafy turnip and much of this is then sold for grazing. This is unquestionably good for the land but only time will tell as to how it impacts on protein content in malting barley. Some of the catch crop is grown under GLAS but he also has some other areas where he is looking at other species.

Brewery

Being a malting barley grower with a big interest in brewing, David has now moved to establish his own brewery in the traditional farm buildings. His Ballykilcavan Brewery brand is an effort to give the farm viability into the future. All the grains involved will be grown on the farm, malted in Athy and brewed in Ballykilcavan.

David has also acted to attempt to minimise price risk through forward-selling. He has been doing this since 2012 and, with the exception of the first year, he has recorded a price benefit relative to harvest price in all subsequent years. His price benefit ranged from €15 to €20/t and he reckoned that forward selling has earned him an additional €30,000 farm income in the past four years.

Most growers were introduced to forward selling in 2012. In the early part of that year, prices were quite reasonable, with wheat around €190/t. However, prices rose considerably closer to harvest and a bad growing year produced very poor quality, leaving many of the contracts unable to meet the quality spec with associated consequences. This experience gave forward selling a bad name for most growers and there has been very little forward selling since that year.

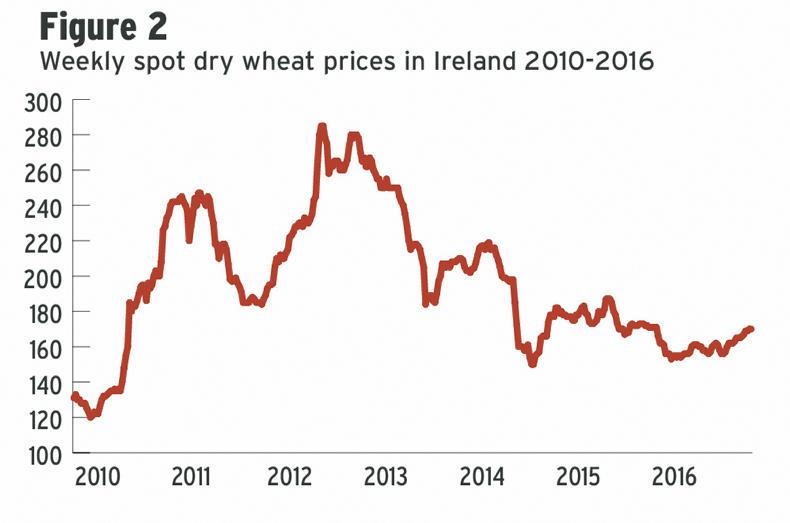

At the conference, I showed in graph format (Figure 2) the movement in spot wheat prices since 2010. Spot is the price available to a grower with grain in stock on the day of sale and assumes use with a short period. This graph shows significant price movement over the years and it also shows that high prices normally cure high prices.

The high prices in 2010 and 2012 were quickly followed by a significant drop to the following harvest. It is noteworthy that in the following years price bottomed out at around €190/t. But in the next three years (2014-2016) spot wheat price levels fell further due to the continuous oversupply situation and the building of global stocks.

I also looked at the forward prices that were available for November delivery in different years. Price movement in 2012 showed that no forward sale would offer a price benefit because of the rapid price rise prior to harvest. This experience, plus the issues with spec, has been a major factor in discouraging growers to sell forward in subsequent years. Most forward business on wheat was done at €190-€195/t but dry harvest price exceeded €260/t. Who would be happy to get €190/t today?

The spot price in 2012 (Figure 2) indicated the probability of a fall in 2013 and the forward prices on offer reflected that. Prices fell right up to harvest 2013 and by mid-June forward selling would have added at least €20/t on average to those sales. And that was relative to a harvest equivalent dry price of over €190/t.

In 2014, all prices rose between February and May but then fell to around €170/t for dry wheat at harvest. The result was that forward sales in January added about €13/t over harvest price but then averaged over €30/t between February and May. Even in 2015, when most growers had excellent yields and harvest price was around €165/t, forward selling could have added between €7 and €25/t right up to August.

For this reason, forward selling must be seriously considered by professional growers, either green or dry. With current surplus levels being so high, growers need to watch the market for spikes driven by things that change sentiment in the short term, as these might provide a forward selling opportunity to help increase average selling price.

It’s all about the average price whether it rises or falls after you sell.

While price is ultimately influenced by supply and demand, many other factors can influence sentiment to alter the the daily or hourly price.

Traders are influenced by reports of planting intentions, weather post establishment, snow cover, frost kill, dryness issues, political decisions, currency and especially drought. Any of these things can influence forward prices for an hour, a day or a week but then oversupply dominates again. But such reaction can provide a spike in prices that makes a sale worthwhile and it is up to each individual to know about, and avail of, such opportunities.

Grain consumption

The world has just had four-in-a-row record big harvests. While total grain consumption has increased over the years it has not been able to keep pace with production over the past four years and stocks are increasing. These stocks will help lessen the impact of any shortfall in production, should one occur in 2017, and so the prospects for any significant increase in prices must be regarded as low for the moment.

However, this could change as climatic factors in particular are bound to impact on production capability at some time. But it is also possible that we could be the victim of a low yield year and so we must always aim to keep production costs as low as possible.

Could Irish-grown wheat be used to displace imported maize in Irish whiskey production?

This was the question behind the title of the paper presented by Sarah Clarke of ADAS. While Sarah was speaking about wheat for industrial alcohol or bioethanol production, the principles behind her presentation could equally apply to beverage production.

Sarah explained that around 2m tonnes of wheat is currently being used in Britain for bioethanol production for fuel use.

There are some but relatively few differences between bioethanol and spirit production and alcohol yield is a major factor in its competitiveness.

Sarah explained that wheat for distilling needs to be as high as possible in starch content and be as low as possible in protein content.

In most regards, this is the exact picture of Irish wheat. Sarah explained how low protein content helped to increased alcohol yield per tonne but the baseline level for her research was about 11%, a level that would be virtually impossible to achieve in an Irish winter wheat. Irish wheat is generally closer to 9.5% protein.

Starch

Average British wheat tends to have an alcohol yield of about 435 litres per tonne. Maize alcohol yield is generally regarded as being about 20 l/t higher than wheat but we need to ascertain what the alcohol yield of a 9.5% protein wheat would be.

It seems possible that good Irish wheat could well have a similar alcohol yield to imported maize which is likely to cost our distilling sector considerably more than native wheat.

Variety also matters to alcohol yield, Sarah said. Research has shown that soft endosperm wheat varieties tend to have higher alcohol yield per tonne but there are variety differences in this regard. However, simple evaluation might well provide a good indication of the potential alcohol production capacity of current and new varieties to be grown here.

Sarah also commented that triticale was assessed as a source of starch for alcohol. Laboratory tests indicated that its alcohol yield might be slightly lower than suitable wheat but it was still deemed to be a suitable source.

Expanding break-crop market

Ireland used very little break crop in its total tillage area. While this issue has been addressed at recent tillage conferences the area sown to break crops is not expanding.

Break crops can bring many advantages to an overall rotation through having a disease or pest break, possibly contributing to soil fertility and generally adding to soil structure improvements. But the crop itself may not always add directly to improved economics.

Speaking at the conference Dermot Forristal addressed these issues and showed that it is important to value the crop within the rotation.

Based on figures from previous experiments, adjusted to current prices, Dermot showed that a continuous wheat rotation averaged €36/ha profit compared to €212/ha for a winter wheat, winter barley, oilseed rape, winter barley and beans rotation.

This compared with €187/ha from a winter wheat, winter barley, oilseed, winter wheat and winter oats rotation.

While the rotation with beans is benefiting from the protein aid, Dermot said that the average profit would be somewhat lower but the benefit to the following wheat would still be there and be substantial.

While bean area has increased to utilise all of the area support, Dermot said that the utilisation of the crop at processor level is slower and has led to stocks.

He emphasised that marketing must be a coordinated approach involving everyone along the supply chain. There are real issues that need to be addressed before the sector can move on but there is a potential market size for over 400,000 tonnes in a well-developed market, even at a limited 10% inclusion rate in rations.

While there are some nutritional issues with beans, Dermot suggested that one of the main blockages to use is because there is little or no value placed on home grown traceable feed.

There is also potential to consider the human food market for this crop but this would involve exports and would have to be carefully managed and developed.

Oilseed rape is the other combinable break crop with potential to expand if there was a more sophisticated structure to the market. Over 80% of the current crop goes for animal feed with less than 10% going for cold-pressed food grade oil. And there is a somewhat similar amount used for niche markets.

While animal feed will continue to be an important part of the market the option to pursue higher value cold pressed oil markets, possibly even for the export markets, must be considered. This needs production and marketing support but it would benefit from having a potential unique selling point. He asked if there was potential in having an export brand to underpin individual brands to help do this.

A new guide to the growing, feeding, quality and purchasing arrangements for maize was launched at the conference.

This is a lovely publication directed at growers and users to help inform them of the husbandry requirements of growing the crop to help secure high output from this relatively expensive crop.

Kevin Cunningham of DLG chaired the group which produced the guide and he presented a brief description of its contents at the conference.

The section on growing introduces a new and simple method to guide growers as to the potential suitability of each of the varieties on the recommended list for planting in excellent, good or marginal sites.

Kevin emphasised that it is very difficult to get varieties that will produce their stated benefits every year and that only such varieties are recommended by the Department.

The feeding section deals with maize silage as a buffer feed, its use for indoor feeding of dairy cattle and its use in beef production systems. For maize to be useful on any farm it must contribute to farm performance, Kevin said.

Understanding quality in maize is a very important issue. Maize grown under plastic cover has higher and more consistent yield and starch levels. But achieving target dry matter and starch levels can be undone if the correct variety is not selected for specific sites.

Kevin made the interesting comment that maize quality is relatively consistent when the correct varieties are chosen for any site. Alternatively, the wrong variety can carry a penalty on farm performance.

A section of the new guide deals with the necessity for and benefits of a written contract where a grower and user are involved. Indeed, the guide contains an actual contract based on a base of 25% dry matter and 25% starch.

A third party is involved in such a contract and he/she can alter the actual price based on the actual quality in the delivered silage. So both parties are protected.

Kevin concluded by saying that maize does not suit every farm but this guide should certainly help protect both parties where the crop is to be grown on contract.

In summary

Every farm needs to continually evolve towards its future.There has been significant benefit from forward selling in most recent years.It may be possible to identify wheat varieties that are highly suitable for use in distilling.The industry needs to develop a coordinated approach to expand markets for protein crops and oilseed rape.

Coping with the challenging times associated with low grain prices was very much the central theme of the morning session at the Teagasc National Tillage Conference last week. Perhaps the slide that best sets the scene for the times we are in was one presented by David Walsh-Kemmis which showed the percentage of the farm payment that could be retained within his farm business.

This slide (Figure 1) clearly shows that only in six of the past 13 years could he retain all and add to his payment level. In five of these years, including 2016, a proportion of the cost of running the farm had to be made from the EU payment. In those years, this farm did not wash its face, so to speak, and would have operated at a loss in the absence of that EU payment. This was on a 163ha tillage farm with all owned land and a high proportion of premium-bearing crops.

David’s story was very interesting. He came to farm at home in Stradbally from a career in computer science.

“Computers are predictable and controllable”, he said. The move into a profession where most aspects of the business are unpredictable bordered on chaotic. So he very quickly decided to concentrate on the things that he could control to some degree and to attempt to manage the other risks.

The immediate decision was to try to move away from commodities towards crops that carried a price premium. One such crop was gluten-free oats on contract to Glanbia. David said that this involves more paperwork and it is really a two-year planning process but it is also the best-paying crop on the farm.

The other main crop is malting barley and this accounts for 60% of the farm area. While there are real issues with specifications like protein level and grain skinning, David said that he cannot ignore the premium level. For him yield level is higher than had been achieved with feed barley and he lost 50% of the premium in 2016 (other growers lost much more). In planning and budgeting he suggested that one must bargain on losing 20% of the premium every year for some reason relating to specification.

David said that he also experimented with different types of lupins in 2016. The blue lupins were manageable but low yielding and would only make sense if the price was very high. The white type were better yielding but were far too late-maturing to be suitable.

He has also grown quinoa on trial for Glanbia and he found this to be a good crop option, at least in 2016. It was very easy to manage, he said, mainly because there are no sprays that can be used but the crop is good at smothering weeds.

He is also now growing cover crops based mainly on fodder rape and leafy turnip and much of this is then sold for grazing. This is unquestionably good for the land but only time will tell as to how it impacts on protein content in malting barley. Some of the catch crop is grown under GLAS but he also has some other areas where he is looking at other species.

Brewery

Being a malting barley grower with a big interest in brewing, David has now moved to establish his own brewery in the traditional farm buildings. His Ballykilcavan Brewery brand is an effort to give the farm viability into the future. All the grains involved will be grown on the farm, malted in Athy and brewed in Ballykilcavan.

David has also acted to attempt to minimise price risk through forward-selling. He has been doing this since 2012 and, with the exception of the first year, he has recorded a price benefit relative to harvest price in all subsequent years. His price benefit ranged from €15 to €20/t and he reckoned that forward selling has earned him an additional €30,000 farm income in the past four years.

Most growers were introduced to forward selling in 2012. In the early part of that year, prices were quite reasonable, with wheat around €190/t. However, prices rose considerably closer to harvest and a bad growing year produced very poor quality, leaving many of the contracts unable to meet the quality spec with associated consequences. This experience gave forward selling a bad name for most growers and there has been very little forward selling since that year.

At the conference, I showed in graph format (Figure 2) the movement in spot wheat prices since 2010. Spot is the price available to a grower with grain in stock on the day of sale and assumes use with a short period. This graph shows significant price movement over the years and it also shows that high prices normally cure high prices.

The high prices in 2010 and 2012 were quickly followed by a significant drop to the following harvest. It is noteworthy that in the following years price bottomed out at around €190/t. But in the next three years (2014-2016) spot wheat price levels fell further due to the continuous oversupply situation and the building of global stocks.

I also looked at the forward prices that were available for November delivery in different years. Price movement in 2012 showed that no forward sale would offer a price benefit because of the rapid price rise prior to harvest. This experience, plus the issues with spec, has been a major factor in discouraging growers to sell forward in subsequent years. Most forward business on wheat was done at €190-€195/t but dry harvest price exceeded €260/t. Who would be happy to get €190/t today?

The spot price in 2012 (Figure 2) indicated the probability of a fall in 2013 and the forward prices on offer reflected that. Prices fell right up to harvest 2013 and by mid-June forward selling would have added at least €20/t on average to those sales. And that was relative to a harvest equivalent dry price of over €190/t.

In 2014, all prices rose between February and May but then fell to around €170/t for dry wheat at harvest. The result was that forward sales in January added about €13/t over harvest price but then averaged over €30/t between February and May. Even in 2015, when most growers had excellent yields and harvest price was around €165/t, forward selling could have added between €7 and €25/t right up to August.

For this reason, forward selling must be seriously considered by professional growers, either green or dry. With current surplus levels being so high, growers need to watch the market for spikes driven by things that change sentiment in the short term, as these might provide a forward selling opportunity to help increase average selling price.

It’s all about the average price whether it rises or falls after you sell.

While price is ultimately influenced by supply and demand, many other factors can influence sentiment to alter the the daily or hourly price.

Traders are influenced by reports of planting intentions, weather post establishment, snow cover, frost kill, dryness issues, political decisions, currency and especially drought. Any of these things can influence forward prices for an hour, a day or a week but then oversupply dominates again. But such reaction can provide a spike in prices that makes a sale worthwhile and it is up to each individual to know about, and avail of, such opportunities.

Grain consumption

The world has just had four-in-a-row record big harvests. While total grain consumption has increased over the years it has not been able to keep pace with production over the past four years and stocks are increasing. These stocks will help lessen the impact of any shortfall in production, should one occur in 2017, and so the prospects for any significant increase in prices must be regarded as low for the moment.

However, this could change as climatic factors in particular are bound to impact on production capability at some time. But it is also possible that we could be the victim of a low yield year and so we must always aim to keep production costs as low as possible.

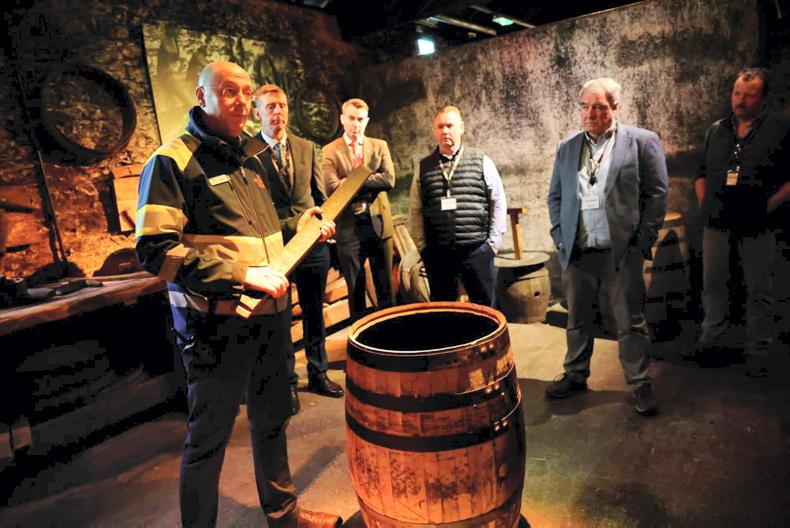

Could Irish-grown wheat be used to displace imported maize in Irish whiskey production?

This was the question behind the title of the paper presented by Sarah Clarke of ADAS. While Sarah was speaking about wheat for industrial alcohol or bioethanol production, the principles behind her presentation could equally apply to beverage production.

Sarah explained that around 2m tonnes of wheat is currently being used in Britain for bioethanol production for fuel use.

There are some but relatively few differences between bioethanol and spirit production and alcohol yield is a major factor in its competitiveness.

Sarah explained that wheat for distilling needs to be as high as possible in starch content and be as low as possible in protein content.

In most regards, this is the exact picture of Irish wheat. Sarah explained how low protein content helped to increased alcohol yield per tonne but the baseline level for her research was about 11%, a level that would be virtually impossible to achieve in an Irish winter wheat. Irish wheat is generally closer to 9.5% protein.

Starch

Average British wheat tends to have an alcohol yield of about 435 litres per tonne. Maize alcohol yield is generally regarded as being about 20 l/t higher than wheat but we need to ascertain what the alcohol yield of a 9.5% protein wheat would be.

It seems possible that good Irish wheat could well have a similar alcohol yield to imported maize which is likely to cost our distilling sector considerably more than native wheat.

Variety also matters to alcohol yield, Sarah said. Research has shown that soft endosperm wheat varieties tend to have higher alcohol yield per tonne but there are variety differences in this regard. However, simple evaluation might well provide a good indication of the potential alcohol production capacity of current and new varieties to be grown here.

Sarah also commented that triticale was assessed as a source of starch for alcohol. Laboratory tests indicated that its alcohol yield might be slightly lower than suitable wheat but it was still deemed to be a suitable source.

Expanding break-crop market

Ireland used very little break crop in its total tillage area. While this issue has been addressed at recent tillage conferences the area sown to break crops is not expanding.

Break crops can bring many advantages to an overall rotation through having a disease or pest break, possibly contributing to soil fertility and generally adding to soil structure improvements. But the crop itself may not always add directly to improved economics.

Speaking at the conference Dermot Forristal addressed these issues and showed that it is important to value the crop within the rotation.

Based on figures from previous experiments, adjusted to current prices, Dermot showed that a continuous wheat rotation averaged €36/ha profit compared to €212/ha for a winter wheat, winter barley, oilseed rape, winter barley and beans rotation.

This compared with €187/ha from a winter wheat, winter barley, oilseed, winter wheat and winter oats rotation.

While the rotation with beans is benefiting from the protein aid, Dermot said that the average profit would be somewhat lower but the benefit to the following wheat would still be there and be substantial.

While bean area has increased to utilise all of the area support, Dermot said that the utilisation of the crop at processor level is slower and has led to stocks.

He emphasised that marketing must be a coordinated approach involving everyone along the supply chain. There are real issues that need to be addressed before the sector can move on but there is a potential market size for over 400,000 tonnes in a well-developed market, even at a limited 10% inclusion rate in rations.

While there are some nutritional issues with beans, Dermot suggested that one of the main blockages to use is because there is little or no value placed on home grown traceable feed.

There is also potential to consider the human food market for this crop but this would involve exports and would have to be carefully managed and developed.

Oilseed rape is the other combinable break crop with potential to expand if there was a more sophisticated structure to the market. Over 80% of the current crop goes for animal feed with less than 10% going for cold-pressed food grade oil. And there is a somewhat similar amount used for niche markets.

While animal feed will continue to be an important part of the market the option to pursue higher value cold pressed oil markets, possibly even for the export markets, must be considered. This needs production and marketing support but it would benefit from having a potential unique selling point. He asked if there was potential in having an export brand to underpin individual brands to help do this.

A new guide to the growing, feeding, quality and purchasing arrangements for maize was launched at the conference.

This is a lovely publication directed at growers and users to help inform them of the husbandry requirements of growing the crop to help secure high output from this relatively expensive crop.

Kevin Cunningham of DLG chaired the group which produced the guide and he presented a brief description of its contents at the conference.

The section on growing introduces a new and simple method to guide growers as to the potential suitability of each of the varieties on the recommended list for planting in excellent, good or marginal sites.

Kevin emphasised that it is very difficult to get varieties that will produce their stated benefits every year and that only such varieties are recommended by the Department.

The feeding section deals with maize silage as a buffer feed, its use for indoor feeding of dairy cattle and its use in beef production systems. For maize to be useful on any farm it must contribute to farm performance, Kevin said.

Understanding quality in maize is a very important issue. Maize grown under plastic cover has higher and more consistent yield and starch levels. But achieving target dry matter and starch levels can be undone if the correct variety is not selected for specific sites.

Kevin made the interesting comment that maize quality is relatively consistent when the correct varieties are chosen for any site. Alternatively, the wrong variety can carry a penalty on farm performance.

A section of the new guide deals with the necessity for and benefits of a written contract where a grower and user are involved. Indeed, the guide contains an actual contract based on a base of 25% dry matter and 25% starch.

A third party is involved in such a contract and he/she can alter the actual price based on the actual quality in the delivered silage. So both parties are protected.

Kevin concluded by saying that maize does not suit every farm but this guide should certainly help protect both parties where the crop is to be grown on contract.

In summary

Every farm needs to continually evolve towards its future.There has been significant benefit from forward selling in most recent years.It may be possible to identify wheat varieties that are highly suitable for use in distilling.The industry needs to develop a coordinated approach to expand markets for protein crops and oilseed rape.

SHARING OPTIONS