Irish beef exports to China have been suspended again following the discovery of an atypical BSE case in a 15-year-old cow as part of routine surveillance of fallen animals at knackeries. Atypical BSE is a completely random disease in older cattle and differs from the version of the disease that was relatively common twenty years ago caused by contaminated animal feed and now eradicated.

This is the third time that beef exports to China have been disrupted because of BSE since approval was originally secured in 2018. The suspension also applies to South Korea, but as approval had just been secured for that market, beef export trade was in its infancy.

The reason for the suspension is because it is part of the Chinese import protocol for beef that all supplying countries have to comply with. Ireland hasn’t been alone in having beef exports suspended because of an isolated BSE case, the same has also happened to Brazil on two occasions.

Import protocol

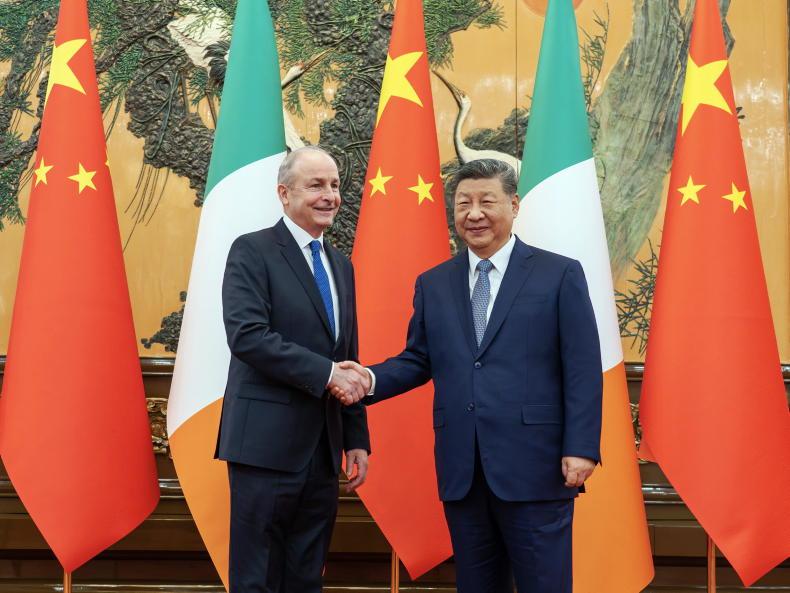

Any decision on a resumption of beef exports will be made by the Chinese authorities, with whom Irish officials will no doubt be working to address any concerns raised.

The first suspension was back in May 2020, remaining in place until the beginning of 2023. The second in November 2023, but was lifted within weeks in January this year. Irish exporters will be hoping that given the similarity of these occurrences, a quick decision will be made by China’s authorities to resume beef imports from Ireland.

Brazil’s beef exports to China were suspended between September and December 2021 and again on 23 February 2023, resuming a month later.

While Ireland and Brazil have had the same problem with atypical BSE, the trading relationship is much different because China accounts for almost half of all Brazilian beef exports, and these represent almost half of all China’s beef imports.

Brazil has been attempting to persuade China to amend its import protocol to remove the requirement of export suspension with the discovery of an atypical case of BSE. This remains a work in progress but should they succeed, Irish farmers and beef exporters are hoping that the same principle would also be extended to include Irish beef.

Why Irish exports have struggled

As Figure 1 shows, after a promising start to Irish beef exports up to the suspension in May 2020, it has been a struggle since the resumption in January 2023. While the market in China for imported beef is still growing, it is at a much slower pace than was the case up to 2021, at which point the US re-entered the market.

Table 1 shows that most of China’s beef imports come from just six countries, with Brazil being the largest supplier by a considerable distance.

With the exception of the US at present, all of these countries are much lower cost producers than Ireland.

China has also been paying much less for beef over the past two years. In 2022, Brazil’s average export price to China was $6,420 (€5,836) per tonne and in 2024 the average price has fallen to $4,430 (€4,027) per tonne, a lower value than in 2020.

The fact that demand for beef in the UK and EU, Ireland’s main export markets, has been particularly strong this year means that there is less interest in markets further afield. A restricted specification for exports to China which excludes bone in beef, offal and beef from cattle over thirty months further reduced the attraction of the Chinese market for Irish beef exporters.

No impact on cattle price

It is somewhat ironic that by having so little beef export business with China, there will be negligible disruption to the beef trade because of the suspension. At just 1,449 tonnes of beef exports to China this year out of a total of 284,000 tonnes, the volume is too small to have any real impact on the value of Irish beef in the wider marketplace.

If Brazil’s beef exports to China were suspended for a prolonged period, the impact on Irish beef prices would actually be greater than for the suspension of Irish exports. This is because China has imported 817,218 tonnes of Brazilian beef so far this year. If this volume was looking for a different market, the UK and EU would be an obvious alternative, which would put Brazil in direct competition with Irish beef exports.

Dairy and pig meat

While beef exports are small, Figure 2 shows that China remains a significant export market for Irish dairy and pigmeat, even though it has fallen in recent years. For the first seven months of this year, Irish dairy volumes were just over 36,000 tonnes. This is slightly down on last year, but considerably lower than the 62,647 tonnes in the same period in 2020.

Infant formula, which underpinned dairy exports to China for much of the past decade, has had the biggest decline over the past five years, down from 28,369 tonnes between January and July 2020 to 10,342 tonnes in the same period this year – a fall of 18,000 tonnes.

This reflects the falling birthrate in China combined with increased domestic production. Also, the volume of skimmed milk powder, which accounted for over 10,000 tonnes between January and July 2020, has collapsed to just over 400 tonnes in the first seven months of 2024.

Irish pigmeat export volumes to China peaked in 2021 at 65,141 tonnes, driven by the slump in China’s domestic production because of African swine fever, which decimated the Chinese pig herd.

This has subsequently been rebuilt with a corresponding reduction on import dependence. As a result, Irish pigmeat export volumes have fallen back to 33,104 tonnes up to July this year. Despite the large fall, China remains the largest volume export market though the UK is the top market by value due to the fact that China buys low value cuts, whereas the UK is a market for the high value cuts of pigmeat.

SHARING OPTIONS