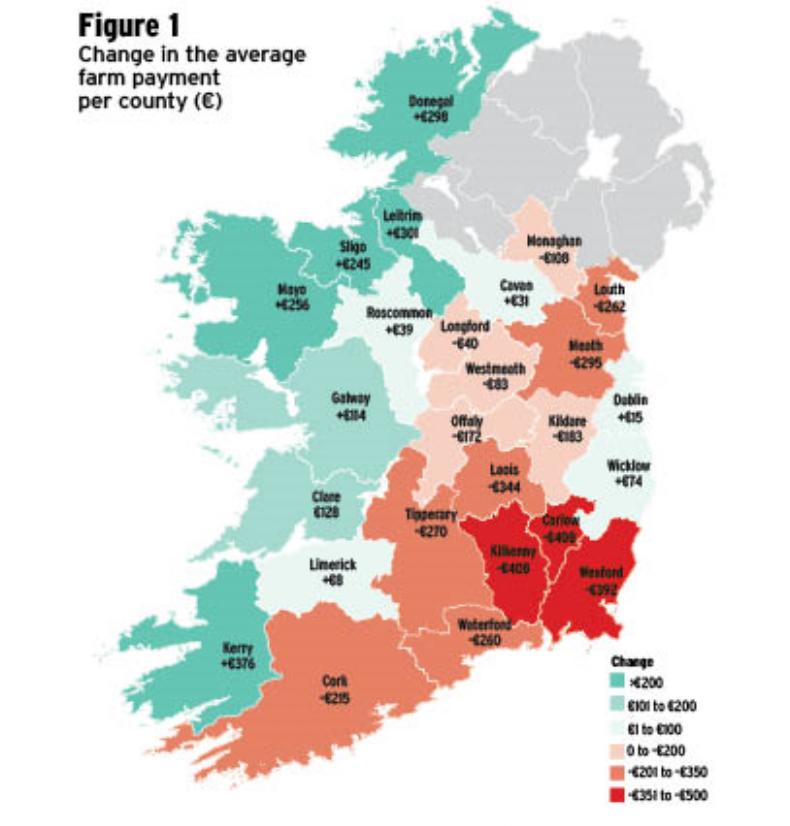

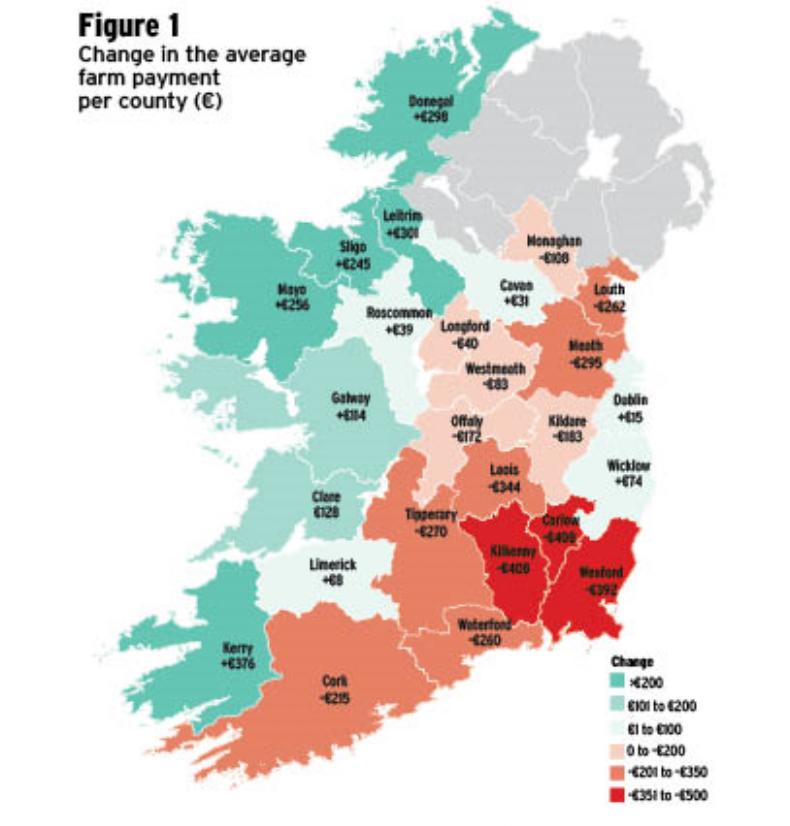

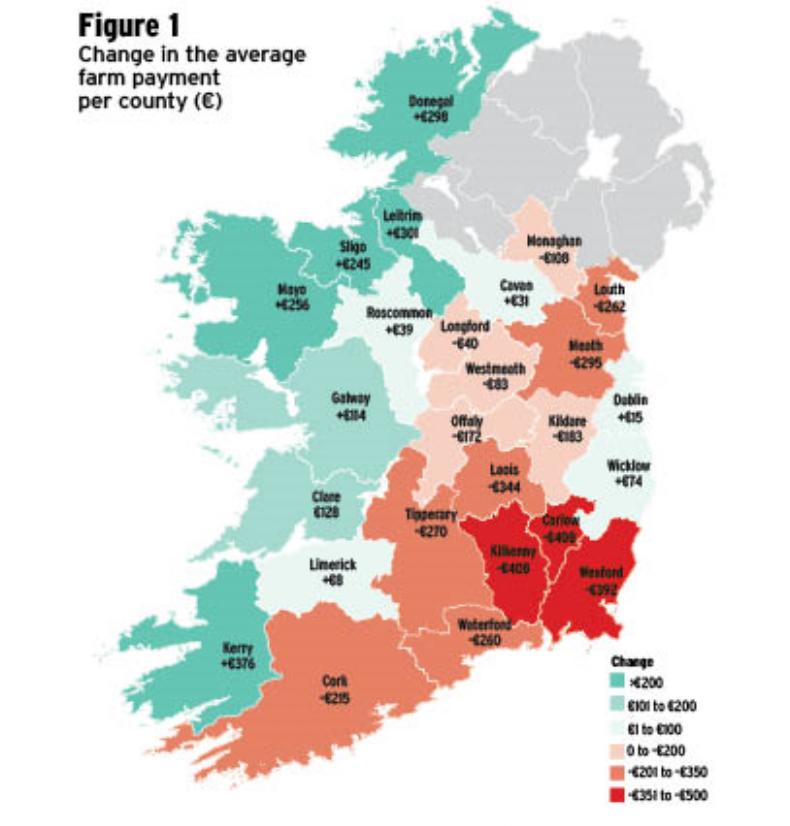

Eco-schemes are set to deliver an extra €14m in farm payments to western counties, at the expense of those in the south and east.

Eco-scheme payments will not be linked to each farmer’s existing entitlement values and will instead be paid at a flat rate when they are introduced in 2023.

This will result in farmers whose entitlements are above the current national average of €263/ha losing out as eco-schemes accelerate convergence in the next CAP.

Between 20% and 30% of Ireland’s €1.2bn direct payment budget will be set aside annually to fund eco-schemes. Once the final percentage is decided in Brussels, this portion of farmers’ direct payments will be docked to create a ring-fenced fund.

It will mean between €232m and €348m will be tied up annually to finance environmental, climate or animal welfare-related measures.

Creating this fund will see farm entitlements slashed across the country, Irish Farmers Journal analysis of Department of Agriculture figures show. Even if the lowest possible amount of 20% is ring-fenced, the average Irish farm payment of €9,467 will be cut by almost €2,000. Farmers in Cork will contribute the most (€30m) followed by Tipperary (€17.5m), Galway (€17m), and Mayo (€14.5m).

However there are farmers across the country, predominantly in western counties, that stand to gain from eco-schemes.

Mayo

Taking Mayo as an example, the 334,000 farmers in the county receive direct payments worth €73m annually, with the average entitlement value standing at €220/ha.

If it is decided in Brussels that 20% of the direct payment budget should be ring-fenced for eco-schemes, the average entitlement in Co Mayo will be reduced by €44/ha to €176/ha.

A ring-fenced fund of €232m for eco-schemes would equate to a flat-rate payment of €53/ha, with approximately 4.4m hectares eligible for payments in Ireland.

A farmer who enters an eco-scheme would see his or her entitlement increase from its original €220/ha to €228/ha.

The majority of farmers in Mayo will benefit from flat-rate eco-schemes because they have entitlements worth less than the national average.

It will increase the average payment per farm in the county from €6,492 to €6,748.

Within each county, there will be individual farmers with entitlements above and below the county average and the national average. This will determine what effect eco-schemes have on their payment.

Wexford

In Wexford, the opposite will occur. The 174,000 farmers in the southeast corner of Ireland draw down €53.5m in direct payments with the average entitlement valued at €307/ha.

Ring-fencing 20% to fund eco-schemes cuts this by €61/ha to €246/ha.

Farmers in Wexford can only apply for the same flat-rate payment of €53/ha under eco-schemes, despite contributing significantly more per hectare.

Those who secure the eco-scheme payment will have a new average entitlement value of €298/ha, a €9 reduction on the original average.

The average farm payment will be reduced by almost €400 to €13,111.

Within each county, there will be individual farmers with entitlements above and below the county average and the national average.

While averages provide a guide as to the general trend in each county, a farmer’s entitlements will determine what effect eco-schemes have on their payment.

Comment:

Why eco-schemes will make or break the next CAP

Eco-schemes are a new entry to the ever growing list of CAP jargon but their importance in the next CAP cannot be understated.

The Irish Farmers Journal analysis not only highlights their potential to accelerate convergence but also to erode a farm’s payment if the farmer does not recoup any of the ring-fenced funds.

The current average national entitlement value is €263/ha. This will fall to at least €210/ha and maybe as low as €184/ha to harvest funds for eco-schemes.

The national average payment per farm will be cut from €9,500 to at least €7,500.

The ring-fenced funds will be set aside for a flat-rate environmental payment that falls somewhere between €53/ha and €79/ha.

However, farmers are not guaranteed this payment.

Farmers must choose to take part in eco-schemes. If they do not, or if they fail to meet the requirements of the scheme, it will leave a substantial hole in their payment.

What these schemes will look like and what measures will be on offer to farmers have not yet been decided. This is where a great unknown currently exists.

It is likely that they will be closer to GLAS measures which require action on a farmer’s behalf rather than Greening requirements, which most farmers met by default.

At present, only 50,000-odd farmers out of the 123,000 who claim a direct payment have chosen to participate in voluntary agri-environmental schemes.

If the other 73,000 farmers do not sign up for eco-schemes, then there is a risk that up to €200m of direct payment money could return to Brussels unspent.

What we know about eco-schemes so far

Eco-schemes will replace Greening in the next CAP but will not be linked to existing entitlement values.Brussels will decide in the coming months what percentage of member states’ direct payments are ring-fenced for these funds – between 20% and 30%.The funds will be ring-fenced for farmers who complete actions related to climate, environment or animal welfare.It will be optional for farmers to take part but those who do not will not receive their full direct payment.Possible measures to receive payment floated in Brussels include carbon farming, eg rewetting; precision farming, eg nutrient management plans; high nature value farming, eg creating semi-natural wildflower meadows; organic farming and agro-ecology, eg multi-species swards.

Eco-schemes are set to deliver an extra €14m in farm payments to western counties, at the expense of those in the south and east.

Eco-scheme payments will not be linked to each farmer’s existing entitlement values and will instead be paid at a flat rate when they are introduced in 2023.

This will result in farmers whose entitlements are above the current national average of €263/ha losing out as eco-schemes accelerate convergence in the next CAP.

Between 20% and 30% of Ireland’s €1.2bn direct payment budget will be set aside annually to fund eco-schemes. Once the final percentage is decided in Brussels, this portion of farmers’ direct payments will be docked to create a ring-fenced fund.

It will mean between €232m and €348m will be tied up annually to finance environmental, climate or animal welfare-related measures.

Creating this fund will see farm entitlements slashed across the country, Irish Farmers Journal analysis of Department of Agriculture figures show. Even if the lowest possible amount of 20% is ring-fenced, the average Irish farm payment of €9,467 will be cut by almost €2,000. Farmers in Cork will contribute the most (€30m) followed by Tipperary (€17.5m), Galway (€17m), and Mayo (€14.5m).

However there are farmers across the country, predominantly in western counties, that stand to gain from eco-schemes.

Mayo

Taking Mayo as an example, the 334,000 farmers in the county receive direct payments worth €73m annually, with the average entitlement value standing at €220/ha.

If it is decided in Brussels that 20% of the direct payment budget should be ring-fenced for eco-schemes, the average entitlement in Co Mayo will be reduced by €44/ha to €176/ha.

A ring-fenced fund of €232m for eco-schemes would equate to a flat-rate payment of €53/ha, with approximately 4.4m hectares eligible for payments in Ireland.

A farmer who enters an eco-scheme would see his or her entitlement increase from its original €220/ha to €228/ha.

The majority of farmers in Mayo will benefit from flat-rate eco-schemes because they have entitlements worth less than the national average.

It will increase the average payment per farm in the county from €6,492 to €6,748.

Within each county, there will be individual farmers with entitlements above and below the county average and the national average. This will determine what effect eco-schemes have on their payment.

Wexford

In Wexford, the opposite will occur. The 174,000 farmers in the southeast corner of Ireland draw down €53.5m in direct payments with the average entitlement valued at €307/ha.

Ring-fencing 20% to fund eco-schemes cuts this by €61/ha to €246/ha.

Farmers in Wexford can only apply for the same flat-rate payment of €53/ha under eco-schemes, despite contributing significantly more per hectare.

Those who secure the eco-scheme payment will have a new average entitlement value of €298/ha, a €9 reduction on the original average.

The average farm payment will be reduced by almost €400 to €13,111.

Within each county, there will be individual farmers with entitlements above and below the county average and the national average.

While averages provide a guide as to the general trend in each county, a farmer’s entitlements will determine what effect eco-schemes have on their payment.

Comment:

Why eco-schemes will make or break the next CAP

Eco-schemes are a new entry to the ever growing list of CAP jargon but their importance in the next CAP cannot be understated.

The Irish Farmers Journal analysis not only highlights their potential to accelerate convergence but also to erode a farm’s payment if the farmer does not recoup any of the ring-fenced funds.

The current average national entitlement value is €263/ha. This will fall to at least €210/ha and maybe as low as €184/ha to harvest funds for eco-schemes.

The national average payment per farm will be cut from €9,500 to at least €7,500.

The ring-fenced funds will be set aside for a flat-rate environmental payment that falls somewhere between €53/ha and €79/ha.

However, farmers are not guaranteed this payment.

Farmers must choose to take part in eco-schemes. If they do not, or if they fail to meet the requirements of the scheme, it will leave a substantial hole in their payment.

What these schemes will look like and what measures will be on offer to farmers have not yet been decided. This is where a great unknown currently exists.

It is likely that they will be closer to GLAS measures which require action on a farmer’s behalf rather than Greening requirements, which most farmers met by default.

At present, only 50,000-odd farmers out of the 123,000 who claim a direct payment have chosen to participate in voluntary agri-environmental schemes.

If the other 73,000 farmers do not sign up for eco-schemes, then there is a risk that up to €200m of direct payment money could return to Brussels unspent.

What we know about eco-schemes so far

Eco-schemes will replace Greening in the next CAP but will not be linked to existing entitlement values.Brussels will decide in the coming months what percentage of member states’ direct payments are ring-fenced for these funds – between 20% and 30%.The funds will be ring-fenced for farmers who complete actions related to climate, environment or animal welfare.It will be optional for farmers to take part but those who do not will not receive their full direct payment.Possible measures to receive payment floated in Brussels include carbon farming, eg rewetting; precision farming, eg nutrient management plans; high nature value farming, eg creating semi-natural wildflower meadows; organic farming and agro-ecology, eg multi-species swards.

SHARING OPTIONS