It has been a dry summer up to July, and factory reports from livers examined would suggest low fluke levels to this point in the year. August means normal rainfall has resumed and this fluke risk could increase.

Fluke risk is as usual higher as you travel to the west and north of the country. However, there can be differences between farms and in sheep farms we have the added problem of fluke resistance to products containing triclabendazole.

Looking at bulk milk testing on dairy farms, no alarm bells have been raised yet on fluke antibody levels.

Is fluke a growing problem?

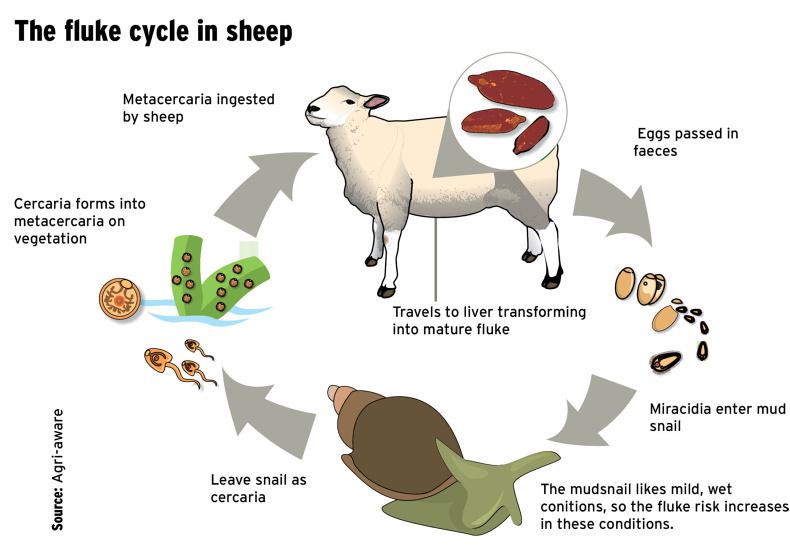

In most respects it is. Warmer weather and more winter rainfall provide the ideal conditions for the intermediate host, the mud snail population, to increase. As with all other diseases, increased animal movements on to farms greatly increases the risk. This means quarantine dosing of new arrivals becomes an essential part of a good biosecurity plan.

Identifying the risk

More farms need to embrace testing and assess their risk for fluke. Some farms will find they have no fluke and don’t need to be dosing. Others will find they need to be dosing more regularly.

Have you had fluke in previous years? If so, then fluke will continue to be a risk from year to year. We can reduce the risk by:

Breaking the cycle in spring, a dose that kills adult fluke like an albendazole.Managing drainage during the summer months and fixing leaking water pipes.Fencing off wet areas in autumn and reducing the risk to the mudsnail or intermediate host.Using strategic dosing at winter housing.Firstly, we need to be mindful of severe clinical signs. If you notice poor performance in older/mature animals in the autumn, always ask if fluke is involved.

The factory reports on any cattle submitted for slaughter provide valuable information around liver fluke. If liver fluke are observed, a dosing plan needs to move forward quickly, while chronic damage means an overall control plan might be necessary.

Dung samples for fluke eggs are OK but require adult fluke to be present, meaning we have the chance of missing the early life cycle stages of immature fluke and early immature fluke. Both of these stages can damage the liver while travelling through it over 12 to 14 weeks.

A faecal coproantigen test can now be carried out which gives an earlier indication without the need for eggs in the dung.

Also more vets are using blood testing in young animals to measure antibody levels which gives a good indicator of exposure to fluke before housing time.

Dairy farmers should really be utilising their bulk milk samples to check for antibody levels which again will show if exposure to liver fluke at herd level is an issue. Although not ideal, even one bulk milk fluke reading in October is useful. Remember, high readings will last for three months and all this information must be used with any other farm history.

Any animals that die on farm need to have post-mortems carried out and particular attention should be paid to livers. This is particularly true for sheep that die suddenly on farm. Sheep are more prone to acute fluke (death) while in cattle it tends to be a chronic problem (lost performance).

What can fluke infections mean?

The extreme of fluke infections means sick animals with bottle jaw (soft swelling under the jaw), weakness, anaemina and with sheep sudden death.

Subclinical issues which can severely affect your production and individual animal’s immunity are more common. I saw a case last month in dairy cows where pneumonia in cows was most likely being caused by underlying fluke issues on the farm.

It is vital that any sheep that die on farm over the coming months have post-mortems carried out and livers checked for any evidence for fluke.

In cattle herds there often are more issues with salmonella abortions and scours when you have fluke issues. Sheep are also more at risk of sudden death from clostridial diseases.

Starting a treatment plan

Any animals with severe or heavy fluke infestations need to be monitored closely after treatment. At herd level the key steps are to:

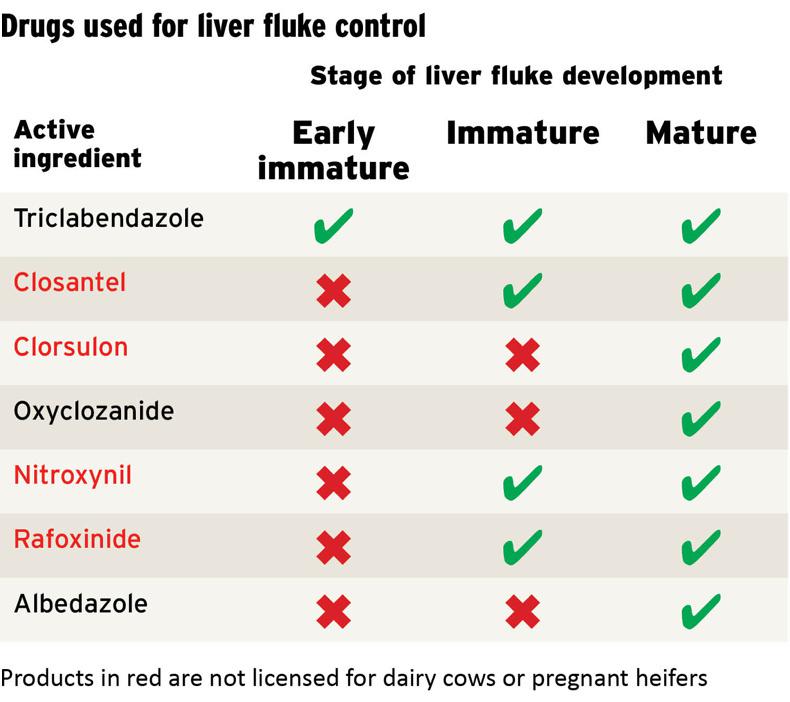

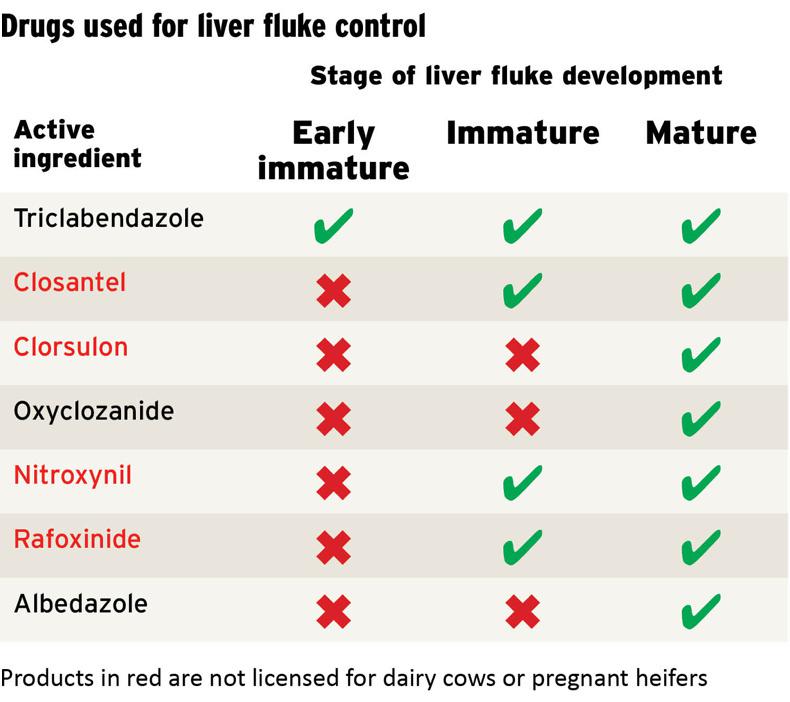

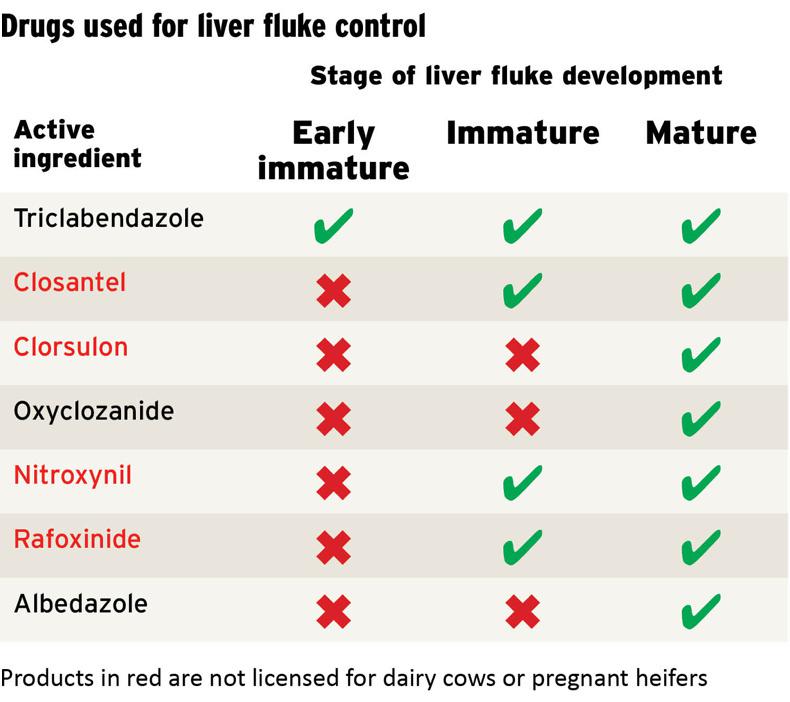

See if the product is licensed for use.Check appropriate withdrawals.Check what stage of the life cycle it treats and if it’s the right product for the time of year.Administer the right amount by the correct route.Do faecal egg counts four weeks after dosing to check resistance.Work with your vet to develop a farm-specific control planTriclabendazole resistance

If you’re using a triclabendazole product, it is advised particularly in sheep to take some faecal samples three to four weeks after dosing to check for any fluke eggs. Also it is very important for any sheep farmers to be wary of buying in fluke resistance in animals into your flock.

This is the fourth year of a study on fluke antibodies in lambs at slaughter, when bloods taken from lambs are checked for fluke exposure.

Starting with 2,000 lambs in 2015 they have now tested close to 6000 lambs this year. Antibodies are created if the lamb’s immune system is in contact with the liver fluke parasite. By checking county of origin, the Department can now track levels of fluke risk across the national flock. Although there will be variances across farms, this approach is another piece of the jigsaw for fluke surveillance. The north and the west have seen levels increase in July, with some cases in August also in the southwest.

This information is available in the animal health and disease surveillance section of the Department’s website.

It has been a dry summer up to July, and factory reports from livers examined would suggest low fluke levels to this point in the year. August means normal rainfall has resumed and this fluke risk could increase.

Fluke risk is as usual higher as you travel to the west and north of the country. However, there can be differences between farms and in sheep farms we have the added problem of fluke resistance to products containing triclabendazole.

Looking at bulk milk testing on dairy farms, no alarm bells have been raised yet on fluke antibody levels.

Is fluke a growing problem?

In most respects it is. Warmer weather and more winter rainfall provide the ideal conditions for the intermediate host, the mud snail population, to increase. As with all other diseases, increased animal movements on to farms greatly increases the risk. This means quarantine dosing of new arrivals becomes an essential part of a good biosecurity plan.

Identifying the risk

More farms need to embrace testing and assess their risk for fluke. Some farms will find they have no fluke and don’t need to be dosing. Others will find they need to be dosing more regularly.

Have you had fluke in previous years? If so, then fluke will continue to be a risk from year to year. We can reduce the risk by:

Breaking the cycle in spring, a dose that kills adult fluke like an albendazole.Managing drainage during the summer months and fixing leaking water pipes.Fencing off wet areas in autumn and reducing the risk to the mudsnail or intermediate host.Using strategic dosing at winter housing.Firstly, we need to be mindful of severe clinical signs. If you notice poor performance in older/mature animals in the autumn, always ask if fluke is involved.

The factory reports on any cattle submitted for slaughter provide valuable information around liver fluke. If liver fluke are observed, a dosing plan needs to move forward quickly, while chronic damage means an overall control plan might be necessary.

Dung samples for fluke eggs are OK but require adult fluke to be present, meaning we have the chance of missing the early life cycle stages of immature fluke and early immature fluke. Both of these stages can damage the liver while travelling through it over 12 to 14 weeks.

A faecal coproantigen test can now be carried out which gives an earlier indication without the need for eggs in the dung.

Also more vets are using blood testing in young animals to measure antibody levels which gives a good indicator of exposure to fluke before housing time.

Dairy farmers should really be utilising their bulk milk samples to check for antibody levels which again will show if exposure to liver fluke at herd level is an issue. Although not ideal, even one bulk milk fluke reading in October is useful. Remember, high readings will last for three months and all this information must be used with any other farm history.

Any animals that die on farm need to have post-mortems carried out and particular attention should be paid to livers. This is particularly true for sheep that die suddenly on farm. Sheep are more prone to acute fluke (death) while in cattle it tends to be a chronic problem (lost performance).

What can fluke infections mean?

The extreme of fluke infections means sick animals with bottle jaw (soft swelling under the jaw), weakness, anaemina and with sheep sudden death.

Subclinical issues which can severely affect your production and individual animal’s immunity are more common. I saw a case last month in dairy cows where pneumonia in cows was most likely being caused by underlying fluke issues on the farm.

It is vital that any sheep that die on farm over the coming months have post-mortems carried out and livers checked for any evidence for fluke.

In cattle herds there often are more issues with salmonella abortions and scours when you have fluke issues. Sheep are also more at risk of sudden death from clostridial diseases.

Starting a treatment plan

Any animals with severe or heavy fluke infestations need to be monitored closely after treatment. At herd level the key steps are to:

See if the product is licensed for use.Check appropriate withdrawals.Check what stage of the life cycle it treats and if it’s the right product for the time of year.Administer the right amount by the correct route.Do faecal egg counts four weeks after dosing to check resistance.Work with your vet to develop a farm-specific control planTriclabendazole resistance

If you’re using a triclabendazole product, it is advised particularly in sheep to take some faecal samples three to four weeks after dosing to check for any fluke eggs. Also it is very important for any sheep farmers to be wary of buying in fluke resistance in animals into your flock.

This is the fourth year of a study on fluke antibodies in lambs at slaughter, when bloods taken from lambs are checked for fluke exposure.

Starting with 2,000 lambs in 2015 they have now tested close to 6000 lambs this year. Antibodies are created if the lamb’s immune system is in contact with the liver fluke parasite. By checking county of origin, the Department can now track levels of fluke risk across the national flock. Although there will be variances across farms, this approach is another piece of the jigsaw for fluke surveillance. The north and the west have seen levels increase in July, with some cases in August also in the southwest.

This information is available in the animal health and disease surveillance section of the Department’s website.

SHARING OPTIONS