This week, almost 50% are calved as the first three weeks of autumn calving is completed. The rest will calve between now and end of November.

Previously, the trial at Johnstown was 100% autumn calving but the researchers involved decided to change to spring and autumn calving to better reflect the calving pattern at national level.

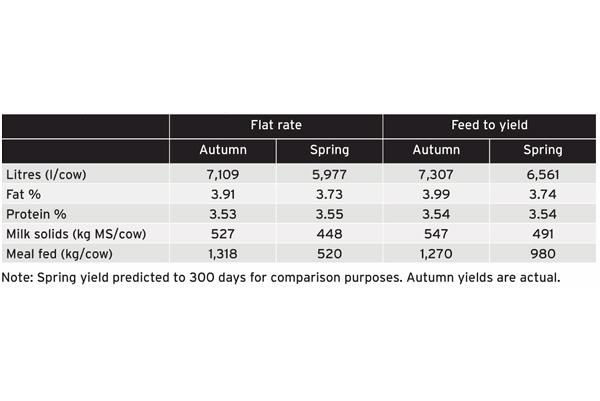

There are 100 cows, split 50/50, on a feeding trial comparing ‘flat rate’ with ‘feed to yield’ feeding system. About 60 cows calf in the spring and 40 in the autumn.

So, this week, for the group of 50 cows on the ‘feed to yield’ trial, there are 20 spring calved cows, all still in milk, and 15 freshly calved autumn calving cows. The same applies for the ‘flat rate’ group. Current feeding management is summarised in Figure 1.

The ‘feed to yield’ group are getting 2kg of meal in the parlour (1kg in AM, 1kg in PM) while at grass day and night. Cows milking over 21kg are getting more meal depending on their yield.

The ‘flat rate’ group are getting 4kg of meal per cow and grazed grass so obviously the spring calvers are getting a lot of meal considering they are close to the end of lactation.

The winter diet plan, which will kick in from mid-November onwards, is also in Figure 1.

Essentially the cows in the ‘feed to yield’ feeding system will get only 2.5kg of meal per cow in the wagon mix, and will be fed 0.5kg for every kg of milk above 21kg in the parlour.

The cows on the ‘flat rate’ system will get up to 8kg of meal in the wagon mix. Both groups will get very good quality grass and maize silage.

Milk performance review

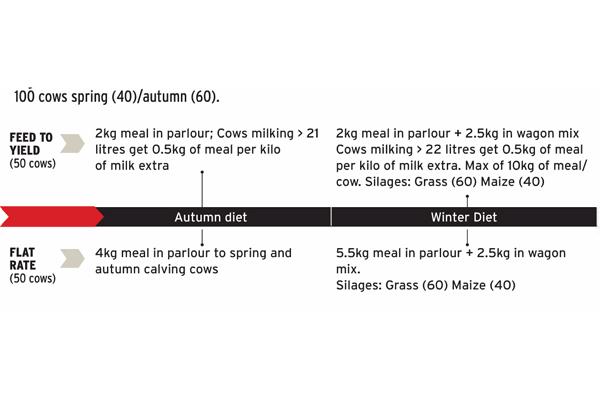

Table 1 shows the actual milk yields of the autumn calving cows that calved down this time last year and a predicted year-end figure for the spring calving cows that are coming to the end of lactation. There are a couple of messages.

||PIC2||

Joe Patton and Aidan Lawless from Teagasc stress first that high grass utilisation per hectare, excellent silage and more milk from forage are the main drivers of both systems – neither option is likely to be profitable if these fundamentals are wrong.

The Johnstown herd is producing close to 4,500 litres per cow from forage and utilised 10.8 tonnes grass per hectare last year.

The winter diet is relatively simple – a concentrate blend of barley (28), soyahulls (25), distillers (25) and soyabean meal (22) with grass silage and maize silage. Straw is not included in the diet if the NDF (fibre) of the silages are adequate for rumen health (>40 for NDF).

Comparisons

Maximum use of grazed grass is the aim from February to November.

If you look at just the two autumn calving groups, you can see the ‘flat rate’ group produced 527kg of milk solids per cow for a meal input of 1,318kg/cow.

||PIC3||

The ‘feed to yield’ group produced 547kg of milk solids for slightly less meal. Total meal fed was 20% above target in both cases due to grass shortages in spring, but there is evidence of less efficient use of concentrate with flat rate feeding.

In Johnstown Castle, the ‘feed to yield’ system is driven by computerised feeding but, if you don’t have this system, you could still operate a ‘feed to yield’ system similar to what Fran Allen is proposing on Pages 2 and 3 of this supplement.

Comparing the predicted yields of the two spring calving groups, the ‘feed to yield’ group are producing close to 600 litres more milk per cow (50kg MS) for an extra 460kg of meal.

The response to additional meal (1.3 litres for 1kg of meal) is better than the normal response rates (less than 1 litre per kg of meal) because feed is being targeted to those cows producing more milk at a given point in time.

Joe and Aidan emphasise that grazed grass was challenged to support the first 24 litres per cow through the summer, and extra individual feeding only occurred from that point upward.

Grass most important

So the message again is that growing and utilising more grass is the most important part of both feeding regimes.

Once a high level of milk output from grass is being achieved, feeding to individual cow production is more efficient than flat rate feeding. This is especially important if there is a range in stage of lactation in the herd, and may be less relevant where block calving is the norm.

On the other hand, setting out to drive extra milk yield through supplementation across the board will likely give a much poorer response in comparison.

In summary, the researchers are keen to point out feed efficiency will be improved if you keep the base diet at lower levels and target feed more in the parlour on an individual cow or group basis rather than flat rate feeding in excess of requirements.

Good quality forages are essential if producing milk during the winter and will reduce the amount of purchased concentrate required.

The Johnstown grass silages are all over 75DMD and smaller amounts of meal with good forages will produce a lot of milk cheaply for winter milk herds.

SHARING OPTIONS