The great financial crash and the near-death crisis in the eurozone from 2010 to 2012 ushered in a period of low interest rates at levels unprecedented in modern times. There has been ruin for those who had borrowed too much and defaulted, but an unexpected reprieve for those who had emerged intact. In Ireland, the State itself lost the capacity to borrow at all in the autumn of 2010, but from 2014 onwards, as the crisis unravelled, government borrowing became suddenly more affordable. Both public and private balance sheets around Europe loaded up on debt while the going was good.

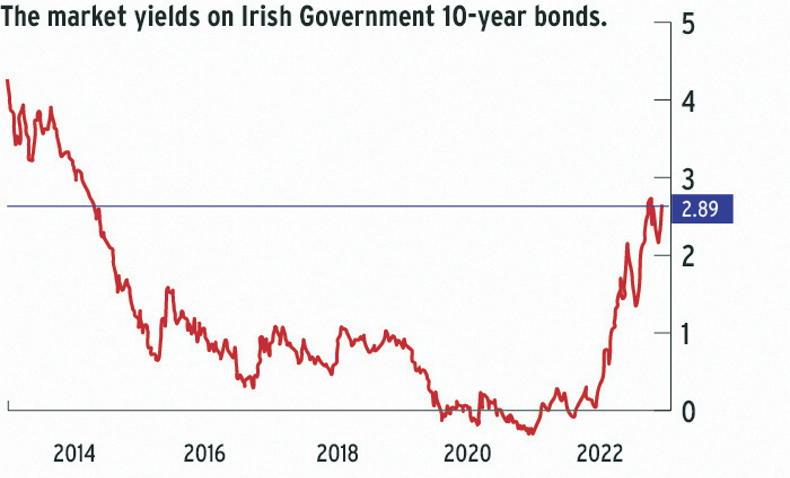

While total Irish public debt has risen to very high levels relative to the tax base, and we have one of the highest ratios in the eurozone, the cost of Government borrowing at the 10-year maturity fell all the way to zero in 2020, flattering the budget accounts. But this holiday from ultra-low interest rates is over, for governments, households and commercial borrowers.

Of the major central banks, the European Central Bank (ECB) in Frankfurt, which makes the decisions driving interest rates here in Ireland, has been slower than its peers in tightening monetary policy.

Both public and private balance sheets around Europe loaded up on debt while the going was good

The Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, is furthest along the curve and the federal funds rate, at which it deals in the wholesale market, reached 4.33% in the week before Christmas, compared to 0.08% (call it zero) 12 months earlier. Commercial bank lending rates, including mortgage rates, have followed its lead and US treasury bond yields have been just under 4% at the 10-year maturity, around 1% higher than yields in Ireland.

The 10-year maturity is often used for international comparisons, because governments try to use a mix of short- and long-dated government debt whose maturity averages out at around the 10-year mark.

Debt

Government debt never gets repaid – it gets re-financed with fresh debt, borrowed anew at the prevailing rate. If the prevailing rate rises, the holiday comes, gradually, to an end and the annual budget must reflect the rising debt service burden.

Ireland has a long average maturity, longer than many other countries in Europe, and only a small amount of the debt overhang needs to be re-financed in the next few years. But all has to be re-financed eventually and holidays do not endure. If the extraordinary period of low, even negative, official interest rates is truly over, the Irish public finances are not as secure as the more buoyant commentators would have you believe.

If the prevailing rate rises, the holiday comes, gradually, to an end

The declared upper bound for the Federal Reserve funds rate, for now, is 4.5%. The ECB equivalent is two points lower, at 2.5%, since the ECB has been slower in tightening monetary policy. The Bank of England, criticised for being sluggish in its response to the inflation surge, is higher than the ECB at 3.5%. All three have a formal inflation target at 2% and all intend to deliver, which means that official interest rates will rise further, and all three central banks – and most others around the world – have signalled their intentions.

The inflation will be squeezed out, through tighter monetary policy, including an end to central bank support for government bond markets. Several central banks, including the ECB, will start selling government bonds into the market, having been purchasers on a prodigious scale these last few years.

There is one circumstance in which this will not happen, namely a really deep European economic downturn

If the ECB increases the official interest rate early this year, and it has said clearly that it will, how far will it go?

Normality, with inflation at 2%, implies official interest rates at something like 4%, government bond yields and hence re-financing costs at 5-6% and commercial bank lending rates a point or two higher for well-secured loans.

There is one circumstance in which this will not happen, namely a really deep European economic downturn, which would cause the ECB to pause the path on which it has embarked. If the downturn is mild, interest rates will rise much further, including rates for households and for commercial borrowers, including farmers.

If you would prefer to believe in a happier scenario for interest rates, you had better expect a sharper economic recession. Take your pick.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: