Out of all the targets set out in the Climate Action Plan, our solar PV targets are among the few that we are genuinely optimistic about meeting.

This was a prevailing message from the recent Irish Solar Energy Association (ISEA) annual conference attended by the Irish Farmers Journal.

The conference hosted nearly 500 key figures in the Irish solar industry, and the atmosphere was undeniably electric.

After a long-awaited start, this industry is firmly in growth-mode. Until August 2022, Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) statistics showed zero per cent of Irish power came from solar.

However, this summer, solar reportedly provided up to 10% of Ireland’s electricity.

Solar is not a marginal technology; it is, in fact, a core component of Ireland’s decarbonisation toolkit, according to Conall Bolger, CEO of ISEA.

In his opening address, he reminded delegates that by 2030, we must develop eight gigawatts (GW) of solar PV. For reference, this is equivalent to roughly 40,000 acres of solar farms. Solar farms vary in size, but scale matters.

Between 2018 and 2020, most solar farms entering the planning system were between 50 and 100 acres in size. More recently, during 2021-2023, projects of over 250 acres and above have entered the planning system across the country.

Larger projects typically connect to the national grid using a 110kV or 220kV grid connection, either via an underground electrical cable to the most viable substation or by directly tying into an overhead transmission line.

First project

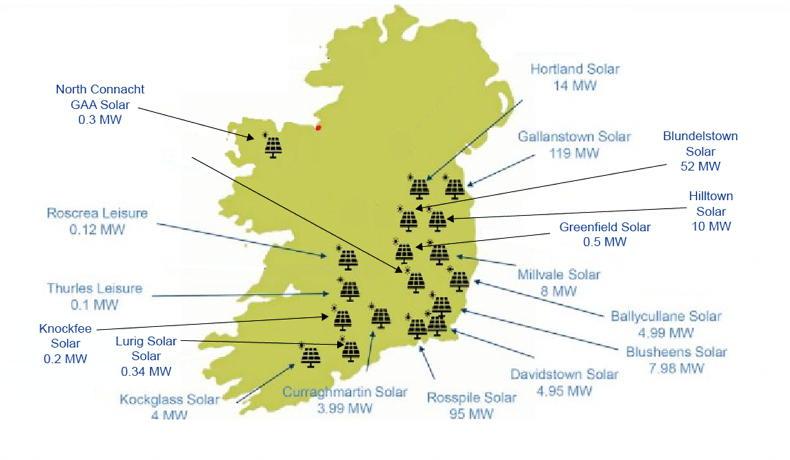

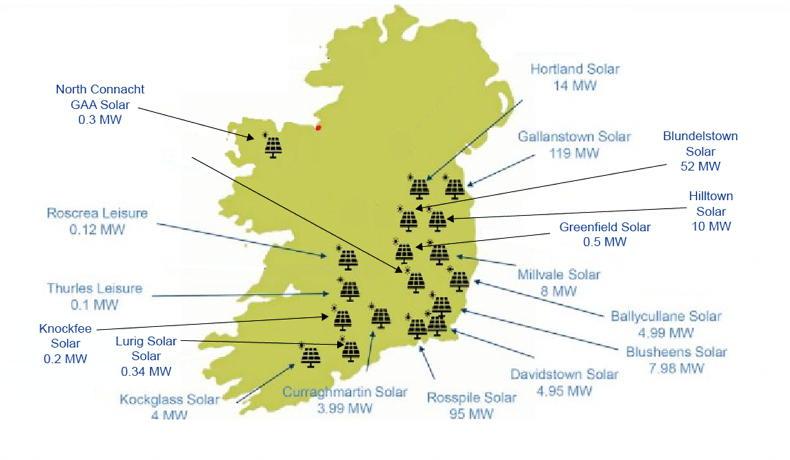

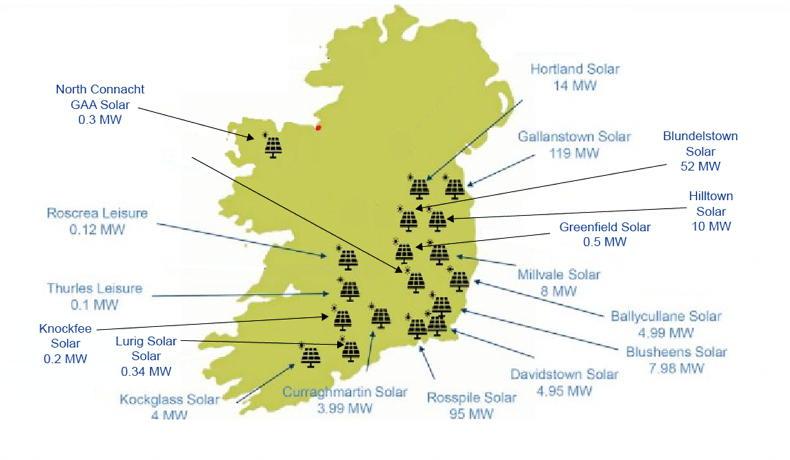

The first utility-scale project, Neoen’s Millvale Solar in Wicklow, connected to the public electricity network last summer.

The first three Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) auctions awarded 2.7GW of contracts to solar PV, equivalent to over one-third of our 2030 target. The fourth RESS auction will likely take place in 2024.

A total of 18 projects are now connected to the grid (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ESB-connected solar farms in 2022 and 2023 so far.

The microgeneration support framework has also driven a surge in solar deployment, with 700 systems registering per week at times this year. We are on track to have 300MW from microgeneration alone by the end of 2023.

Healthy pipeline

To meet the target of 8GW by 2030, we need to deliver at least one gigawatt every year from now until the end of the decade. This is achievable as, so far, 6GW of solar farms have secured planning permission, with a total of 10GW in the pipeline.

These figures exclude the new developments under the SEAI’s Non-Domestic Microgen Scheme, which will see more large-scale rooftop solar PV systems installed in businesses, as well as projects likely to emerge from the Small-Scale Renewable Electricity Support Scheme, which is due to be introduced soon.

Public acceptance of solar PV is at an all-time high. While there are notable projects that have attracted high-profile and vocal objectors, according to SEAI’s latest research, these are the minority, as the majority surveyed expressed high levels of support for the sector.

The industry has proven to be a success story for Ireland, and judging by the comments made by Minister Michael McGrath, Sean Kelly MEP and Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald, who opened the conference, support for this industry is not likely to diminish anytime soon.

Changes

However, like in any industry, there are measures that could be introduced and streamlined to significantly benefit the industry, as Bolger told attendees, forming the topic of many discussions at the conference.

Allowing private wires to enable renewable projects to connect directly to customers, as well as permitting hybrid sites (co-locating wind and solar projects on the same site, for example), would facilitate a further rollout of renewable capacity while awaiting the development of the electricity network.

He emphasised the need for “grown-up conversations” between the industry and the Government regarding delivery dates for awarded RESS contracts, showing flexibility in light of grid timelines, and collaborating on the design of future RESS auctions.

County targets

The event coincided with the publication of the ISEA’s new Best Practice Guidance Report for Large Scale Solar Energy Development, intended for both applicants and planners, offering a unified approach to help streamline and speed up the solar farm planning process. You can listen to the interview with Bolger here.

However, planning policies relating to renewable energy projects are set to change, with local authorities expected to identify suitable land areas for renewable energy development. This practice is already in place in many counties for wind energy, but is expected to extend to other renewable energy technologies.

During the morning session, Matt Collins, assistant secretary of the Department of the Environment, Climate & Communication, explained that his department is working on a new Renewable Electricity Spatial Policy Framework (RESPF).

The RESPF is a plan-led, evidence-based approach to allocating renewable electricity generation targets across the three regional assemblies: the northern and western region, the eastern and midlands region, and the southern region, as Collins stated. The regional targets will then serve as the basis for specific targets for each county.

These targets will inform the local authority renewable energy strategies (LARES), which will be given statutory basis and incorporated into county or city development plans. A central component of LARES is a spatial assessment of land areas suitable for renewable energy development of all kinds.

Laggards

Work is already underway to map out renewable acceleration areas in Ireland as directed to under the recast Renewable Energy Directive.

Ireland has been lagging in implementing EU planning policy, with only 25% of the legally mandated EU Emergency Regulation, first set out in December 2022, having been transposed into Irish law.

The new guidelines for solar farms are informative and useful, setting an example for other sectors. Similar guidelines need to be published for small-scale solar projects or even export-led rooftop systems.

However, the same type of guidance document should be developed for other technologies like anaerobic digestion and small-scale wind.

While similar reports for these technologies have been published in the past, the planning system has evolved and we need new guidelines.

The development of county-specific renewable energy targets, aligned with national targets, and the identification of suitable lands for renewable energy development could be a game-changer. However, the public, including farmers, need to have a say in this, with a clear methodology for determining land suitability.

A wind turbine is very different from a solar farm, which is very different from an anaerobic digestion plant.

Each technology will require its own methodology, with public input in determining this. This could be our farm organisation’s chance to help influence where renewable projects can be developed, as some have called for.

Listen below

Stephen Robb talks to Conall Bolger, CEO of the Irish Solar Energy Association, about the new planning guidance document for large-scale solar farms developed and launched by his organisation, and the impact this will have on solar farm developments.

Out of all the targets set out in the Climate Action Plan, our solar PV targets are among the few that we are genuinely optimistic about meeting.

This was a prevailing message from the recent Irish Solar Energy Association (ISEA) annual conference attended by the Irish Farmers Journal.

The conference hosted nearly 500 key figures in the Irish solar industry, and the atmosphere was undeniably electric.

After a long-awaited start, this industry is firmly in growth-mode. Until August 2022, Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) statistics showed zero per cent of Irish power came from solar.

However, this summer, solar reportedly provided up to 10% of Ireland’s electricity.

Solar is not a marginal technology; it is, in fact, a core component of Ireland’s decarbonisation toolkit, according to Conall Bolger, CEO of ISEA.

In his opening address, he reminded delegates that by 2030, we must develop eight gigawatts (GW) of solar PV. For reference, this is equivalent to roughly 40,000 acres of solar farms. Solar farms vary in size, but scale matters.

Between 2018 and 2020, most solar farms entering the planning system were between 50 and 100 acres in size. More recently, during 2021-2023, projects of over 250 acres and above have entered the planning system across the country.

Larger projects typically connect to the national grid using a 110kV or 220kV grid connection, either via an underground electrical cable to the most viable substation or by directly tying into an overhead transmission line.

First project

The first utility-scale project, Neoen’s Millvale Solar in Wicklow, connected to the public electricity network last summer.

The first three Renewable Electricity Support Scheme (RESS) auctions awarded 2.7GW of contracts to solar PV, equivalent to over one-third of our 2030 target. The fourth RESS auction will likely take place in 2024.

A total of 18 projects are now connected to the grid (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: ESB-connected solar farms in 2022 and 2023 so far.

The microgeneration support framework has also driven a surge in solar deployment, with 700 systems registering per week at times this year. We are on track to have 300MW from microgeneration alone by the end of 2023.

Healthy pipeline

To meet the target of 8GW by 2030, we need to deliver at least one gigawatt every year from now until the end of the decade. This is achievable as, so far, 6GW of solar farms have secured planning permission, with a total of 10GW in the pipeline.

These figures exclude the new developments under the SEAI’s Non-Domestic Microgen Scheme, which will see more large-scale rooftop solar PV systems installed in businesses, as well as projects likely to emerge from the Small-Scale Renewable Electricity Support Scheme, which is due to be introduced soon.

Public acceptance of solar PV is at an all-time high. While there are notable projects that have attracted high-profile and vocal objectors, according to SEAI’s latest research, these are the minority, as the majority surveyed expressed high levels of support for the sector.

The industry has proven to be a success story for Ireland, and judging by the comments made by Minister Michael McGrath, Sean Kelly MEP and Sinn Féin leader Mary Lou McDonald, who opened the conference, support for this industry is not likely to diminish anytime soon.

Changes

However, like in any industry, there are measures that could be introduced and streamlined to significantly benefit the industry, as Bolger told attendees, forming the topic of many discussions at the conference.

Allowing private wires to enable renewable projects to connect directly to customers, as well as permitting hybrid sites (co-locating wind and solar projects on the same site, for example), would facilitate a further rollout of renewable capacity while awaiting the development of the electricity network.

He emphasised the need for “grown-up conversations” between the industry and the Government regarding delivery dates for awarded RESS contracts, showing flexibility in light of grid timelines, and collaborating on the design of future RESS auctions.

County targets

The event coincided with the publication of the ISEA’s new Best Practice Guidance Report for Large Scale Solar Energy Development, intended for both applicants and planners, offering a unified approach to help streamline and speed up the solar farm planning process. You can listen to the interview with Bolger here.

However, planning policies relating to renewable energy projects are set to change, with local authorities expected to identify suitable land areas for renewable energy development. This practice is already in place in many counties for wind energy, but is expected to extend to other renewable energy technologies.

During the morning session, Matt Collins, assistant secretary of the Department of the Environment, Climate & Communication, explained that his department is working on a new Renewable Electricity Spatial Policy Framework (RESPF).

The RESPF is a plan-led, evidence-based approach to allocating renewable electricity generation targets across the three regional assemblies: the northern and western region, the eastern and midlands region, and the southern region, as Collins stated. The regional targets will then serve as the basis for specific targets for each county.

These targets will inform the local authority renewable energy strategies (LARES), which will be given statutory basis and incorporated into county or city development plans. A central component of LARES is a spatial assessment of land areas suitable for renewable energy development of all kinds.

Laggards

Work is already underway to map out renewable acceleration areas in Ireland as directed to under the recast Renewable Energy Directive.

Ireland has been lagging in implementing EU planning policy, with only 25% of the legally mandated EU Emergency Regulation, first set out in December 2022, having been transposed into Irish law.

The new guidelines for solar farms are informative and useful, setting an example for other sectors. Similar guidelines need to be published for small-scale solar projects or even export-led rooftop systems.

However, the same type of guidance document should be developed for other technologies like anaerobic digestion and small-scale wind.

While similar reports for these technologies have been published in the past, the planning system has evolved and we need new guidelines.

The development of county-specific renewable energy targets, aligned with national targets, and the identification of suitable lands for renewable energy development could be a game-changer. However, the public, including farmers, need to have a say in this, with a clear methodology for determining land suitability.

A wind turbine is very different from a solar farm, which is very different from an anaerobic digestion plant.

Each technology will require its own methodology, with public input in determining this. This could be our farm organisation’s chance to help influence where renewable projects can be developed, as some have called for.

Listen below

Stephen Robb talks to Conall Bolger, CEO of the Irish Solar Energy Association, about the new planning guidance document for large-scale solar farms developed and launched by his organisation, and the impact this will have on solar farm developments.

SHARING OPTIONS