Achieving sustainable living is the worthy ambition of virtually every government and citizen in the world. The problem is that while society believes in living in a sustainable manner, individual exceptionalism creeps in. We continue doing as we please while looking over our shoulder and pointing out others that are doing worse. In this regard, Irish farmers are an easy target. Their number and economic importance is falling as the country’s population increases. The economy is now underpinned by the major global technological and pharmaceutical companies that have Ireland as their European and, in some cases, global headquarters.

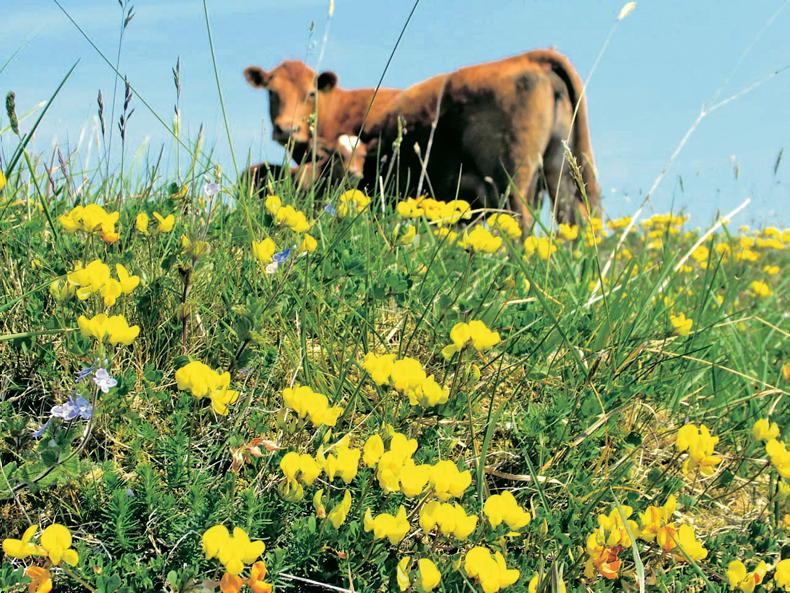

Agriculture, the livestock sector in particular, has been left carrying the can for almost 40% of Ireland’s total emissions. Of course, it isn’t fair or correct that emissions from agriculture are calculated at source rather than at the point of consumption. Ireland is penalised in this calculation by being an efficient producer of grass, with access to an abundance of water, which is converted into protein that can be used by humans through livestock farming.

If like Britain, Ireland had huge reserves of coal and iron ore, agriculture would have closer to a 10% share of national emissions, but that ultimately is neither here nor there.

Reason for agriculture being the main cause of emissions

Similarly, our Government has taken an absolutist approach to delivering a 50% cut in total emissions by 2030. So far this has had a false start, although agriculture is the only sector to deliver a reduction last year even if it was still short of its target.

This absolutist approach isn’t the case where governments have adopted a more protective role for national interests.

Therefore, we see Germany make a case for retaining the internal combustion engine run by biofuels, and the US looking to technological developments in agriculture rather than reduced production. Australia will continue mining and its strategy for agriculture envisages an AUS S100bn (€59bn) industry by 2030 – that’s a 20% increase on the sector’s current value there.

Irish agriculture has also made and lost the argument that concentrating livestock production in the most efficient grass growing parts of the world, of which Ireland is one, makes sense as it delvers the lowest amount of emissions per unit of production. Government policy in Ireland is that we deliver sectoral and national emissions reductions irrespective of the benefit to the global output.

There are different ways in which Ireland can deliver the emissions reduction targets from agriculture.

Teagasc MACC

One such route was identified in the recent update of the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve by Teagasc, commonly referred to as the Teagasc MACC. It suggests a mix of different farming practices combined with a reduction in the beef producing cattle herd alongside a small increase in the dairy herd. An increase in organic farming is identified as a contributor to achieving reduced emissions, but there is an alternative that is less palatable for many and less in keeping with Ireland’s ‘green’ image and maximum use of grazed grass.

If Ireland was to convert to industrial farming for beef and dairy production, a significant increase in output could be achieved with less units of livestock and therefore less emissions.

Genetics exist to produce very high output dairy cows with massive milk yields. These are kept inside to conserve energy with an ad lib feed diet to maximise output during a short life cycle.

Similarly with beef. While many cattle are finished in sheds in the final few weeks before going to the factory, it would be more efficient if they were kept indoors all the time with intensive feeding. This would deliver slaughter weights at a much younger age with correspondingly less emissions. Ireland and the EU could go further and embrace the North American model of using growth-promoting hormones to further reduce the number of cattle required to produce the same volume of beef.

Another option, and one particularly favoured by advocates of a vegetarian or even vegan diet, is that society should eliminate or seriously reduce meat and dairy consumption.

Aside from the generally accepted positive contribution meat and dairy make to the human diet, the reality is that this is a bit like asking consumers to switch from using their car and use public transport or even turn down the heating and put on more clothes.

That said, society in the developed world has reached peak meat and dairy consumption; future growth and demand will come from the developing world, Asia in the short-term and Africa in the longer term.

Where do Irish farmers stand?

Despite the debate we can have about why Irish agriculture should be exempt from the most stringent emissions targets, the reality is that they are now law and farmers are instinctively law-abiding people. The wins from farming techniques identified in the Teagasc MACC need to be embraced.

Similarly, switching to organic farming is a real option for many already quasi organic farmers that keep a relatively small number of cattle on more marginal land.

An ageing farmer population and miniscule margins from beef and sheep production over a long period have already seen a reduction in the suckler herd and this is likely to continue.

Maximising supports

Dairy farming is forecast to expand further, and it is striking that the need to have more acres to comply with nitrates requirement is squeezing tillage farmers out in many cases.

It is difficult to see how farmers can turn Government policy back from its present direction. If that cannot be achieved, then reality has to be faced and farmers should maximise their share of supports the Government have put in place to support current policy.

This may not be what production-orientated farmers would want, but if it is the reality then there will be no choice. Perhaps in time the policy will change. In the last century it was policy to run down the railway network – now Government is exploring the feasibility of re-opening some long-closed routes.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: