Two weeks ago, we demonstrated how a 40ha, 45-cow suckler farm could achieve an additional €186 net profit per cow annually by utilising an extra two tonnes of grass per hectare – a modest target given current grassland performance on beef farms.

Then, in last week’s issue, we found an extra €84 per cow where a 40ha, 53-cow farm switched from 36- to 24-month heifer calving. While these figures apply to farms that push hard for output, they demonstrate the vast potential that currently exists for improvement on suckler farms across the country.

Where we’re at

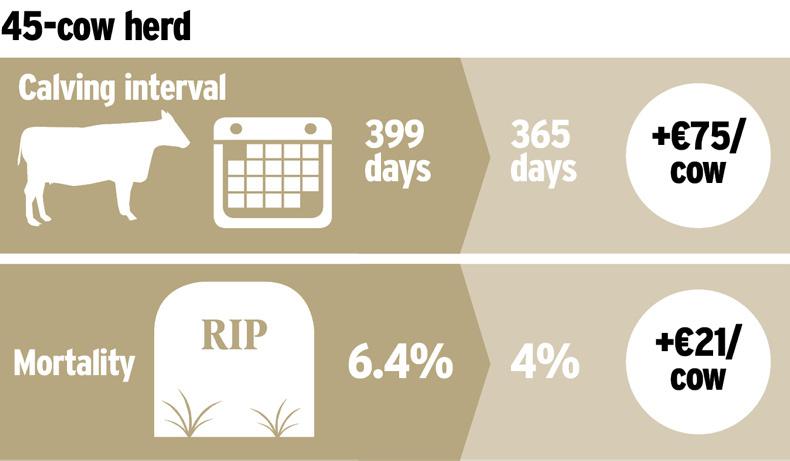

The average Irish cow herd has a calving interval of 399 days, a 28-day mortality rate of 6.4%, a calves/cow figure of 0.83, and a “females not calved” figure of 9%. It’s important to understand these figures – they are some of the key performance indicators of suckler farm performance.

For me, the calves/cow figure tells you all you need to know: it takes into account calving interval, uncalved females and mortality – three precise areas from which the Irish suckler herd is haemorrhaging money.

Calves/cow: (365/your calving interval figure) x (number of calves alive at 28 days/number of eligible females).

The countrywide average is 0.83, while top farms are doing in excess of 0.95. What does this mean? In a given 365-day period, a top-performing 50-cow herd has an extra trailer-load of calves to sell.

While every individual farm hectare should be treated as an asset and pushed as hard as soil type, labour and finance allows, so too should every cow. As a cohort – myself included sometimes – we are too fond of our suckler cows and not fond enough of money in the pocket. We need to learn to let go. A sports manager or business person doesn’t tolerate under-performers on their teams – this is the first mindset change that’s needed.

we are too fond of our suckler cows and not fond enough of money in the pocket

Two sides to calving interval

In truth, I have yet to come across a suckler herd full of poor cows. The norm is a small number of top-class animals, a lot of good cows and a further small number of terrible animals – these “terribles” drive averages the wrong way.

If 18 cows in a 20-cow herd have a 365-day interval and the other two are allowed to take a year-long career break, the herd’s average will be 401 days. While this mightn’t affect calving date the way a herd-wide 401-day interval would, it still represents around €1,550 per year less in the farmer’s pocket versus a herd average of 365 days.

So, when looking at calving interval, we really need to look at the “females not calved figure” too. If this is low (zero is the target), but the interval is high, then the herd as a whole is slipping – which is quite rare. If this “not calved” figure is high then it’s probably a small number of ladies doing all of the interval damage – much more common. Aside from a freak disease outbreak, both scenarios are management-driven and avoidable.

Preventing mortality begins well before calving. Firstly, is she a known hard-calver? If so, why is she still in the herd? What about the sire? An export-standard calf doesn’t necessarily need to come into the world in a barrage of bawling, sweating or pulling, or worse. There are plenty of proven sires out there whose progeny arrive small and swell quickly.

Could AI be considered as a means to increase reliability around difficulty? Are your cows getting enough pre-calver mineral? They should be consuming 100g per day, 30g of which being magnesium. Be liberal. This will help prevent calving difficulty.

Are your cows on track condition-wise? (See this week’s Focus supplement.) Fat cows might be too lazy to calve and overly thin cows might lack the capacity to do it themselves. Are your calves getting enough colostrum in on day one? If you’re not sure, don’t assume.

Scour is a common cause of mortality in the calf’s initial weeks. Are your cows vaccinated? If animals can’t get outside soon after calving, do you need to think about putting in a creep facility? Is your calf lie-back clean enough and bedded daily? Do you need to rethink your calving date completely? Perhaps it’s too early in the year.

Money talk

Be it a whole-herd slip or a couple of cows spoiling the party for everyone, add €2.20 daily per cow for every day that the average herd calving interval creeps beyond 365 days. Pulling a herd average from 399 to 365 days represents an additional €75/cow.

Looking simply at herd mortality, bringing 28-day mortality from the national average of 6.4% to 4% (the target being sub-five), represents a gain of around €21 per cow. This figure takes into account a modest lost profit of €150 as well as one less slaughter animal to spread fixed costs over and cow maintenance costs. Choosing to replace this animal straightaway may push it further, depending on cull cow price and what will fill the void. As will the purchase of a foster-calf, depending on its quality.

Combined, these measures increase net profit by €96 per cow in a 45-cow herd – over €4,300.

Print your ICBF Herdplus calving report. What’s your calving interval? If it’s greater than 375 days, flick to the back pages and look at the cow list, which should be sorted in order of decreasing calving interval. Are there cows that took a year out and weren’t culled, ie “females not calved in period”? If so, why? The above question is a rhetorical one – there is absolutely no excuse for a commercial cow to be granted such a chance. Consider a pre-breeding scan, or at least a scan mid-breeding season on any cows that haven’t shown heat 50-55 days post-calving.If your mortality was high in 2016, up your pre-calver mineral dosage and evaluate whether all cows are getting enough in restricted feeding situations.Ensure every calf receives colostrum in the hours post-calving.Where calves can’t get out, be liberal with straw.

Two weeks ago, we demonstrated how a 40ha, 45-cow suckler farm could achieve an additional €186 net profit per cow annually by utilising an extra two tonnes of grass per hectare – a modest target given current grassland performance on beef farms.

Then, in last week’s issue, we found an extra €84 per cow where a 40ha, 53-cow farm switched from 36- to 24-month heifer calving. While these figures apply to farms that push hard for output, they demonstrate the vast potential that currently exists for improvement on suckler farms across the country.

Where we’re at

The average Irish cow herd has a calving interval of 399 days, a 28-day mortality rate of 6.4%, a calves/cow figure of 0.83, and a “females not calved” figure of 9%. It’s important to understand these figures – they are some of the key performance indicators of suckler farm performance.

For me, the calves/cow figure tells you all you need to know: it takes into account calving interval, uncalved females and mortality – three precise areas from which the Irish suckler herd is haemorrhaging money.

Calves/cow: (365/your calving interval figure) x (number of calves alive at 28 days/number of eligible females).

The countrywide average is 0.83, while top farms are doing in excess of 0.95. What does this mean? In a given 365-day period, a top-performing 50-cow herd has an extra trailer-load of calves to sell.

While every individual farm hectare should be treated as an asset and pushed as hard as soil type, labour and finance allows, so too should every cow. As a cohort – myself included sometimes – we are too fond of our suckler cows and not fond enough of money in the pocket. We need to learn to let go. A sports manager or business person doesn’t tolerate under-performers on their teams – this is the first mindset change that’s needed.

we are too fond of our suckler cows and not fond enough of money in the pocket

Two sides to calving interval

In truth, I have yet to come across a suckler herd full of poor cows. The norm is a small number of top-class animals, a lot of good cows and a further small number of terrible animals – these “terribles” drive averages the wrong way.

If 18 cows in a 20-cow herd have a 365-day interval and the other two are allowed to take a year-long career break, the herd’s average will be 401 days. While this mightn’t affect calving date the way a herd-wide 401-day interval would, it still represents around €1,550 per year less in the farmer’s pocket versus a herd average of 365 days.

So, when looking at calving interval, we really need to look at the “females not calved figure” too. If this is low (zero is the target), but the interval is high, then the herd as a whole is slipping – which is quite rare. If this “not calved” figure is high then it’s probably a small number of ladies doing all of the interval damage – much more common. Aside from a freak disease outbreak, both scenarios are management-driven and avoidable.

Preventing mortality begins well before calving. Firstly, is she a known hard-calver? If so, why is she still in the herd? What about the sire? An export-standard calf doesn’t necessarily need to come into the world in a barrage of bawling, sweating or pulling, or worse. There are plenty of proven sires out there whose progeny arrive small and swell quickly.

Could AI be considered as a means to increase reliability around difficulty? Are your cows getting enough pre-calver mineral? They should be consuming 100g per day, 30g of which being magnesium. Be liberal. This will help prevent calving difficulty.

Are your cows on track condition-wise? (See this week’s Focus supplement.) Fat cows might be too lazy to calve and overly thin cows might lack the capacity to do it themselves. Are your calves getting enough colostrum in on day one? If you’re not sure, don’t assume.

Scour is a common cause of mortality in the calf’s initial weeks. Are your cows vaccinated? If animals can’t get outside soon after calving, do you need to think about putting in a creep facility? Is your calf lie-back clean enough and bedded daily? Do you need to rethink your calving date completely? Perhaps it’s too early in the year.

Money talk

Be it a whole-herd slip or a couple of cows spoiling the party for everyone, add €2.20 daily per cow for every day that the average herd calving interval creeps beyond 365 days. Pulling a herd average from 399 to 365 days represents an additional €75/cow.

Looking simply at herd mortality, bringing 28-day mortality from the national average of 6.4% to 4% (the target being sub-five), represents a gain of around €21 per cow. This figure takes into account a modest lost profit of €150 as well as one less slaughter animal to spread fixed costs over and cow maintenance costs. Choosing to replace this animal straightaway may push it further, depending on cull cow price and what will fill the void. As will the purchase of a foster-calf, depending on its quality.

Combined, these measures increase net profit by €96 per cow in a 45-cow herd – over €4,300.

Print your ICBF Herdplus calving report. What’s your calving interval? If it’s greater than 375 days, flick to the back pages and look at the cow list, which should be sorted in order of decreasing calving interval. Are there cows that took a year out and weren’t culled, ie “females not calved in period”? If so, why? The above question is a rhetorical one – there is absolutely no excuse for a commercial cow to be granted such a chance. Consider a pre-breeding scan, or at least a scan mid-breeding season on any cows that haven’t shown heat 50-55 days post-calving.If your mortality was high in 2016, up your pre-calver mineral dosage and evaluate whether all cows are getting enough in restricted feeding situations.Ensure every calf receives colostrum in the hours post-calving.Where calves can’t get out, be liberal with straw.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: