Forecasts and reality can diverge dramatically but trends are much more stable. Forecasts for product prices and output can be spectacularly inaccurate if weather patterns change in a given year in an important crop producing region. They can also change if an important input such as oil or fertiliser spikes in price and significantly affects the price of inputs and the cost of production.

Producers in individual countries can also be dramatically affected by political decisions. Ethiopian farmers receive more for their grain than do their European counterparts and, over the last seven to eight years, we have seen an extraordinary convergence in dairy prices between New Zealand and Europe. Up to 2010, New Zealand dairy farmers had received about half the European price for milk – now they are, if not slightly above, Irish prices.

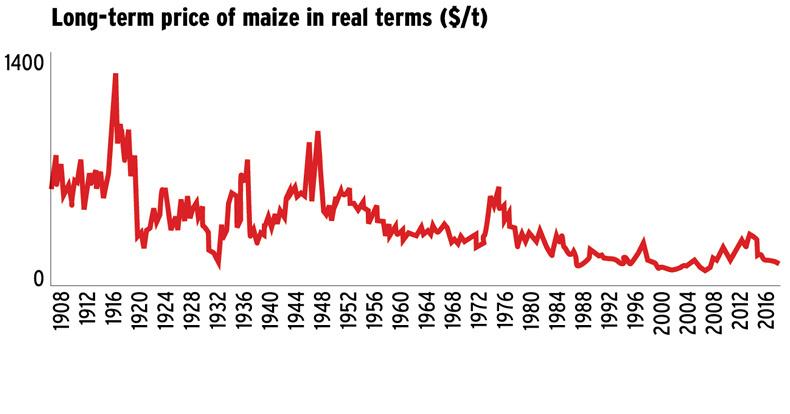

But over the long-term, the trend in agricultural prices is unmistakable. The latest Agricultural Outlook produced by the OECD, the rich world economies and the FAO, the Food & Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations, has a spectacular graph showing the long-term trends in the price of maize for more than the last 100 years. As can be seen from the graph, the real price has fluctuated wildly with war time booms and peace time slumps. We have now essentially reached a stage in world food production where scarcity for those in normal, peaceful democracies is a remote possibility and if there is a regional, climatic problem as in east Africa at the moment, there are more than enough stocks available to deliver aid without worldwide price shocks.

So, what can be expected for the next 10 years? The prognosis is more of the same – in other words a rough continuation of the present trends with some small increases in cereals and some dairy products and a decline in meat, especially beef prices, as demand growth slows and production continues to steadily increase.

The OECD/FAO forecast should reinforce the case for at least a stability in EU funding for the CAP as the next review begins. For individual farmers, the relentless drive to reduce costs or to differentiate their product from the bulk commodities of overseas, large-scale producers will continue. But one clear message is that those who expect biofuels to be the saviour of the tillage sector will be disappointed. On the other hand, those who calmly assess where their comparative advantage lies and develop accordingly, should be able to ride out most storms in bad times and do well on average. For Irish producers, that seems to imply dairying as the key enterprise.

SHARING OPTIONS