Farmers have been in the starting blocks to produce energy crops and biogas to replace fossil fuels, trying to figure out if they can make an income from this new business. But another question has received less attention: will those fuels meet compulsory EU environmental criteria?

The Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) has commissioned an independent study to answer this question and the answer is, broadly, yes – but it won’t always be easy.

The second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) applicable from 2021 to 2030 will require bioenergy to save 70% greenhouse gas emissions compared to the fossil fuels it replaces – 80% from 2026.

If green fuels are to count towards Ireland’s renewable targets, the growers, processors and distributors of biomass will have to measure emissions from cultivation, transformation and transport.

They will also need to ensure that their products did not cause deforestation or the destruction of protected wildlife habitats, peatlands and wetlands. Imports will have to come from countries that have ratified the Paris climate agreement.

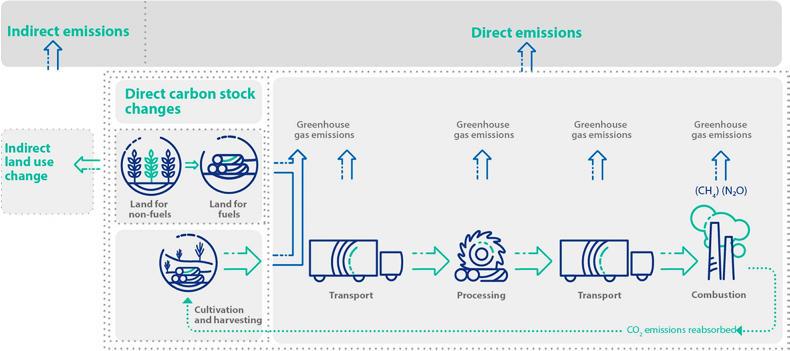

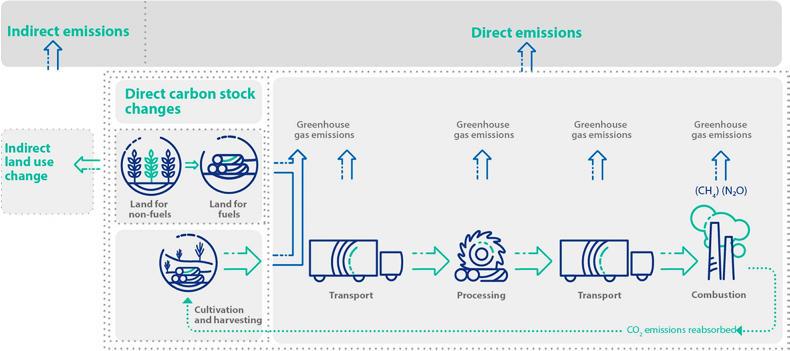

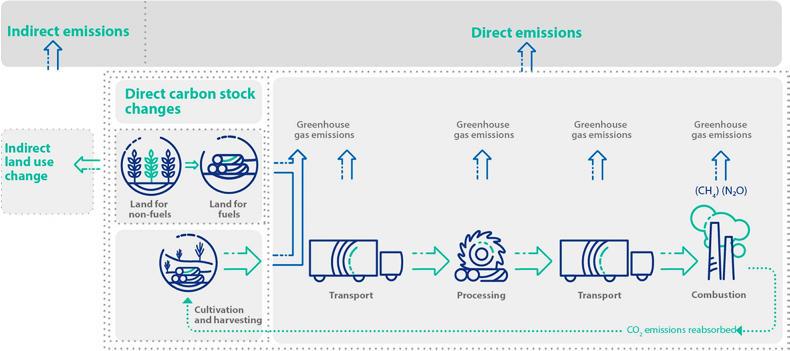

The GHG emissions generated from biomass used for energy generation can arise at four stages in their life cycle. \ SEAI

The study found that all biomass harvested in Ireland complies with the conservation requirements.

This leaves greenhouse gas emissions, which can be reported using EU sample values or real-life measurements by the industry.

The SEAI supplied calculations for miscanthus, willow and grass silage, which are important in Ireland but weren’t on the EU’s sample list.

“Miscanthus comes out well,” SEAI bioenergy manager Matthew Clancy told the Irish Farmers Journal, adding that willow also scored high across sustainability indicators. While these crops generate low emissions if used as chips, energy use will be a challenge if they’re pelleted.

"Cultivation is the other big source of emissions,” Clancy said, and Teagasc has been exploring safe ways of using sewage sludge on willow instead of synthetic fertiliser.

Grass silage, too, risks going over the limit if used on its own to make biogas.

However, slurry is the most carbon-efficient source of bioenergy on the EU list, and combining up to 40% of grass silage with slurry can meet sustainability criteria if the right technologies are used.

Farmers currently don’t grow grass for energy, they grow it for animals

“The good news is the huge potential,” Clancy said, with anaerobic digestion of grass and slurry capable of covering “a large part of Ireland’s energy needs”.

“The bad news is that there’s a nitrogen fertiliser used to grow grass and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as its cost.” Digestate left over from the process would also need to be stored in enclosed tanks and used as fertiliser.

Yet Clancy stressed that the study was based on existing farming practices.

“Farmers currently don’t grow grass for energy, they grow it for animals,” he said. Incorporating red clover in swards could improve carbon efficiency.

Regarding costs, Clancy said existing technologies require at least 5,000t of slurry per year to be profitable, ruling them out for farm-sized projects in Ireland.

“We’re pushing hard for new technologies that you could put in a slurry tank on your farm,” he said.

Pilot projects will demonstrate farm-based gas production soon and farmers should “wait and see,” he added.

In the meantime, the most sustainable source of bioenergy will remain forest residues and thinnings, with Irish-grown wood better placed than imports from countries like the US, where Bord na Mona briefly considered building a wood pellet plant one year ago.

“The people who planted forestry 20 years ago will have crops ready for thinning under the Sustainable Scheme for Renewable Heat (SSRH) and this is the most robust supply chain from a sustainability point of view,” said Clancy.

Read more

Use AD to produce gas, reduce emissions and grow more grass – SEAI

Should we ditch CAN fertiliser?

Climate policy must ‘work with farmers' – Naughton

Farmers have been in the starting blocks to produce energy crops and biogas to replace fossil fuels, trying to figure out if they can make an income from this new business. But another question has received less attention: will those fuels meet compulsory EU environmental criteria?

The Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI) has commissioned an independent study to answer this question and the answer is, broadly, yes – but it won’t always be easy.

The second Renewable Energy Directive (RED II) applicable from 2021 to 2030 will require bioenergy to save 70% greenhouse gas emissions compared to the fossil fuels it replaces – 80% from 2026.

If green fuels are to count towards Ireland’s renewable targets, the growers, processors and distributors of biomass will have to measure emissions from cultivation, transformation and transport.

They will also need to ensure that their products did not cause deforestation or the destruction of protected wildlife habitats, peatlands and wetlands. Imports will have to come from countries that have ratified the Paris climate agreement.

The GHG emissions generated from biomass used for energy generation can arise at four stages in their life cycle. \ SEAI

The study found that all biomass harvested in Ireland complies with the conservation requirements.

This leaves greenhouse gas emissions, which can be reported using EU sample values or real-life measurements by the industry.

The SEAI supplied calculations for miscanthus, willow and grass silage, which are important in Ireland but weren’t on the EU’s sample list.

“Miscanthus comes out well,” SEAI bioenergy manager Matthew Clancy told the Irish Farmers Journal, adding that willow also scored high across sustainability indicators. While these crops generate low emissions if used as chips, energy use will be a challenge if they’re pelleted.

"Cultivation is the other big source of emissions,” Clancy said, and Teagasc has been exploring safe ways of using sewage sludge on willow instead of synthetic fertiliser.

Grass silage, too, risks going over the limit if used on its own to make biogas.

However, slurry is the most carbon-efficient source of bioenergy on the EU list, and combining up to 40% of grass silage with slurry can meet sustainability criteria if the right technologies are used.

Farmers currently don’t grow grass for energy, they grow it for animals

“The good news is the huge potential,” Clancy said, with anaerobic digestion of grass and slurry capable of covering “a large part of Ireland’s energy needs”.

“The bad news is that there’s a nitrogen fertiliser used to grow grass and greenhouse gas emissions, as well as its cost.” Digestate left over from the process would also need to be stored in enclosed tanks and used as fertiliser.

Yet Clancy stressed that the study was based on existing farming practices.

“Farmers currently don’t grow grass for energy, they grow it for animals,” he said. Incorporating red clover in swards could improve carbon efficiency.

Regarding costs, Clancy said existing technologies require at least 5,000t of slurry per year to be profitable, ruling them out for farm-sized projects in Ireland.

“We’re pushing hard for new technologies that you could put in a slurry tank on your farm,” he said.

Pilot projects will demonstrate farm-based gas production soon and farmers should “wait and see,” he added.

In the meantime, the most sustainable source of bioenergy will remain forest residues and thinnings, with Irish-grown wood better placed than imports from countries like the US, where Bord na Mona briefly considered building a wood pellet plant one year ago.

“The people who planted forestry 20 years ago will have crops ready for thinning under the Sustainable Scheme for Renewable Heat (SSRH) and this is the most robust supply chain from a sustainability point of view,” said Clancy.

Read more

Use AD to produce gas, reduce emissions and grow more grass – SEAI

Should we ditch CAN fertiliser?

Climate policy must ‘work with farmers' – Naughton

SHARING OPTIONS