Dairy farmers who have fixed a substantial proportion of their milk are in terrible difficulty.

We have featured their plight prominently in the paper in recent weeks, and rightly so. The reality is that we’ll be returning to that story repeatedly in the coming months, as no easy solutions present themselves.

The awful thing is it’s in many cases the most prudent of farmers who are at the receiving end of the sudden transformation of both the cost base of milk production and the farmgate price.

The logic of a decision that seemed sensible, to fix a proportion of milk to guard against price volatility, was upended by the senselessness of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

It is also true that some farmers who have fixed a lot of their milk forward are the most financially exposed and vulnerable. People who had invested in land, either bought or long-term leased, and infrastructure to turn that land into a milking platform may have fixed to ensure a steady repayment capacity.

It seems blindingly obvious now, but such schemes would have benefited from a related feed-fertiliser forward purchase mechanism, to control major production costs. To Glanbia’s credit, I understand it introduced such a facility to the early schemes, but farmers didn’t like it.

It is not just milk that is forward sold. Some grain farmers have been selling forward for over a decade now. And they have been similarly caught out.

I’m one of those farmers who has sold barley forward, as it happens. In November, I forward sold 20% of the malting barley I agreed to grow this year for Boortmalt. The €250/t on offer was essentially a record price. My thinking at the time was that if that was the worst price I got for barley, I could hardly lose money. In February, the price had gone up to €270, and I took another 20%.

And then Putin invaded Ukraine, and everything changed.

I’ve been burnt before, back in one of the first years where selling forward was allowed, 2012 I think. The price leaped by about €40/t, and I was out of pocket.

I made it back the next year by selling forward again, with the early price much better than the harvest price.

Like many things in life, forward selling really only works if you stick with it.

The reality of selling forward is that you don’t do it to make money, it’s not speculating as such. You do it to provide some certainty into your business, and to reduce your exposure to the risk of volatility.

This year is on an entirely different level, however. The harvest price last year saw feed barley make about €210, it is currently north of €330. Malt barley is currently running at well over €400.

The €150/t gap between the barley price I have agreed and the current price is a yawning chasm.

What happened in 2012 put many people off forward selling forever. I looked on it as within the vagaries of price variation - a 25% jump.

I’m hurting now. The price has doubled in only a few months. My forward price, averaging €260/t for 40% of my contracted acreage, could be €170/t off the final price.

If that happens, for every 10t of grain I deliver, I will be “losing” €680 of price potential. That’s a grand for every typical grain trailer load.

It might be small beer compared to the plight of dairy farmers with 80% of their milk on fixed price schemes, but it will still hurt a lot.

I fully intend to fulfil my contract, but I will be watching with interest to see if Boortmalt mirrors the dairy co-ops in recognising the unique dynamic at play. Will there be any effort made, any gesture from the maltster and its customers?

With forward sales, a “back-to-back” deal is usually completed. The company buying from the farmer goes to the market, sees what price it can get, and offers a related price back to the farmer. Both deals are interdependent, which makes it difficult to easily renegotiate the deal, no matter how changed the circumstances.

One notable distinction between the likes of Glanbia’s milk and Boortmalt’s grain is the relative simplicity of the grain supply chain.

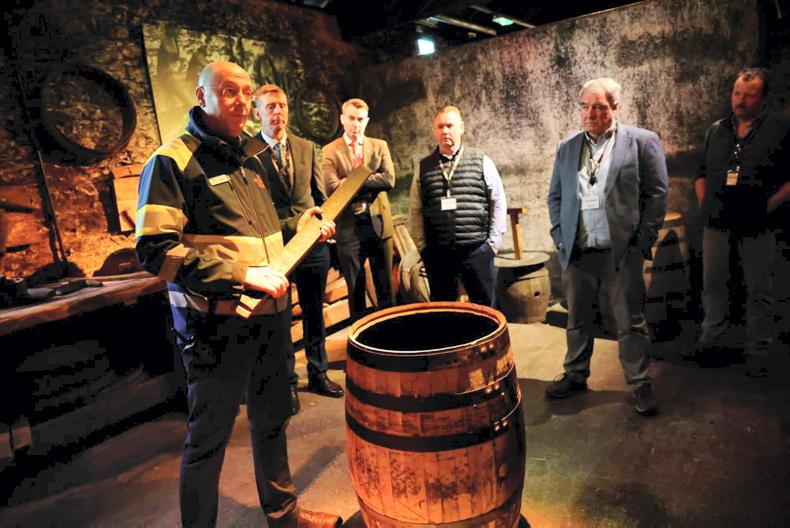

Essentially, Boortmalt turn barley into malt for distillers and brewers. There are only a handful of customers. Some of them make great play of how close they are to the farmer, with glossy TV ads of golden barley cascading into a trailer on a sunlit afternoon switching to a pint of lager or stout.

Will that short supply chain offer an opportunity for the gap between the early forward price and the current market to be bridged to some degree?

There is another factor that Boortmalt might need to consider. The contract, once with Guinness, then with Minch Norton, which evolved into Greencore grain before being sold to Boortmalt, has itself evolved.

Once a sacrosanct document, with an exact tonnage passed on from father to son or daughter, it’s now more ad-hoc. Farmers agree an acreage with Boortmalt, and buy enough seed to plant that acreage.

There hasn’t been a contract to sign for a couple of years now.

Over the last couple of growing seasons there has been a lot of uncertainty around contracts. Boortmalt had difficulties caused by the fire at their Maltings in Athy.

As a grower I heard stories where the tonnage or the proportion of brewing to malting contract would be adjusted. As a journalist I recounted what was being openly discussed at farmers’ meetings.

In the event, there were no such cuts. Demand for malt quality barley held up last year, and it was all taken.

In 2020, quality was variable, so Boortmalt took any crop that passed muster. In 2018, yields were horribly affected by the drought, particularly in the south Kildare-Carlow area where so much malt barley is grown, and in south Wexford.

But it seemed Boortmalt reserved the right to move the goalposts if the game wasn’t going its way.

In addition, Boortmalt has effectively franchised out some of the assembly of malting barley to independent merchants.

With all that in mind, it’s fair to say the strength of the links between growers and Boortmalt, loosened by the changed nature of contractual arrangements, and by Boortmalt’s gradual withdrawal from the sale of inputs like pesticides and fertiliser, could do with the boost a gesture of solidarity would provide.

SHARING OPTIONS