While 2018 was a tough year for many Irish farmers coping with a range of weather extremes, particularly in the south and east, meat output increased across all the species.

Bord Bia reported on all to a packed room at its meat marketing seminar, the third industry event of the week following the performance and prospects launch and livestock exports seminar earlier in the week.

Delegates also heard a 10-year view on the prospects for the global meat industry from Richard Brown (Gira Consulting) and the potential of southeast Asia, apart from China, from Ciaran Gallagher who is based in Bord Bia’s Singapore office.

Latest consumer trends, including veganism, were presented and it is impossible to have a food industry event without the issue of Brexit being highlighted.

Carole Lynch from BDO gave an outline of the WTO tariffs that become applicable if there is a no-deal Brexit and of particular interest to the meat traders at the event, the paperwork that is required for trade with the UK as a third country and its cost. The seminar concluded with an explanation of Bord Bia’s meat marketing strategy and its people development programmes.

Beef and live cattle exportsThe Irish beef industry is the largest meat-producing category and Bord Bia’s Mark Zeig reported that with almost 1.8m cattle going through the factories in 2018, it was a 20-year high.

Live exports were also up in numbers but there was a big switch from older cattle to calves, meaning that the value dropped dramatically.

Beef export volumes increased 3% in 2018 to 573,000t carcase weight equivalent (CWE) though value increased just 1% to €2.5bn.

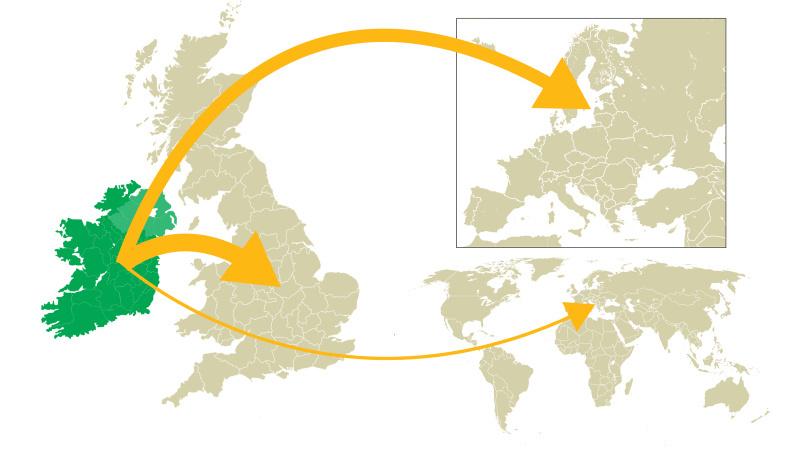

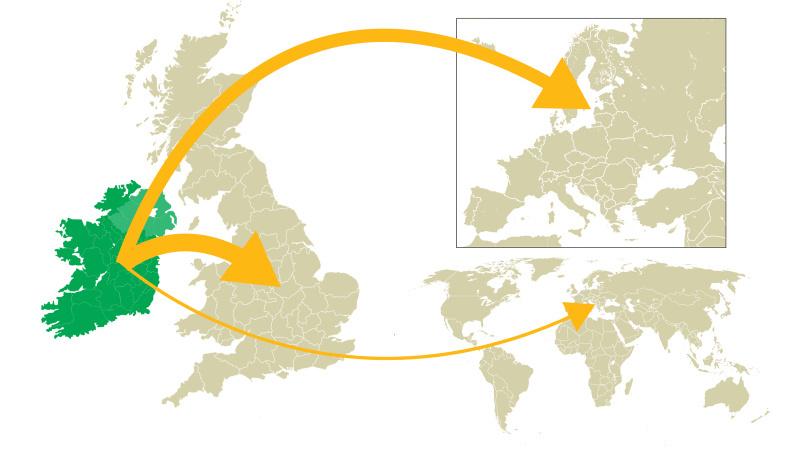

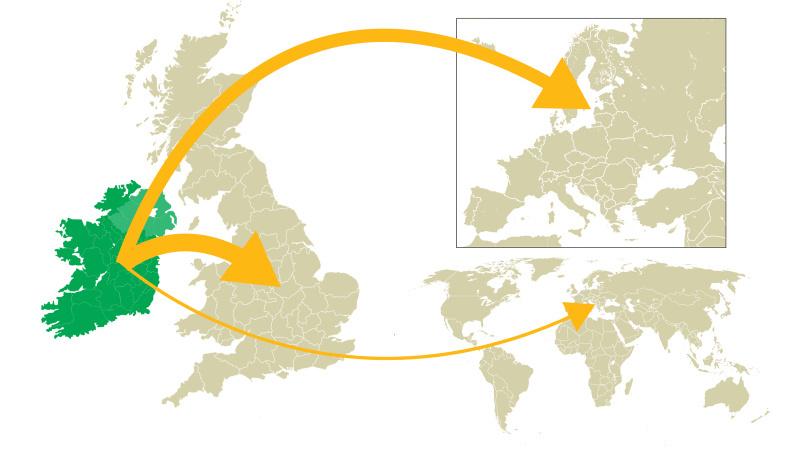

Ireland’s dependence on the UK market is reflected in the 298,000t that it imported from Ireland, which is 52% of all beef exports. The rest of the EU took 250,000t or 44% of total exports meaning that just 4% of Irish beef was sold outside the EU last year including 1,000t to China which opened as a market for the first time.

Trade flows

On prices, it was a mixed year for farmers, with prices climbing from the start of the year and then falling back for the remainder, with the old trend of prices beginning to increase again from November failing to happen in 2018.

Part of the difficulty was EU imports increasing by 11.3% over the course of the year to 288,587t between January and October, while EU exports declined by 6%.

Three-quarters of EU beef imports come from Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay, after a collapse in the Brazilian and Argentinian currencies made their beef particularly competitive in 2018.

Live exports

Following from the live exports seminar the previous day, Joe Burke presented a summary of the main changes in 2018. The profile of live cattle exports from Ireland changed significantly in 2018 compared with the previous year. The Turkish market for adult cattle collapsed from 30,600 in 2017 to 12,900 last year, while calf exports surged by 55% to 158,000 head. Sales to the north were down again to just over 24,645 and just 5,488 cattle were exported to Britain.

Numbers on the ground

The end of 2018 had factory kills over 40,000 in most weeks and looking at the AIMS data up to November, there were 11,000 more male cattle between 24 and 36 months still in the system, though there were 5,000 fewer heifers than the previous year. In the 12 to 24 month category, there were 15,000 less male cattle up to November but 22,000 more heifers.

When it comes to young cattle less than a year old, numbers of males were down 55,000 and females were down 30,000 last year compared with 2017 which suggests the Irish factry kill which has been on an upward trend will level off in 2019.

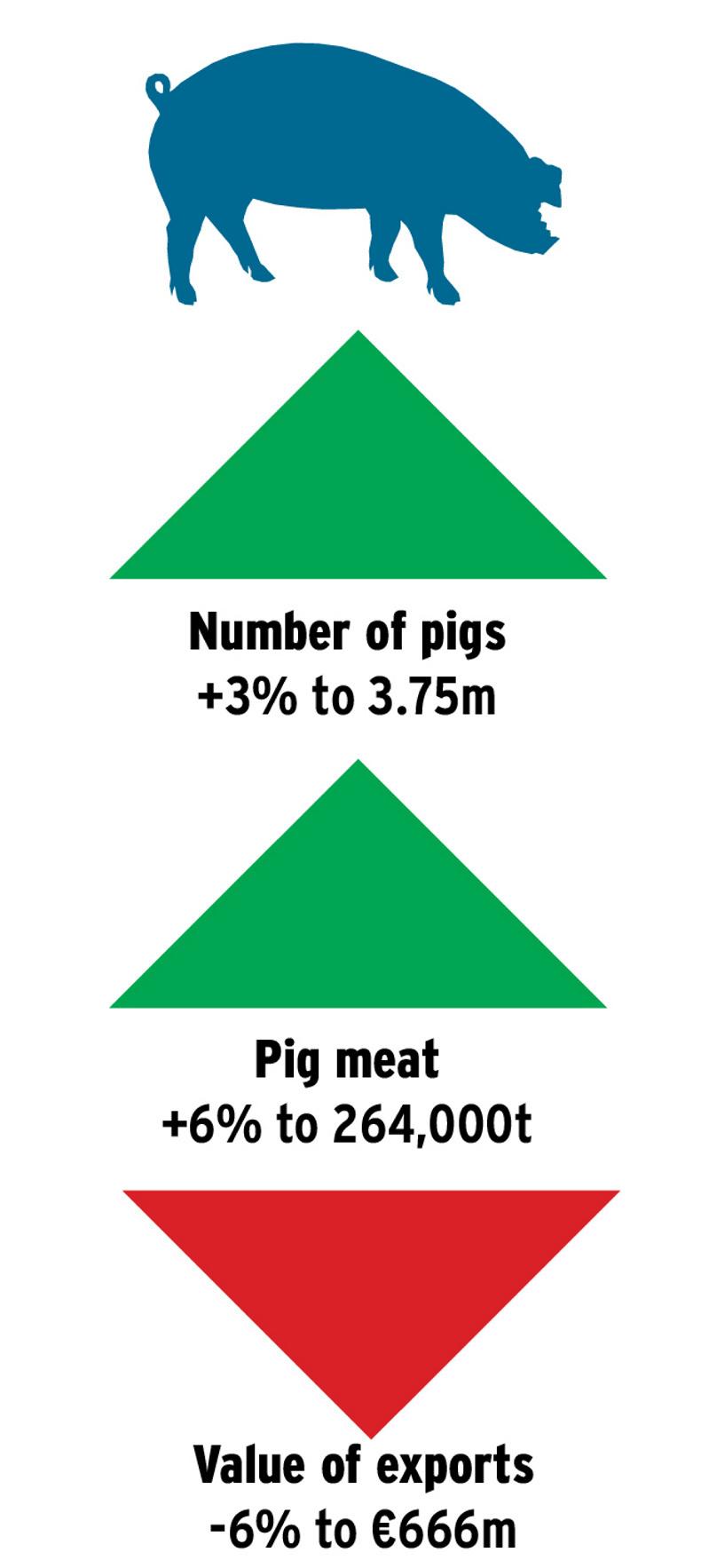

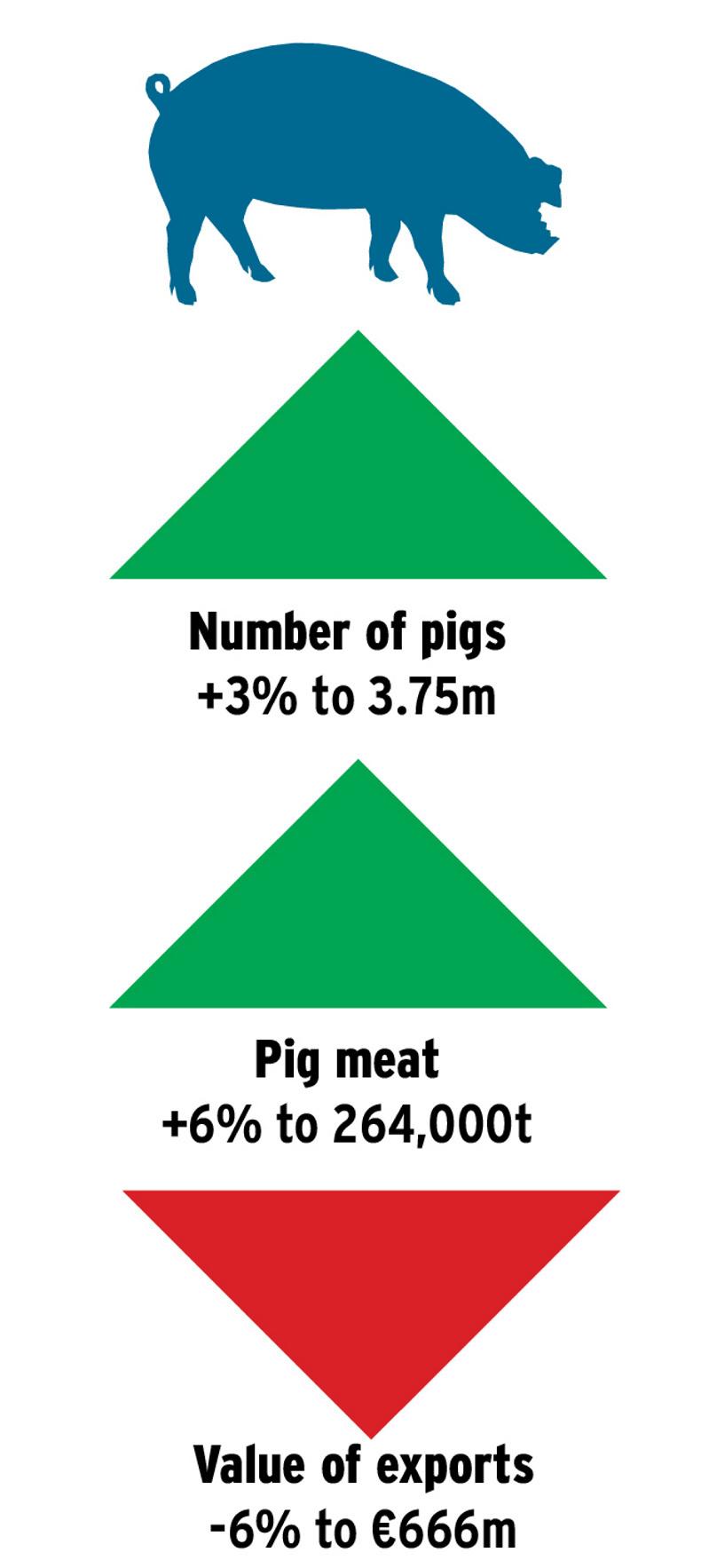

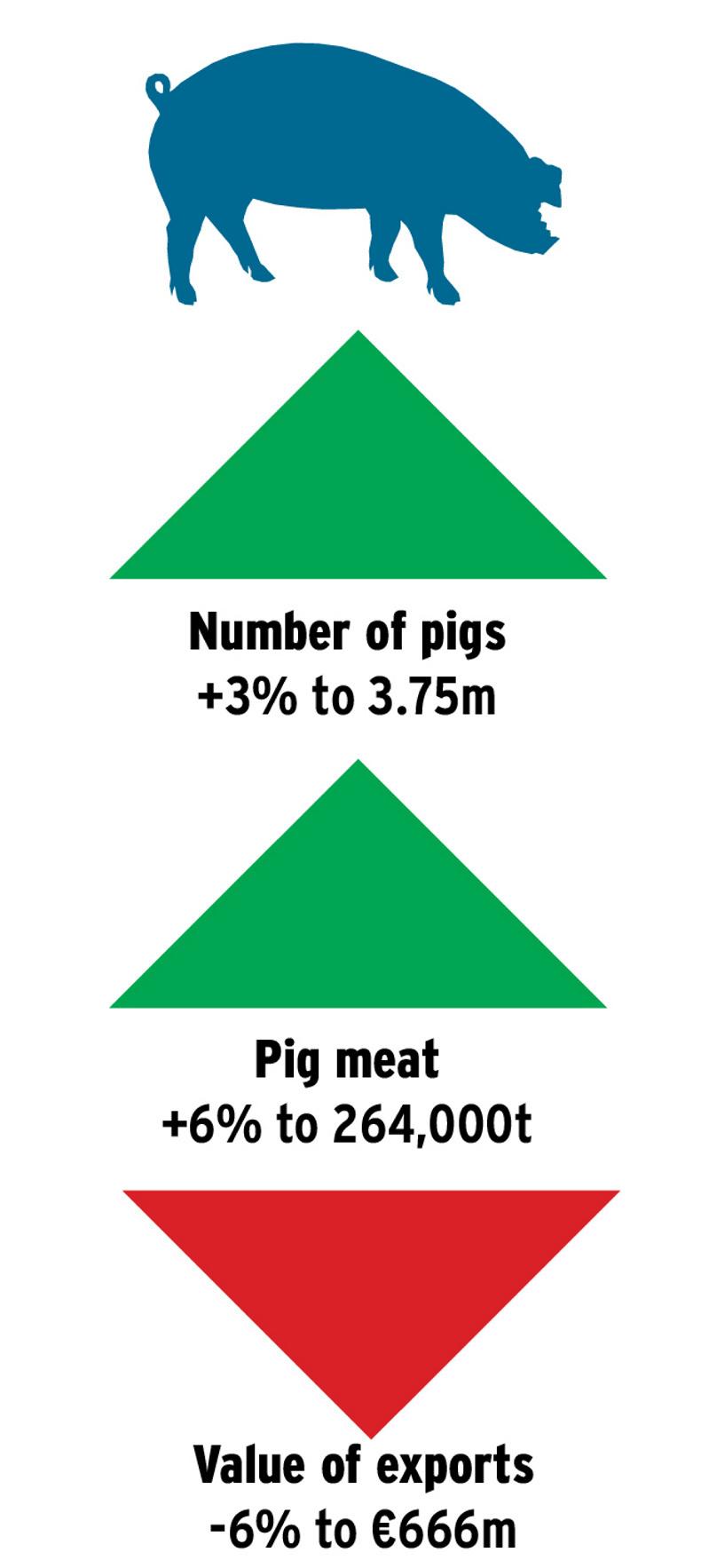

Bord Bia’s Peter Duggan explained that 2018 was a forgettable year for pig farmers as pig prices fell from September 2017 and have been hovering at around €1.40/kg or below for much of the year, a loss-making position.

Weak prices meant that although the volume of pig meat exports was up 6% on 2017 at 264,000t, the value was down 6% at €666m. Pig numbers were up 3% to 3.75m, of which 466,000 were exported live, predominantly to Northern Ireland.

An already difficult market in 2018 was made worse by the outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) and a major cull of the pig herd in China which led to a drop in import demand on an already well-supplied global market. A further complication in 2018 was the launch of a trade war with China by US President Donald Trump which has the potential to cause further disruption this year when US production is forecast to reach a record 12m tonnes.

It is thought that the fallout of the major pig cull in China last year will be a scarcity of supply in 2019 and Ireland and the EU would expect to benefit from any deficit and increase export volumes to China, with hopefully a corresponding lift in farmgate prices.

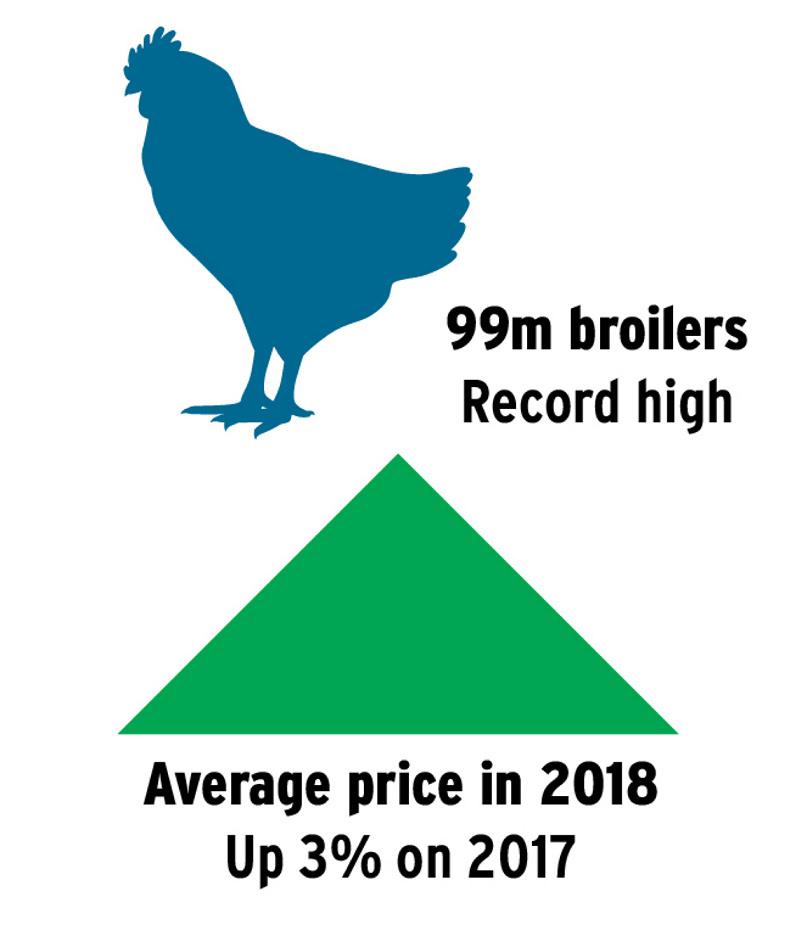

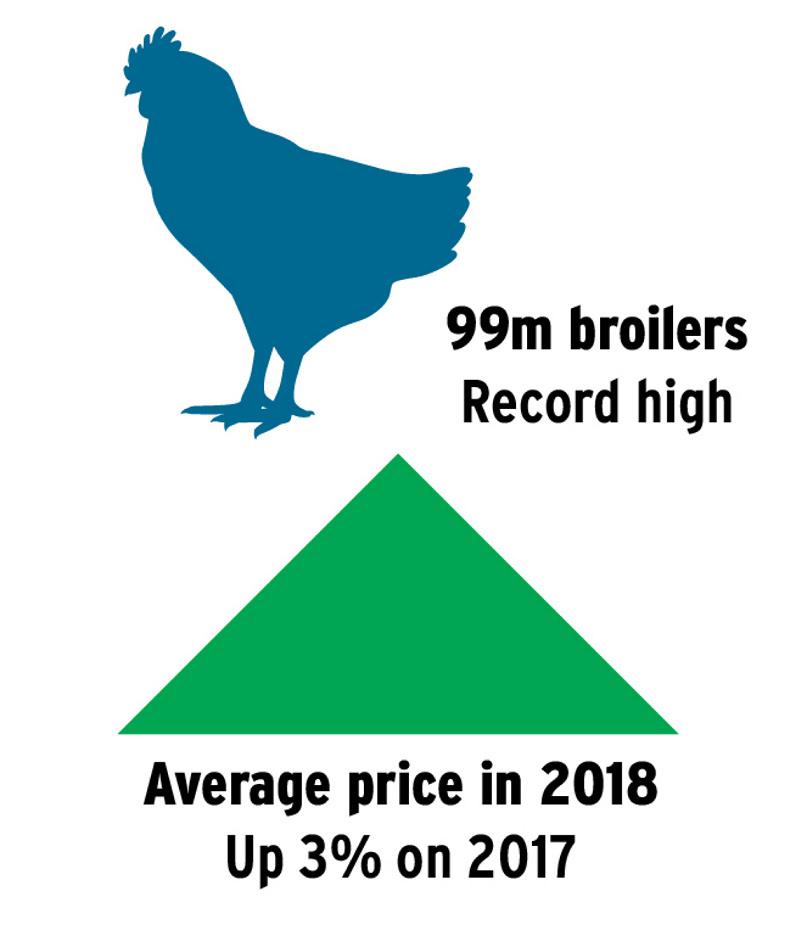

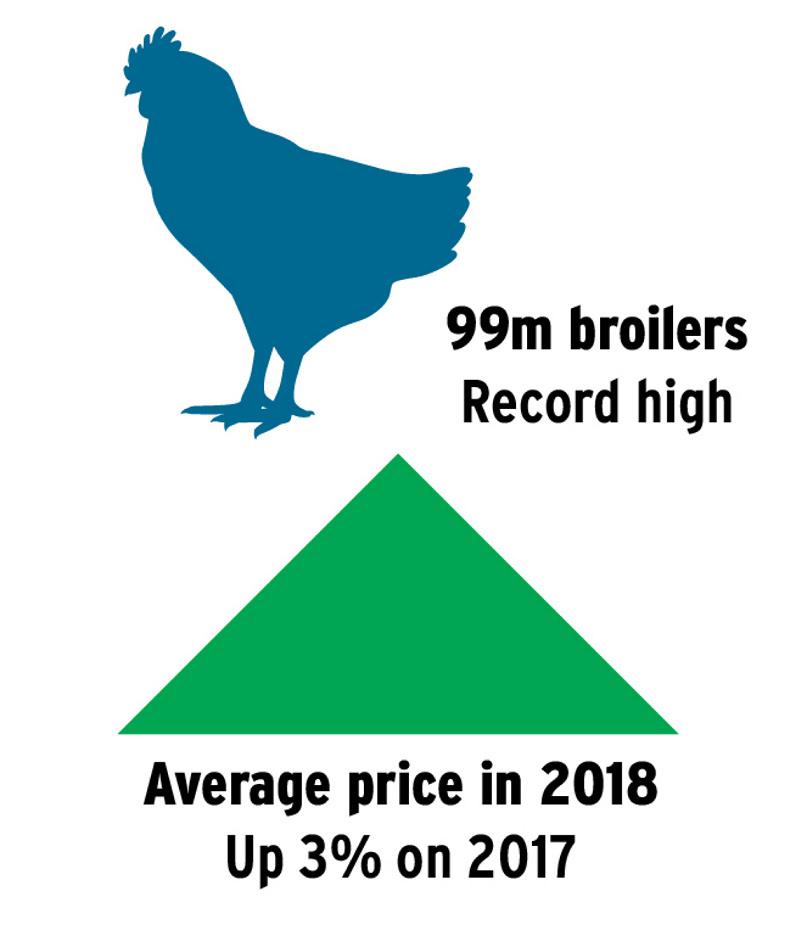

Poultry farmers had, on average, prices 3% above 2017 levels, though they dipped below 2017 levels approaching year end. It was another record year for production, with 99m broilers produced in 2018. Global demand is forecast to continue rising in 2019 and Brazil, which has 20 factories suspended from exporting to the EU because of salmonella, is expected to increase domestic consumption of chicken that will absorb its predicted increased production of 2.6% in 2019.

It is striking how dependent Irish meat exports (with the exception of lamb) are on the UK, with the rest of the EU the next-most-important marketplace. These are the highest-value markets and have a high tariff barrier to external suppliers, though being what are described as mature markets, they have little potential for further growth.

The global growth potential over the next decade is forecast to take place in China and southeast Asia for all species.

Ireland is currently established in the main markets of China, Japan and South Korea for pig meat and with beef approval secured for China in 2018, this market it expected to grow in 2019 as further factory approvals are obtained in addition to the six already doing business there.

Japan is also expected to develop further for beef beyond the 649 tonnes of mainly offals that were sold there in 2018 with the EU-Japan trade agreement coming into effect next month. This will begin a process of reducing beef tariffs from the current 38.5% to 9% over 15 years.

Chinese focus turning to sheepmeatDepartment of Agriculture assistant secretary general Sinéad McPhillips said the Department is acutely aware of the need to maximise access for Irish produce to as wide a portfolio of customers as possible, with the importance of this statement heightened by Brexit, writes Darren Carty.

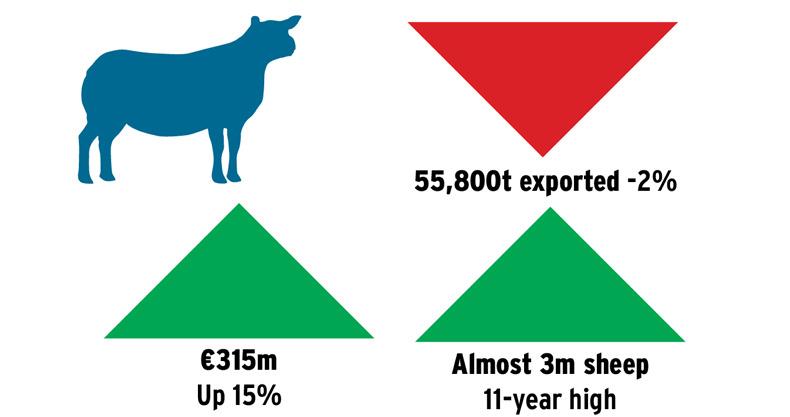

Sinéad said that a sub-group is in place under the Food Wise 2025 programme which is tasked with a continued drive to diversify into new markets. The sheep sector has access to 40 markets, including 15 third country markets, on bilateral or EU trade agreements.

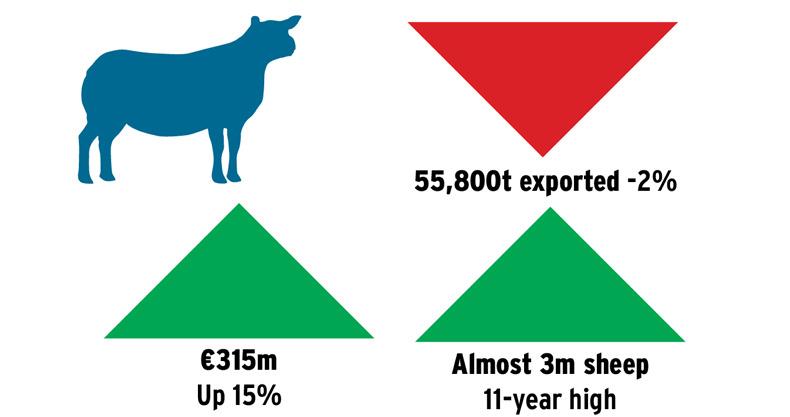

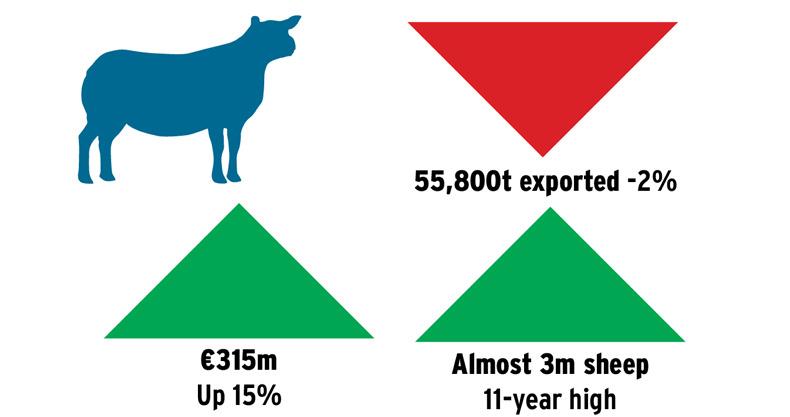

The current focus by the Department for sheepmeat is on gaining access to China. Minister Creed signed an agreement with the Chinese government in 2018 and according to Sinéad the priority is now to advance this to the next stage where meaningful negotiations can take place. She said it was difficult to put a timeline on when market access would be secured but commented that the hope in the short-term is to make significant advancements.

The potential of the market was raised by Bord Bia sheep specialist Declan Fennell in his presentation. China is the largest consumer and importer of sheepmeat globally with volumes imported increasing by a massive 31.6% in 2018 to reach 291,486t for the period January to November.

The market is being serviced mainly at present by New Zealand and Australian sheepmeat but there is scope for exports from Ireland given the magnitude of demand. Declan cautioned however that the market is showing some signs of resistance to higher global prices and appears to operate in cycles of peaks and troughs.

Access to the US market for sheepmeat was raised at previous year’s events as presenting significant opportunity. The market continues to be stifled however by the EU’s TSE status which is said to be preventing trade negotiations from advancing.

While 2018 was a tough year for many Irish farmers coping with a range of weather extremes, particularly in the south and east, meat output increased across all the species.

Bord Bia reported on all to a packed room at its meat marketing seminar, the third industry event of the week following the performance and prospects launch and livestock exports seminar earlier in the week.

Delegates also heard a 10-year view on the prospects for the global meat industry from Richard Brown (Gira Consulting) and the potential of southeast Asia, apart from China, from Ciaran Gallagher who is based in Bord Bia’s Singapore office.

Latest consumer trends, including veganism, were presented and it is impossible to have a food industry event without the issue of Brexit being highlighted.

Carole Lynch from BDO gave an outline of the WTO tariffs that become applicable if there is a no-deal Brexit and of particular interest to the meat traders at the event, the paperwork that is required for trade with the UK as a third country and its cost. The seminar concluded with an explanation of Bord Bia’s meat marketing strategy and its people development programmes.

Beef and live cattle exportsThe Irish beef industry is the largest meat-producing category and Bord Bia’s Mark Zeig reported that with almost 1.8m cattle going through the factories in 2018, it was a 20-year high.

Live exports were also up in numbers but there was a big switch from older cattle to calves, meaning that the value dropped dramatically.

Beef export volumes increased 3% in 2018 to 573,000t carcase weight equivalent (CWE) though value increased just 1% to €2.5bn.

Ireland’s dependence on the UK market is reflected in the 298,000t that it imported from Ireland, which is 52% of all beef exports. The rest of the EU took 250,000t or 44% of total exports meaning that just 4% of Irish beef was sold outside the EU last year including 1,000t to China which opened as a market for the first time.

Trade flows

On prices, it was a mixed year for farmers, with prices climbing from the start of the year and then falling back for the remainder, with the old trend of prices beginning to increase again from November failing to happen in 2018.

Part of the difficulty was EU imports increasing by 11.3% over the course of the year to 288,587t between January and October, while EU exports declined by 6%.

Three-quarters of EU beef imports come from Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay, after a collapse in the Brazilian and Argentinian currencies made their beef particularly competitive in 2018.

Live exports

Following from the live exports seminar the previous day, Joe Burke presented a summary of the main changes in 2018. The profile of live cattle exports from Ireland changed significantly in 2018 compared with the previous year. The Turkish market for adult cattle collapsed from 30,600 in 2017 to 12,900 last year, while calf exports surged by 55% to 158,000 head. Sales to the north were down again to just over 24,645 and just 5,488 cattle were exported to Britain.

Numbers on the ground

The end of 2018 had factory kills over 40,000 in most weeks and looking at the AIMS data up to November, there were 11,000 more male cattle between 24 and 36 months still in the system, though there were 5,000 fewer heifers than the previous year. In the 12 to 24 month category, there were 15,000 less male cattle up to November but 22,000 more heifers.

When it comes to young cattle less than a year old, numbers of males were down 55,000 and females were down 30,000 last year compared with 2017 which suggests the Irish factry kill which has been on an upward trend will level off in 2019.

Bord Bia’s Peter Duggan explained that 2018 was a forgettable year for pig farmers as pig prices fell from September 2017 and have been hovering at around €1.40/kg or below for much of the year, a loss-making position.

Weak prices meant that although the volume of pig meat exports was up 6% on 2017 at 264,000t, the value was down 6% at €666m. Pig numbers were up 3% to 3.75m, of which 466,000 were exported live, predominantly to Northern Ireland.

An already difficult market in 2018 was made worse by the outbreak of African Swine Fever (ASF) and a major cull of the pig herd in China which led to a drop in import demand on an already well-supplied global market. A further complication in 2018 was the launch of a trade war with China by US President Donald Trump which has the potential to cause further disruption this year when US production is forecast to reach a record 12m tonnes.

It is thought that the fallout of the major pig cull in China last year will be a scarcity of supply in 2019 and Ireland and the EU would expect to benefit from any deficit and increase export volumes to China, with hopefully a corresponding lift in farmgate prices.

Poultry farmers had, on average, prices 3% above 2017 levels, though they dipped below 2017 levels approaching year end. It was another record year for production, with 99m broilers produced in 2018. Global demand is forecast to continue rising in 2019 and Brazil, which has 20 factories suspended from exporting to the EU because of salmonella, is expected to increase domestic consumption of chicken that will absorb its predicted increased production of 2.6% in 2019.

It is striking how dependent Irish meat exports (with the exception of lamb) are on the UK, with the rest of the EU the next-most-important marketplace. These are the highest-value markets and have a high tariff barrier to external suppliers, though being what are described as mature markets, they have little potential for further growth.

The global growth potential over the next decade is forecast to take place in China and southeast Asia for all species.

Ireland is currently established in the main markets of China, Japan and South Korea for pig meat and with beef approval secured for China in 2018, this market it expected to grow in 2019 as further factory approvals are obtained in addition to the six already doing business there.

Japan is also expected to develop further for beef beyond the 649 tonnes of mainly offals that were sold there in 2018 with the EU-Japan trade agreement coming into effect next month. This will begin a process of reducing beef tariffs from the current 38.5% to 9% over 15 years.

Chinese focus turning to sheepmeatDepartment of Agriculture assistant secretary general Sinéad McPhillips said the Department is acutely aware of the need to maximise access for Irish produce to as wide a portfolio of customers as possible, with the importance of this statement heightened by Brexit, writes Darren Carty.

Sinéad said that a sub-group is in place under the Food Wise 2025 programme which is tasked with a continued drive to diversify into new markets. The sheep sector has access to 40 markets, including 15 third country markets, on bilateral or EU trade agreements.

The current focus by the Department for sheepmeat is on gaining access to China. Minister Creed signed an agreement with the Chinese government in 2018 and according to Sinéad the priority is now to advance this to the next stage where meaningful negotiations can take place. She said it was difficult to put a timeline on when market access would be secured but commented that the hope in the short-term is to make significant advancements.

The potential of the market was raised by Bord Bia sheep specialist Declan Fennell in his presentation. China is the largest consumer and importer of sheepmeat globally with volumes imported increasing by a massive 31.6% in 2018 to reach 291,486t for the period January to November.

The market is being serviced mainly at present by New Zealand and Australian sheepmeat but there is scope for exports from Ireland given the magnitude of demand. Declan cautioned however that the market is showing some signs of resistance to higher global prices and appears to operate in cycles of peaks and troughs.

Access to the US market for sheepmeat was raised at previous year’s events as presenting significant opportunity. The market continues to be stifled however by the EU’s TSE status which is said to be preventing trade negotiations from advancing.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: