Brexit must be exhausting for British people. It’s certainly testing the endurance of the rest of us. However, it is central to this country’s economic and political future, so we can’t just look away. Just how is Brexit going to play out? Let’s examine the crystal ball.

By the time you read this, it’s fully expected that the British parliament will have passed a motion stating its opposition to a crash out.

Not crashing out will require an extension to Article 50, as a negotiated settlement by 29 March is not possible. An extension will almost certainly be sought, most likely until the end of May. The Brexit time bomb hasn’t been defused, the cord has merely been extended.

If the only impediment to a negotiated settlement is the backstop, as has been stated by Jacob Rees Mogg and company, there is one possible solution: a customs union arrangement between the EU and the UK.

If 634,751 of the leave voters wanted to leave the political union, but maintain a close trading relationship with the EU through some form of negotiated customs partnership, then that would mean a majority of voters support a customs arrangement with the EU

Would this be a betrayal of the people’s will as expressed in the referendum? Probably not.

The vote for Brexit was 17,410,742. People voted to leave the EU for a wide variety of reasons. In total, 16,141,241 voted to remain.

We know all of those wanted to remain in a customs union, they wanted to remain in the political union too. If 634,751 of the leave voters wanted to leave the political union, but maintain a close trading relationship with the EU through some form of negotiated customs partnership, then that would mean a majority of voters support a customs arrangement with the EU.

That’s less than 4% of leave voters. In other words, for the likes of Jacob Rees Mogg to be correct that “leave” means leave the EU’s standards, leave their high levels of traceability of food and other products, leave their elevated level of environmental protection, then over 96% of leave voters would have had to be hard Brexit supporters. That seems unlikely.

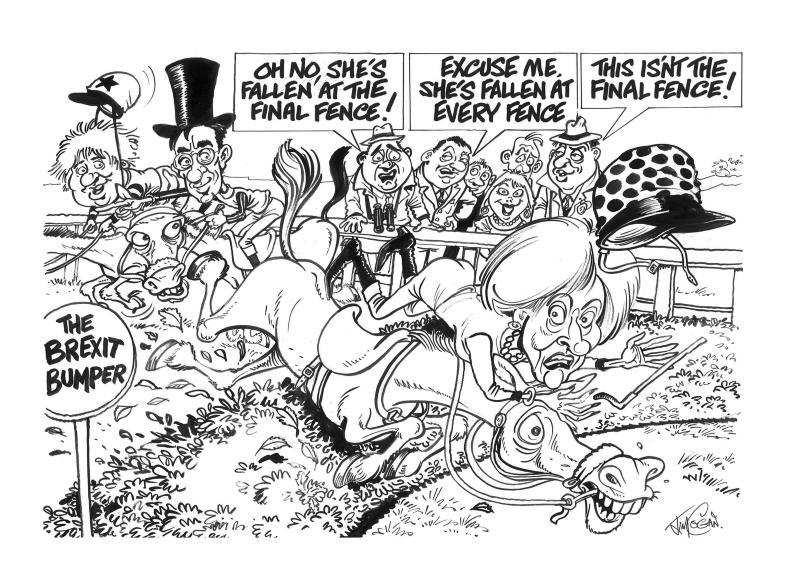

Unfortunately, the hardline Brexiteers convinced British prime minister Theresa May to abandon the idea of maintaining a close customs arrangement early on – it became one of her red lines to rule it out as an option.

The British Labour, for its part, was slow to develop a position, and let precious time pass, before formally adopting remaining in a customs union as its party policy.

It’s not too late. Deciding to stay in a customs union for a medium length of time would allow the British economy to adjust to life outside the EU. It would remove the need for a backstop, as a hard border would no longer threaten stability on this island.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: