There are lots of things that can affect the start of lactation, which can have varying impacts on the cow’s year.

Few are as important as getting calcium management right around calving time.

When managed correctly, it helps the cow motor on into lactation.

When not managed correctly, it can have long-lasting effects on the freshly calved cow.

So, let’s look at why it should be a top priority for farmer and cow this spring.

What happens at calving

About a week before calving, colostrum production is starting in the udder and so begins the cow’s need for more calcium.

Colostrum and milk are rich in calcium, while this is one of its many health benefits and selling points.

The cow must begin mobilising calcium to fill this requirement.

When she starts milking after calving this really ramps up.

In fact, the cow can’t actually digest enough calcium to match this demand in the first weeks of lactation. However, nature as always has answers.

The cow, through a complex process, will draw 90% of this requirement from her bones.

This process of calcium homeostasis is vital for her because calcium plays such a key role in immunity and health in her body.

It is important to understand this process and where the challenges lie on our Irish farms. Then we must look at what we can do to correct it.

Why is calcium so important?

Calcium is a macro element that plays some key roles in the cow’s body.

One of the big ones is muscle function. This is why our classic milk fever cows go down and are weak.

In severe cases they are flat out and eventually the heart muscle fails. This is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to low blood calcium.

Cows eventually become recumbent or lie down flat out and require urgent calcium supplementation.

The big problem is the cows we don’t see that have subclinical problems. This is often referred to as subclinical hypocalcaemia.

It leads to muscle weakness, which can mean lower intakes, problems with uterine infections and even displaced stomachs after calving.

Both the womb and stomachs become weaker (low Ca levels), leading to problems.

The biggest challenge is these cows can have lower dry matter intake after calving, which is the last thing they need.

Having any setbacks around the time of calving and peak metabolic pressure must be avoided. So, getting calcium right can put more milk in the tank.

Another big role calcium plays is in immunity. The cow at calving time has a huge inflammatory process going on.

Her immunity naturally drops but also the challenge from infections rise.

This means she has a big requirement for white blood cells (neutrophils) which are the defenders of infection at this time. Low blood calcium will lead to less of these white blood cells, meaning more risk of infections like metritis or dirty wombs.

She is also at more risk of clinical mastitis. The teat end is a muscle. If it is weak and there are fewer white cells, there can be a spike in mastitis. It is not unusual to see more E coli (watery toxic mastitis) in cows that have low blood calcium.

Finally, at calving time, low blood calcium can see cows that are slower to calve (remember the womb is a big muscle).

I’ve even seen this in heifers that were on the wrong diet which really slowed their calcium homeostasis and leads to subsequent slow calving and problems.

Clinical signs of milk fever

We see fewer and fewer clinical cases of milk fever, where cows go down and require urgent attention.

These cows can be sitting, and after a few hours be flat out. Cows that are down need calcium borogluconate either into a vein or under the skin.

I always give one bottle intravenously slowly and then the second warmed bottle (to help it absorb) under the skin.

Some of these cows also get injured when down or have other problems like E coli mastitis.

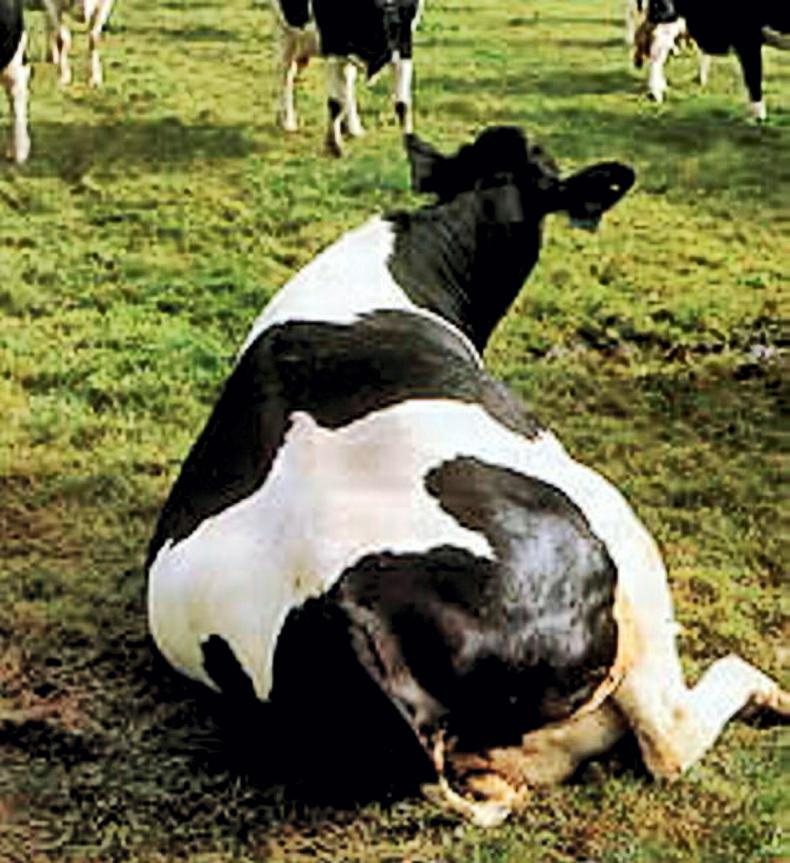

Cows down with milk fever often display a swan neck from muscle weakness.

Don’t presume a cow down only has milk fever. Routinely I give these cows oral energy tonics and warm water by stomach pump.

We don’t want clinical milk fever >1% in our herds. Why? Because for every cow that’s down you could have 10 cows with subclinical symptoms we might see directly.

The more milk a cow produces, the more risk of low blood calcium.

Also, the older a cow is, the slower her process of mobilising calcium from her bones.

Jerseys and Guernseys also are slightly more prone to milk fever because they have lower vitamin D receptors on their bones.

This vitamin is involved in the mobilising process. Cows that are fat and over-conditioned also are at more risk.

While it is important we treat clinical milk fever urgently, for me the big issue now on Irish farms in relation to calcium around calving is subclinical hypocalcaemia.

Why is there a risk at herd level?

There are a number of minerals involved in the mobilisation of calcium from the cow’s bones around calving.

This is why the dry cow diet coming up to calving is so important to get right. One of the key elements is magnesium, which is involved in the process of pulling calcium from the bones by parathyroid hormone release. It also helps make vitamin D so magnesium should be high.

Potassium also plays a role in calcium metabolism.

It locks up magnesium, so can cause problems when it is high.

Calcium itself should be low in the dry cow diet. If it is high, it can actually slow down this process of bone absorption.

Silage that has got a lot of slurry could be high in potassium, which is a risk.

I have seen some problems also where pre-calving minerals had a higher than desired amount of calcium, causing problems.

Diseases at herd level

Another issue we can see with calcium deficiency is more dirty cows after calving with uterine infections.

You may see more displaced stomachs or LDAs as well as other infections from the effects on immunity.

We also have reduced dry matter intake and the risk of subsequent ketosis.

What is the

best treatment?

Individual cow

For the individual downer cow it is best to go intravenously with calcium slowly and have it heated.

With a cow that is standing and showing symptoms of milk fever, an oral calcium bolus probably is the best option.

Never bolus a down cow with a calcium bolus as they can get stuck in the oesophagus.

Once she is standing again, giving a bolus is a good way of topping her up and stopping her going down again.

Clinical milk fever cows get cold so if outside and injured cows haven’t got up, a horse rug is a good idea.

The intravenous or subcutaneous bottle only gives a short spike of calcium so I recommend cows be followed up with at least one calcium bolus when standing.

The cow you suspect is at risk of milk fever but is still standing is probably better getting a bolus rather than a bottle.

They are rapidly absorbed (look for ones containing calcium propionate or Ca chloride). Then always follow this with a second bolus within the 12- to 24-hour window.

At herd level treatments

Most Irish herds can manage the risk by ensuring high pre-calving levels of magnesium in the diet.

People talk about 0.4% kg of DM intake (this works out about 40-50g day per cow). I still think it is worth discussing this with your own nutritionist or vet.

Dietary acidification or altering DCAD works well. This involves feeding specialised anionic salts pre-calving.

This isn’t necessary in most herds unless the DCAD is way off.

Previously people used vitamin D3 injections pre-calving, but I think this is not very effective.

The gold standard for calcium management at herd level is:

1 - Do some forage analysis early to look at risks from low magnesium, high potassium or high calcium.2 - Decide what levels of magnesium need to be fed into cows pre-calving. Decide which route works best on your farm, on/or through feed or through the water being most commonly used.3 - Where a big risk is in place, consider anionic salts supplementation 10 days out from calving. Where an increase in milk fever has occurred, this was often a short-term solution I found worked well combined with monitoring urine pH, looking for pH of 6.5-7.5 pre-calving. 4 - For high at-risk cows, older cows or high-yielding cows, giving calcium boluses routinely works well. Protocol is bolus at calving and repeat the second one at 12-24 hours after calving. There is an option of giving liquids as well. Just be careful with ones containing calcium chloride. It is quite caustic if it goes down the wrong way. 5 - In the middle of a calcium problem in a herd, a calcium bolus on all cows until diet is corrected is also an option.Steps 1 and 2 are where every farm should start.

Conclusion

Calcium after energy is the second most influential factor on the transition management in the dairy cow.

We must move away from thinking about calcium in just the down cow, low blood calcium can have serious negative impacts on our overall herd performance.

There are lots of things that can affect the start of lactation, which can have varying impacts on the cow’s year.

Few are as important as getting calcium management right around calving time.

When managed correctly, it helps the cow motor on into lactation.

When not managed correctly, it can have long-lasting effects on the freshly calved cow.

So, let’s look at why it should be a top priority for farmer and cow this spring.

What happens at calving

About a week before calving, colostrum production is starting in the udder and so begins the cow’s need for more calcium.

Colostrum and milk are rich in calcium, while this is one of its many health benefits and selling points.

The cow must begin mobilising calcium to fill this requirement.

When she starts milking after calving this really ramps up.

In fact, the cow can’t actually digest enough calcium to match this demand in the first weeks of lactation. However, nature as always has answers.

The cow, through a complex process, will draw 90% of this requirement from her bones.

This process of calcium homeostasis is vital for her because calcium plays such a key role in immunity and health in her body.

It is important to understand this process and where the challenges lie on our Irish farms. Then we must look at what we can do to correct it.

Why is calcium so important?

Calcium is a macro element that plays some key roles in the cow’s body.

One of the big ones is muscle function. This is why our classic milk fever cows go down and are weak.

In severe cases they are flat out and eventually the heart muscle fails. This is the tip of the iceberg when it comes to low blood calcium.

Cows eventually become recumbent or lie down flat out and require urgent calcium supplementation.

The big problem is the cows we don’t see that have subclinical problems. This is often referred to as subclinical hypocalcaemia.

It leads to muscle weakness, which can mean lower intakes, problems with uterine infections and even displaced stomachs after calving.

Both the womb and stomachs become weaker (low Ca levels), leading to problems.

The biggest challenge is these cows can have lower dry matter intake after calving, which is the last thing they need.

Having any setbacks around the time of calving and peak metabolic pressure must be avoided. So, getting calcium right can put more milk in the tank.

Another big role calcium plays is in immunity. The cow at calving time has a huge inflammatory process going on.

Her immunity naturally drops but also the challenge from infections rise.

This means she has a big requirement for white blood cells (neutrophils) which are the defenders of infection at this time. Low blood calcium will lead to less of these white blood cells, meaning more risk of infections like metritis or dirty wombs.

She is also at more risk of clinical mastitis. The teat end is a muscle. If it is weak and there are fewer white cells, there can be a spike in mastitis. It is not unusual to see more E coli (watery toxic mastitis) in cows that have low blood calcium.

Finally, at calving time, low blood calcium can see cows that are slower to calve (remember the womb is a big muscle).

I’ve even seen this in heifers that were on the wrong diet which really slowed their calcium homeostasis and leads to subsequent slow calving and problems.

Clinical signs of milk fever

We see fewer and fewer clinical cases of milk fever, where cows go down and require urgent attention.

These cows can be sitting, and after a few hours be flat out. Cows that are down need calcium borogluconate either into a vein or under the skin.

I always give one bottle intravenously slowly and then the second warmed bottle (to help it absorb) under the skin.

Some of these cows also get injured when down or have other problems like E coli mastitis.

Cows down with milk fever often display a swan neck from muscle weakness.

Don’t presume a cow down only has milk fever. Routinely I give these cows oral energy tonics and warm water by stomach pump.

We don’t want clinical milk fever >1% in our herds. Why? Because for every cow that’s down you could have 10 cows with subclinical symptoms we might see directly.

The more milk a cow produces, the more risk of low blood calcium.

Also, the older a cow is, the slower her process of mobilising calcium from her bones.

Jerseys and Guernseys also are slightly more prone to milk fever because they have lower vitamin D receptors on their bones.

This vitamin is involved in the mobilising process. Cows that are fat and over-conditioned also are at more risk.

While it is important we treat clinical milk fever urgently, for me the big issue now on Irish farms in relation to calcium around calving is subclinical hypocalcaemia.

Why is there a risk at herd level?

There are a number of minerals involved in the mobilisation of calcium from the cow’s bones around calving.

This is why the dry cow diet coming up to calving is so important to get right. One of the key elements is magnesium, which is involved in the process of pulling calcium from the bones by parathyroid hormone release. It also helps make vitamin D so magnesium should be high.

Potassium also plays a role in calcium metabolism.

It locks up magnesium, so can cause problems when it is high.

Calcium itself should be low in the dry cow diet. If it is high, it can actually slow down this process of bone absorption.

Silage that has got a lot of slurry could be high in potassium, which is a risk.

I have seen some problems also where pre-calving minerals had a higher than desired amount of calcium, causing problems.

Diseases at herd level

Another issue we can see with calcium deficiency is more dirty cows after calving with uterine infections.

You may see more displaced stomachs or LDAs as well as other infections from the effects on immunity.

We also have reduced dry matter intake and the risk of subsequent ketosis.

What is the

best treatment?

Individual cow

For the individual downer cow it is best to go intravenously with calcium slowly and have it heated.

With a cow that is standing and showing symptoms of milk fever, an oral calcium bolus probably is the best option.

Never bolus a down cow with a calcium bolus as they can get stuck in the oesophagus.

Once she is standing again, giving a bolus is a good way of topping her up and stopping her going down again.

Clinical milk fever cows get cold so if outside and injured cows haven’t got up, a horse rug is a good idea.

The intravenous or subcutaneous bottle only gives a short spike of calcium so I recommend cows be followed up with at least one calcium bolus when standing.

The cow you suspect is at risk of milk fever but is still standing is probably better getting a bolus rather than a bottle.

They are rapidly absorbed (look for ones containing calcium propionate or Ca chloride). Then always follow this with a second bolus within the 12- to 24-hour window.

At herd level treatments

Most Irish herds can manage the risk by ensuring high pre-calving levels of magnesium in the diet.

People talk about 0.4% kg of DM intake (this works out about 40-50g day per cow). I still think it is worth discussing this with your own nutritionist or vet.

Dietary acidification or altering DCAD works well. This involves feeding specialised anionic salts pre-calving.

This isn’t necessary in most herds unless the DCAD is way off.

Previously people used vitamin D3 injections pre-calving, but I think this is not very effective.

The gold standard for calcium management at herd level is:

1 - Do some forage analysis early to look at risks from low magnesium, high potassium or high calcium.2 - Decide what levels of magnesium need to be fed into cows pre-calving. Decide which route works best on your farm, on/or through feed or through the water being most commonly used.3 - Where a big risk is in place, consider anionic salts supplementation 10 days out from calving. Where an increase in milk fever has occurred, this was often a short-term solution I found worked well combined with monitoring urine pH, looking for pH of 6.5-7.5 pre-calving. 4 - For high at-risk cows, older cows or high-yielding cows, giving calcium boluses routinely works well. Protocol is bolus at calving and repeat the second one at 12-24 hours after calving. There is an option of giving liquids as well. Just be careful with ones containing calcium chloride. It is quite caustic if it goes down the wrong way. 5 - In the middle of a calcium problem in a herd, a calcium bolus on all cows until diet is corrected is also an option.Steps 1 and 2 are where every farm should start.

Conclusion

Calcium after energy is the second most influential factor on the transition management in the dairy cow.

We must move away from thinking about calcium in just the down cow, low blood calcium can have serious negative impacts on our overall herd performance.

SHARING OPTIONS