Future demand for all meat, dairy and cereal products is expected to follow a sharp upward trend, driven by a rising global population. This forecast was delivered by Professor Tommy Boland at last week’s British Society of Animal Science conference held in Croke Park.

Tommy’s presentation, which was co-constructed by Paul Kenyon, Massey University, New Zealand, was part of the sheep nutrition session and explored the role of small ruminants in feeding a growing global population.

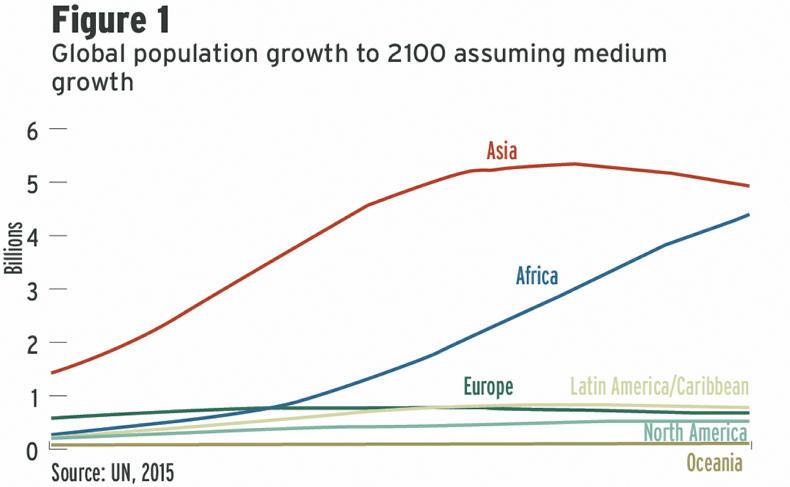

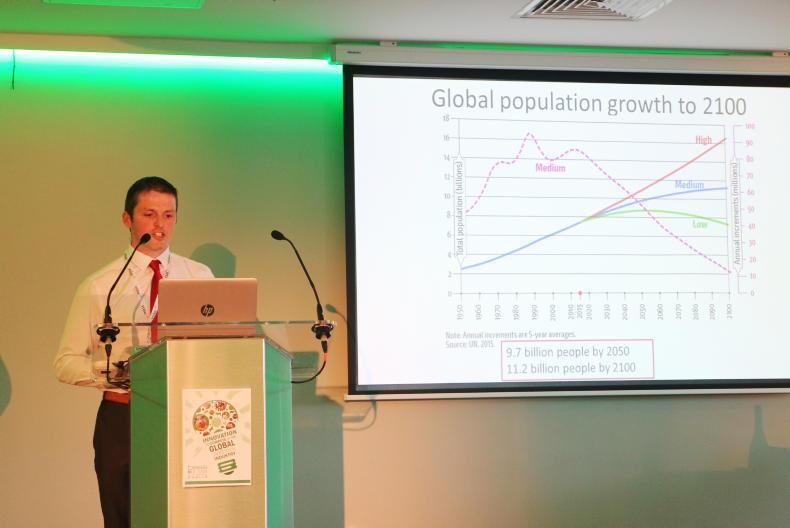

Future predictions can be altered by a magnitude of factors, but the most likely scenario is thought to be medium population growth, which is detailed in Figure 1.

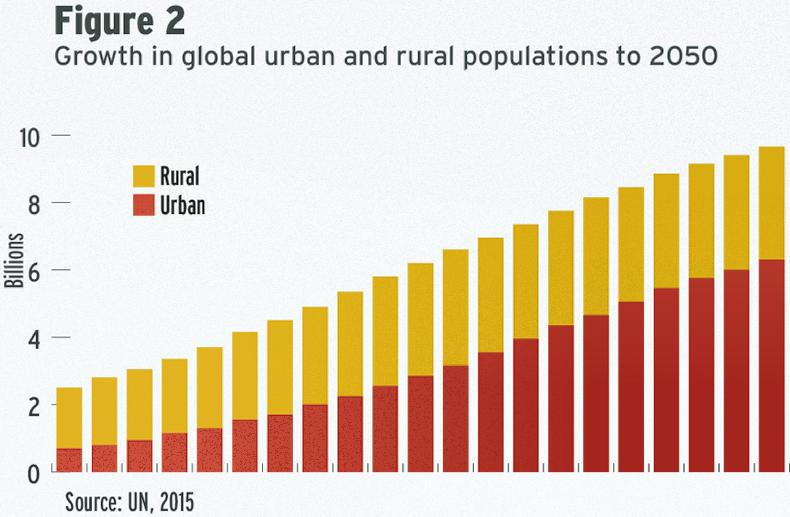

As is very evident, growth is predicted to be dominated by Africa and Asia, with minimal growth expected in other areas. In such a scenario, the global population is expected to reach a staggering 9.7 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100. Much of this growth will take place in urban areas, as reflected in Figure 2.

In addition to population growth, there is also likely to be growth in GDP across all regions. Tommy said that this increased wealth will drive consumption of animal products.

“As developing populations gain increased wealth, they will strive to meet more of their protein requirements from animal sources.

“The big driver of growth in sheepmeat production will be more people eating sheepmeat rather than people eating more sheepmeat, with minimal changes predicted in per capita consumption, while consumption of pork and poultry are predicted to increase on a per-capita basis,” he said.

Poultry and pigmeat have realised the lion’s share of this growth as the population has grown over the last 30 years. This trend is expected to prevail, but there is also expected to be growth across beef, lamb and goat meat.

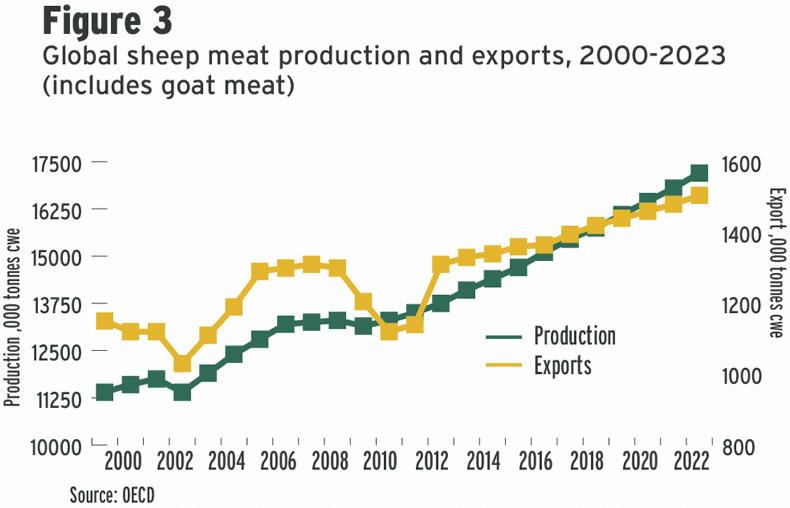

Production of sheep and goat meat on a global stage is forecast to increase from its current level of 14.5Mt to close to 1.6Mt by 2023. Much of this growth will take place in countries which already have a supply deficit and, therefore, there is expected to be minimal change in sheepmeat exports, as detailed in Figure 3.

Tommy also presented analysis of the international meat price index for the main meat types. Sheepmeat compares favourably with beef and poultry, with pigmeat the lowest-priced protein source.

This, he says, contradicts the theory that lamb consumption is restricted solely by price, with tight availability on a global level raised as being an equally important constraint.

As an exporting country, Tommy said that there are more opportunities for growth in sheepmeat production than threats. However, the uncertainty over Brexit makes any predictions perilous.

Sectoral challenges

However, he said the sector was not immune to challenges, with sheep perceived to be poor converters of feed and reported to produce much higher greenhouse gas emissions than other meat and dairy products, with the exception of beef.

Tommy says that a big flaw in much analysis carried out on greenhouse gas emissions or feed utilisation is that no account is taken of the type of feed sheep systems are utilising, whether this land can be used for alternative food production and also the important role sheep play in maintaining the environment.

“Research has continually shown that lamb can be produced with over 90% forage input, with a very low requirement on cereal use.

“Also, when you consider the type of land a high percentage of sheep production in Ireland and in other countries takes place on, there is no alternative food production use. If these areas were not grazed and maintained, they would revert to scrub and lose much of their public good benefits.”

Carbon footprint

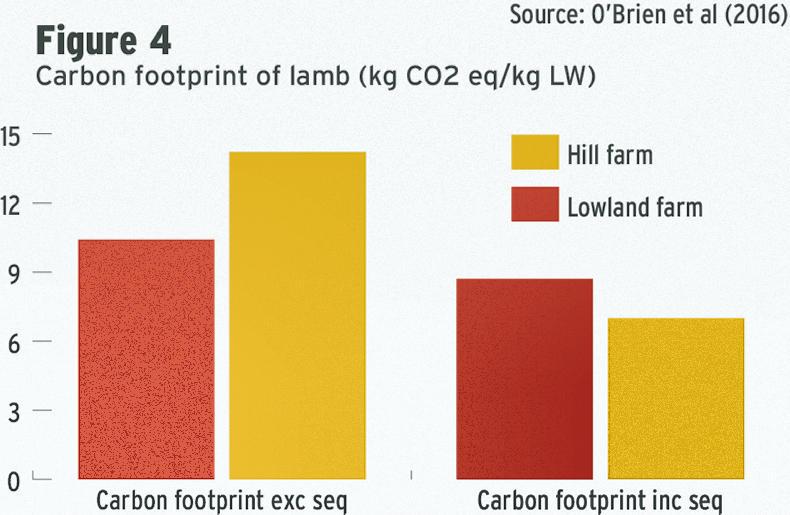

Figure 4 shows the carbon footprint of lamb and, as can be readily seen, sheep systems play a key role in carbon sequestration. Hill sheep systems have a more positive figure, stemming from a much greater capacity to sequester carbon.

Taking the analysis one step further, data presented showed that when consumed, sheepmeat has a superior human edible protein output-to-input ratio than other meat protein sources.

The other challenge which Tommy said could stifle or meet future demand for meat proteins is the advancement in technology of alternative meat sources.

“We saw recently in the media about the burger produced in a laboratory using animal cells. This will not present a challenge overnight, but technology is advancing all the time and it is an area we need to be mindful of.”

Tommy concluded by saying that despite reports stating the contrary, small ruminant production systems are efficient converters of forage to a meat protein source.

He said there is always room to improve in areas such as greenhouse gas emissions and biodiversity, along with sharpening up on animal health measures and performance, which will in turn improve efficiency of production and lower the carbon footprint of each kilo of sheepmeat produced.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: