One of the new aspects in this phase of the BETTER farm programme has been a focus on labour requirements on suckler and beef farms.

Much has been made of the income gulf between drystock and dairy enterprises and while there is no doubt that there is an obvious gap on a whole-farm basis, the story becomes somewhat different when we examine return per hour worked.

I am of the firm belief that through efficient time management, adoption of technologies and installation of proper infrastructure, drystock farmers can match a lot of dairy farmers’ return per hour. Remember too that 40-45% of drystock farms are run on a part-time basis, so time becomes a hugely limiting factor.

How do we calculate this return per hour? By dividing annual hours into net margin (exclusive of subsidies).

In recent years we have seen the dairy sector move towards the inclusion of farmer and family labour in farm E-profit monitors. The argument here is that most of the farm’s margin was going towards a farmer’s own salary and that a business should deliver a profit after paying all of its employees.

Living wage

The reality is that the average drystock farm makes a net loss and depends on subsidies both to prop up the business and as a sole means of income. The goal with BETTER farm is that farmers can earn a good living wage from their farm activities and use their subsidies either to complement this, or as a means of developing their enterprises further.

In July 2017, 11 of our BETTER farm participants started recording their working hours on the first week of every month. They are partaking in the “labour challenge” aspect of the programme. Here we present some of the data generated. While a full year obviously hasn’t been completed yet, the team saw it fitting to investigate the effect that the poor spring had on working hours.

Figure 1 captures the spike in workload that Storm Emma and the subsequent lack of spring brought about. Coinciding with the onset of calving on a lot of farms, average weekly labour requirement was up 10 hours in March versus February.

Employment

In Table 1, we analysed labour and financial performance based on a farmer’s employment situation. Full-time farms were over twice the size of part-time farms on average, and had a working week almost three times longer (93.6 hours versus 35.6).

However, output (€ beef produced) per hour was higher on the part-time farms and this resulted in earnings almost €1.50 per hour higher (€3.36 versus €4.83). Are the part-timers working smarter?

It’s important to take lifestyle and wellbeing into account here – this might look like a big win for part-time farmers, but remember that some are working over 40 hours a week off-farm and coming home to work the equivalent again.

Remember that this data is based on year one – by the end of the programme it is envisaged that earnings will be much higher.

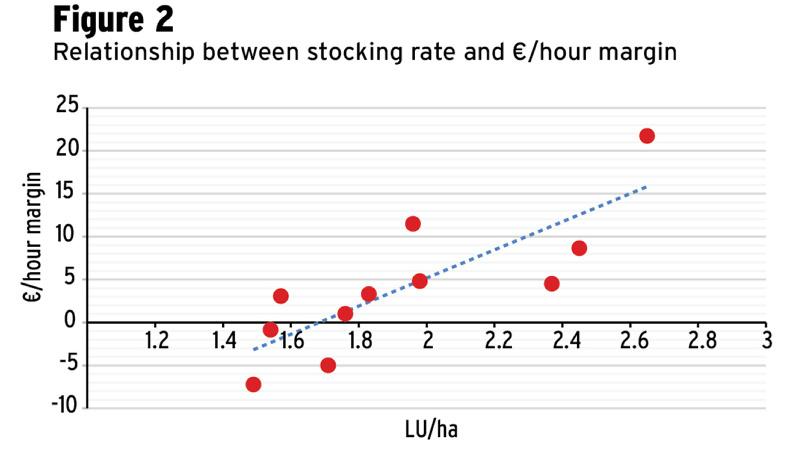

Table 2 breaks up farms by system. As with the profit monitor data, bull finishers again come out on top when it comes to earnings per hour. However, what’s striking is the amount of labour required on these farms. Our bull finishers required 77% higher labour per hectare than the other farmers. This is largely a function of stocking rate being higher on these farms. However, as both Figure 2 and the “€ output per hour” figures demonstrate, the extra numbers on these farms are not in vain – despite working longer hours, there is no dilution effect and turnover (€ output) per hour is still highest with these bull finishers. This translates into the highest earnings per hour at €13.13. Across all farm types, every 0.5LU/ha increasing in stocking rate increased net margin/hour by €8.19. The correlation between the two was 0.81 – very strong.

Comment

What the data highlights is that there is a happy medium to be found. Our farmer with the highest stocking rate and earnings per hour this year also ended up buying in a lot of fodder and feeding meal this spring. He also worked a 40-hour week on top of an off-farm job, though this is seasonal. His strategy was to drive stocking rate on his grazing ground and buy silage in, being located in a region where it was generally readily available. Thankfully he was able to stretch what he had with meal, though of course this was not the plan. This spring might force a rethink here, as with many farms.

For me the standout farmer in this analysis was one of our western participants, Nigel O’Kane. He runs his own plumbing business off-farm, but was able to earn almost €9/hr in a 24-hour farming week. His calving pattern is tight – 26 cows in under eight weeks – and things are kept very simple.

SHARING OPTIONS