When Boortmalt acquired Minch Malt from Greencore in 2010, the future looked a little brighter for that part of our malting industry. At that time the new owners, a subsidiary of the Axereal Co-op in France, linked up with growers via the IFA to help turn around a business which was running at less than 70% of its malting capacity.

Since then, a huge number of changes were introduced which involved streamlining of the supply chain, more company involvement on farms and an increased number of specifications to be met.

These developments also brought the promise of increased demand, which mainly occurred in the distilling sector. Contract holders were then obliged to supply a fixed proportion of their contracted tonnage into higher (brewing) and lower (distilling) protein bands. This requirement, in particular, resulted in significant grower disquiet.

Earlier this week, I spoke with two of the main men in Boortmalt, group CEO Yvan Schaepman and Peter Nallen, group COO. Not surprisingly, price was the first item discussed.

Pricing model

Yvan acknowledges that there is pressure on incomes this year, in particular because of how the pricing model behaved in relation to MATIF. However, Boortmalt believes that the Irish pricing model is delivering for Irish growers and that it is a very unique arrangement forged between the company and the IFA on behalf of growers. While growers will be very aware of the specifics of this arrangement, most other farmers will not.

The arrangement allows for up to four fixed-price selling opportunities between December and June. The price offered reflects the market and demand situation for Boortmalt on those dates. Up to 20% of one’s contract volume can be pre-sold using this mechanism in either 0%, 5%, 10% or 15% lumps. Running alongside this is a weekly option to hedge up to a total of 80% on a price arrangement that relates to MATIF milling wheat futures. This option is available from January to around mid-July.

The hedge operates on a 10% increment, with a maximum of 20% for any single sale. Growers receive a text message on Tuesday and they must notify the company before noon on Wednesday if they wish to partake. The system was developed to help minimise dependence on harvest prices when grain markets tend to be depressed.

Over 50% of grain sold forward

The Boortmalt officials told me that 60% of growers with contracts now avail of the options to sell forward or hedge. The system was designed to sell a little and often and to enable growers to seize selling opportunities. Over half the total contracted tonnage has been sold or hedged in recent years.

In the past two seasons, the total intake at Boortmalt has been either side of 130,000t – about 100,000t of this is for brewing. But demand for distilling barley is growing and this is the main driver of increasing demand. In 2017, when there were only two fixed-price offers, 10.4% out of the maximum 20% was sold at a fixed price alongside about 60,000t which was hedged. The percentages and tonnages were broadly similar in 2016.

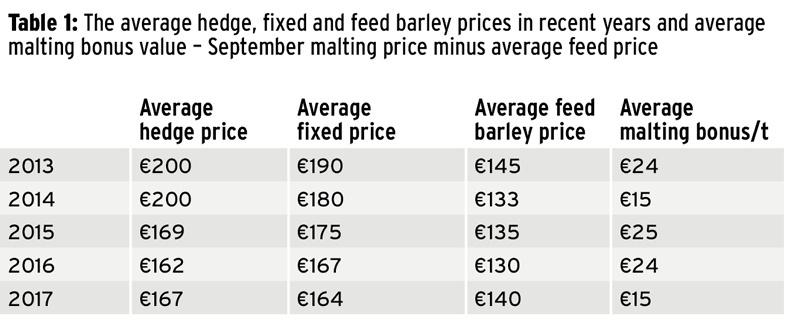

The decision to forward sell remains difficult for growers but many appear to be engaging with the process. According to the figures in Table 1, the model appears to have offered considerable scope to improve the average price.

This shows the average value of all the hedge prices for each year, the average fixed price value each year (individual prices where growers did business could have been higher or lower), the average feed barley price (excluding co-op loyalty or bonus payments) and the average malting bonus paid by the harvest-only price relative to the feed barley prices.

While individuals may have fared better than these malting averages, others will have received feed barley prices which were considerably higher than those shown here. And while it is difficult to value other factors such as being able to cut at higher moistures or being able to dump grain to continue cutting, not being constrained by protein targets, etc, these can be very real factors for some growers.

Specifications

Asked about the increasing number of specifications which malting barley growers have to comply with, Yvan said that these requirements are driven by local markets for, and users of, malt. These criteria are increasingly taken for granted in the industry and the challenge is to stay ahead of the pack to prevent Irish malt slipping into commodity market value.

These specifications are onerous on growers with the risk of rejection being very real, often due to circumstances entirely outside of their control. Skinning last year was just one example of this.

Given the high specs required, Boortmalt says it invests about €1m annually in Ireland in research, advice and other measures to help growers to meet these ever increasing challenges. The recent completion of the Sustainable Agriculture Initiative platform is now another label to put on Irish malt.

Minimum price option

Meeting the increasing demands of customers has been key to preventing malt imports into Ireland in recent years. But, given the risks for growers, I asked if a minimum price could be considered for a product that is so heavily traceable and controlled, and Irish-grown?

Yvan said that this would not be an acceptable solution as it represents a disconnect from the market. While it could certainly be an advantage to growers, he said that it could make Irish malt very expensive in some years and there is real competition in the market. Countries like France, Sweden and the UK are still more than willing to supply malt to Irish users, Yvan said.

He believes that the pricing model is helping to reward growers for the risks and efforts involved. But the direction of travel of the price options in Table 1 indicates the root of the problems being experienced by growers. The price reference within the model has been falling.

Change will be ongoing

Yvan said that Boortmalt will continue to discuss the challenges faced by growers and address them where possible. It would be good if they could develop an alternative pricing model for distilling barley, which can often mean less nitrogen and lower yield to meet the protein specification. Such an option might better focus end-use production on better suited farms.

SHARING OPTIONS