There is a bridge in the Canadian community where I grew up which spans a crystal-clear, rocky river. As a child, I would be mesmerised by the annual pilgrimage of wild Atlantic salmon from the river to the ocean. You could see the silvery fish perfectly from the vantage point of the bridge – and there were always so many.

Atlantic salmon are quite miraculous, when you think about it. They begin life in fresh water; hatching from pebble-like eggs which are laid and buried into a gravelly redd (the name for their breeding grounds), to keep them safe. Once they hatch, they go through several significant changes before turning into silvery smolt and making their way to the North Atlantic Ocean.

After one or more years at sea, they somehow just know when it’s time to make their way back to the very same place where they were first hatched, to breed and lay eggs of their own (this is called spawning).

In Canada, this is the last thing an adult salmon ever does – they don’t survive their epic journey. In Ireland, our rivers are shorter, so it is possible for the salmon to swim back out to sea (or get carried by the current) after their exhausting journey.

Dwindling numbers

Sadly, fewer salmon are making it home to spawn and fewer hatchlings are surviving to adulthood. The most recent estimates from Inland Fisheries Ireland state that wild salmon numbers are down as far as 70% from just 30 years ago. Wild salmon are considered a “keystone species”, which means they are integral to their ecosystem. If removed, the ecosystem will suffer the consequences.

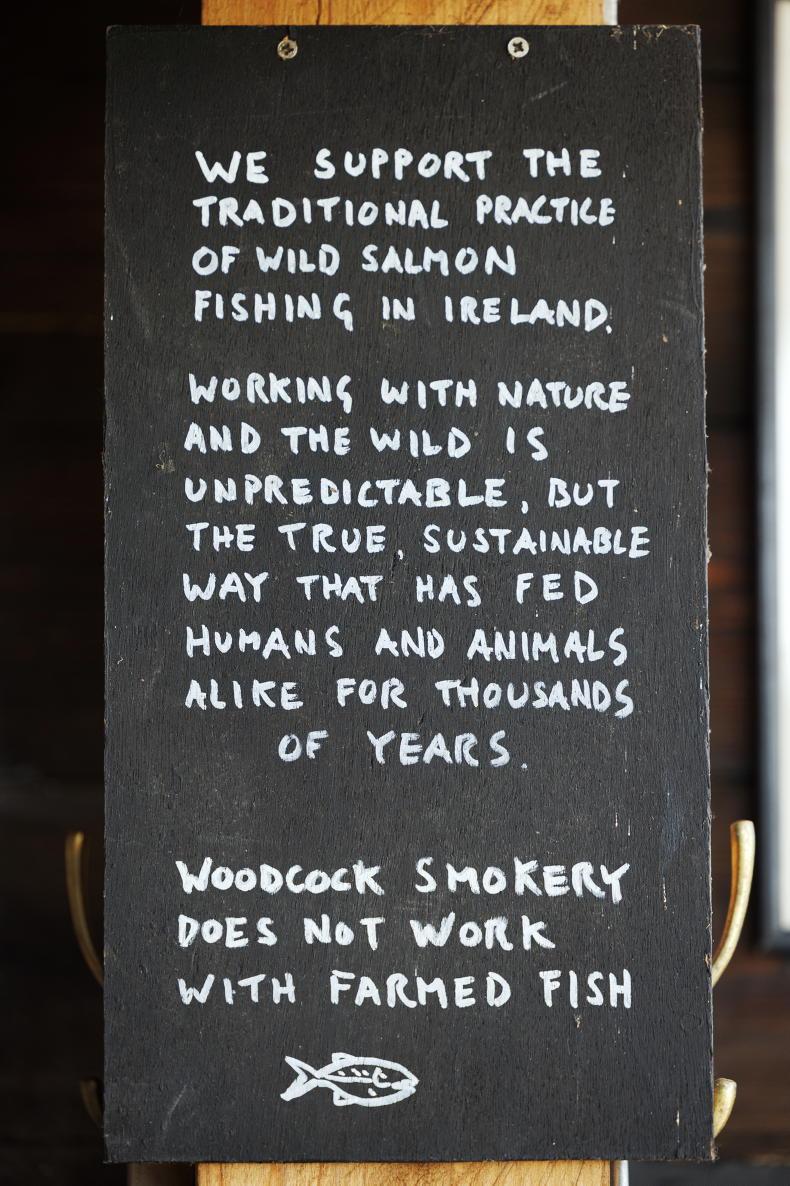

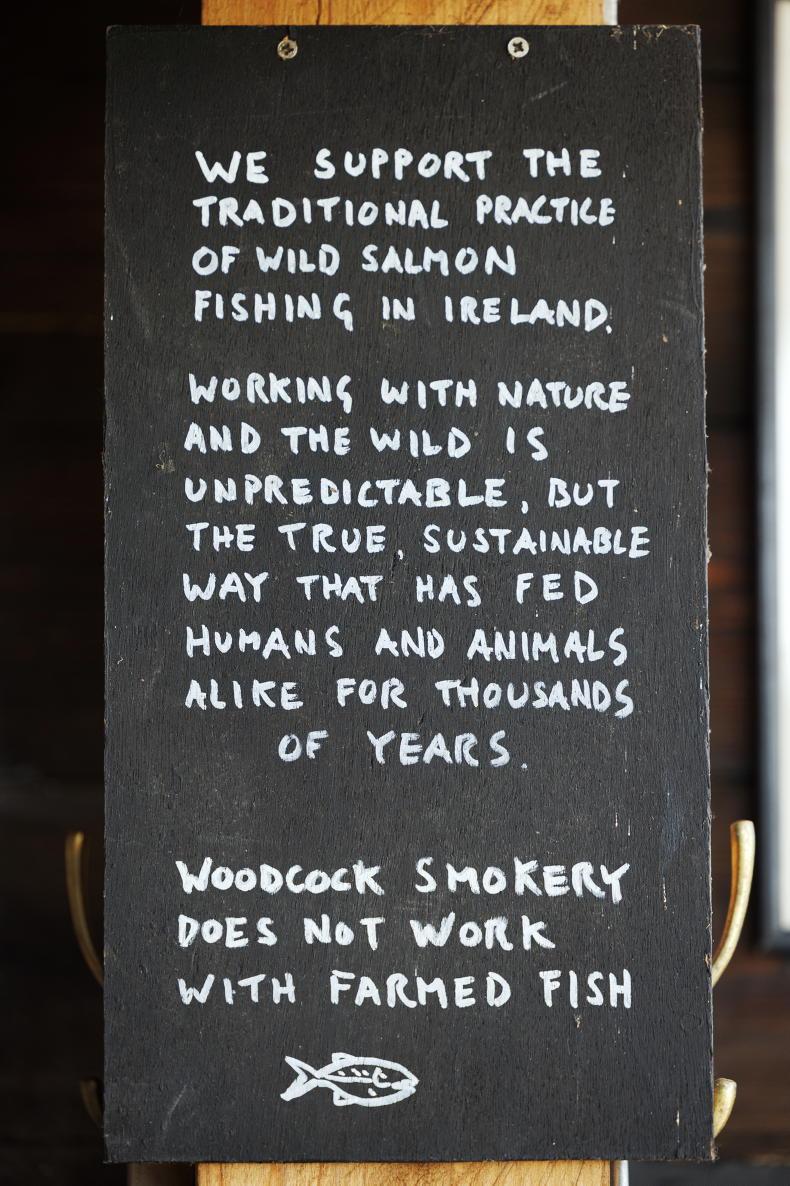

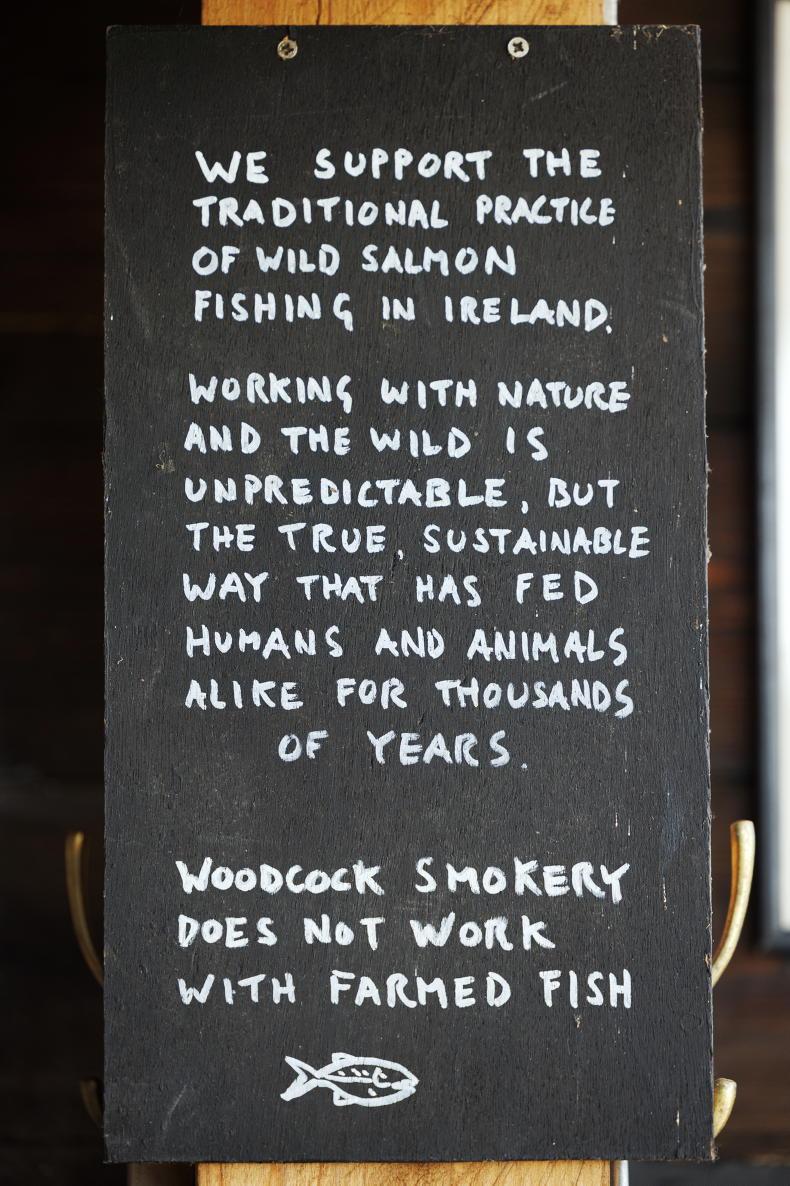

Sally Barnes maintains a firm stance on only purchasing wild fish for her smoked products \ Donal O' Leary

According to the Technical Expert Group on Salmon (TEGOS), which provides an annual assessment for Inland Fisheries Ireland, just 48 of a possible 147 rivers in Ireland can be fully opened for salmon fishing this year. Their “green zones” (open for harvesting) include the Corrib in Co Galway and the Blackwater in Co Cork. Their blue zones (the Suir and the Barrow, for example) are open for catch and release only, while their red zones (including the Upper Shannon around Limerick and into the midlands) are closed for all types of salmon fishing.

They assess these areas by looking at the rates of returning salmon for successful spawning. If there is an identifiable surplus over what they call the “conservation limit”, the area is granted green zone status, while areas reaching an excess of 65% of the conservation limit are granted blue catch and release status.

Woodcock Smokery

Someone well versed in wild Irish salmon is Sally Barnes – an artisan producer and slow food advocate based in west Cork. She owns and operates Woodcock Smokery, which focuses solely on smoking wild fish. Sally tells Irish Country Living that wild salmon are extraordinary creatures.

Her salmon is cold-smoked over beech wood and is sold directly to chefs and consumers online (currently €350/1kg) \ Donal O' Leary

“Wild salmon are my heroes because they’re still there,” she smiles. “They’ve survived since well before the last ice age. They’ve adapted to changing ocean currents. They’re an amazing species with skills and abilities way beyond what we’re capable of – and we’re polluting them out of their own homes.”

Practical beginnings

Sally first began smoking fish as a means of preserving the bounty her then-husband – a fisherman – would bring home. Having no freezer and little culinary experience, she wondered aloud how people originally used to preserve fish.

“They would smoke them,” her husband said. And with that, Sally began honing her craft; smoking her first fish in 1979, then slowly developing a business to supply smoked fish to her local community.

Educational outreach

From there, Sally has made a place for herself among Ireland’s most beloved food producers, winning numerous awards over the years for Woodcock Smokery (including Supreme Champion at the Great Taste awards for her cold-smoked Wild Atlantic Salmon and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Irish Food Writers’ Guild in 2022).

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

Alongside her smoked fish products, she offers fish smoking courses (which can be booked through her website) and provides educational outreach on our indigenous fisheries. She is concerned about the future of west Cork and is angry about how commercial fishing has been managed; particularly since Ireland joined the European Economic Community (the EEC, now the EU) in the 1970s.

“I’ve been in west Cork for 46 years – a long time. It was a different country then,” she notes. “No coastal communities are able to host their young people anymore. In the future, west Cork will be derelict, except for holiday homes – and that’s beyond a tragedy. It all began with giving away 95% of our fish in 1973-74. Ireland gave away 95% of a primary resource in very fertile waters – it was an outrageously silly deal.”

Driftnet ban

Then, in 2007, Ireland banned driftnet fishing which was another blow to rural coastal communities. Today, over a decade since, we are seeing little to no benefit in terms of returning salmon numbers. Sally says the ban was partly introduced from pressures of the international angling lobby, who believed lower salmon numbers in our rivers was the fault of Irish commercial fishing.

“That was the end of day boat fishing,” she says bitterly. “[Up until then], communities in coastal areas were vibrant and had a bit of money coming through, and the fishermen would spend the money locally, not in Dublin or on a shopping trip to Dubai.

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

“What would [maintaining our fishing rights] have been worth to the Irish economy over 50 years?” she muses. “Food and drink exports are so important, but what about our oceans? The ban on drift-netting at sea, here, was the death-knell for inshore fishing.”

Seasonality

Because Sally solely smokes wild caught (never farmed) Irish fish, she is limited in terms of the amounts she can acquire each year. She works seasonally; purchasing salmon from three draft/snapnet fishermen who have commercial quotas on the Blackwater River in Co Cork. Each year, she smokes fewer and fewer salmon.

“One of these fishermen is fourth-generation, but they’re only allowed a third of the quota on the river,” she says. “The anglers are on the water from January to September and they were given a bigger cut. Meanwhile, the commercial fishermen have a lifetime’s worth of experience, skills and knowledge.”

Pollution

River pollution is one obvious reason as to why salmon numbers are lower today than in previous times. Salmon are extremely sensitive to changes in water quality and temperature. Previous to the industrialisation era, salmon numbers were so prolific people grew tired of eating them.

“There’s an article I read some years ago which referred to salmon in the 1920s as being a ‘verminous’ fish,” Sally says. “When there was the big house, the people who were indentured to work there signed a contract for nine years which stated they would not have to eat wild salmon more than twice a week. How can it go from that to where they are now: an endangered keystone species?”

Missed connections

Agricultural run-off is one typical river pollutant, while others come from domestic or community origins. Sally says habitat alterations or loss in rivers are also a huge problem for domestic wild salmon numbers.

“For a while there was a predilection for taking gravel from the riverbeds to make pebbledash for walls, or nice gravel for driveways,” she says. “That ‘gravel’ is terminal moraine [glacial sediment] – left since the last ice age – and it’s pea-sized, which is the same size as the mature salmon egg. It’s vital for them to lay their eggs in.

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

“What humans have lost touch with is that we are all connected,” she continues.

“If you use chemicals at the top of the mountain to kill the bracken, it’s going to run all the way down to the oceans and rivers below. Using biological washing powders and bleachers in your toilet – all of that goes into the main drain.

“Biological powders don’t stop working once they’re flushed. They’re still going. I don’t think people think about it – they just think it gets their clothes nice and white and it’s in the shop, so it must be alright.”

A better approach

For Sally and many other marine enthusiasts, it’s not about giving up on eating fish – it’s about having well-managed fisheries run on a firm base of science. This could not only help increase wild fish numbers, but also revitalise rural communities. Sally says there is always hope to bring wild salmon numbers back, and there are good people out there doing great work.

“I heard of a volunteer group in Meath taking buckets of gravel back up the rivers to try and rehabilitate the redds that the salmon used to spawn in. Literally carrying buckets of gravel. There are some really good people with good energy being put out, there.”

woodcocksmokery.com

We discuss salmon farms, sea lice and what - if anything - can be done to mitigate the effects fin fish farming has on wild fish populations

Read more

Going with the flow in Co Antrim

Murky waters

There is a bridge in the Canadian community where I grew up which spans a crystal-clear, rocky river. As a child, I would be mesmerised by the annual pilgrimage of wild Atlantic salmon from the river to the ocean. You could see the silvery fish perfectly from the vantage point of the bridge – and there were always so many.

Atlantic salmon are quite miraculous, when you think about it. They begin life in fresh water; hatching from pebble-like eggs which are laid and buried into a gravelly redd (the name for their breeding grounds), to keep them safe. Once they hatch, they go through several significant changes before turning into silvery smolt and making their way to the North Atlantic Ocean.

After one or more years at sea, they somehow just know when it’s time to make their way back to the very same place where they were first hatched, to breed and lay eggs of their own (this is called spawning).

In Canada, this is the last thing an adult salmon ever does – they don’t survive their epic journey. In Ireland, our rivers are shorter, so it is possible for the salmon to swim back out to sea (or get carried by the current) after their exhausting journey.

Dwindling numbers

Sadly, fewer salmon are making it home to spawn and fewer hatchlings are surviving to adulthood. The most recent estimates from Inland Fisheries Ireland state that wild salmon numbers are down as far as 70% from just 30 years ago. Wild salmon are considered a “keystone species”, which means they are integral to their ecosystem. If removed, the ecosystem will suffer the consequences.

Sally Barnes maintains a firm stance on only purchasing wild fish for her smoked products \ Donal O' Leary

According to the Technical Expert Group on Salmon (TEGOS), which provides an annual assessment for Inland Fisheries Ireland, just 48 of a possible 147 rivers in Ireland can be fully opened for salmon fishing this year. Their “green zones” (open for harvesting) include the Corrib in Co Galway and the Blackwater in Co Cork. Their blue zones (the Suir and the Barrow, for example) are open for catch and release only, while their red zones (including the Upper Shannon around Limerick and into the midlands) are closed for all types of salmon fishing.

They assess these areas by looking at the rates of returning salmon for successful spawning. If there is an identifiable surplus over what they call the “conservation limit”, the area is granted green zone status, while areas reaching an excess of 65% of the conservation limit are granted blue catch and release status.

Woodcock Smokery

Someone well versed in wild Irish salmon is Sally Barnes – an artisan producer and slow food advocate based in west Cork. She owns and operates Woodcock Smokery, which focuses solely on smoking wild fish. Sally tells Irish Country Living that wild salmon are extraordinary creatures.

Her salmon is cold-smoked over beech wood and is sold directly to chefs and consumers online (currently €350/1kg) \ Donal O' Leary

“Wild salmon are my heroes because they’re still there,” she smiles. “They’ve survived since well before the last ice age. They’ve adapted to changing ocean currents. They’re an amazing species with skills and abilities way beyond what we’re capable of – and we’re polluting them out of their own homes.”

Practical beginnings

Sally first began smoking fish as a means of preserving the bounty her then-husband – a fisherman – would bring home. Having no freezer and little culinary experience, she wondered aloud how people originally used to preserve fish.

“They would smoke them,” her husband said. And with that, Sally began honing her craft; smoking her first fish in 1979, then slowly developing a business to supply smoked fish to her local community.

Educational outreach

From there, Sally has made a place for herself among Ireland’s most beloved food producers, winning numerous awards over the years for Woodcock Smokery (including Supreme Champion at the Great Taste awards for her cold-smoked Wild Atlantic Salmon and a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Irish Food Writers’ Guild in 2022).

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

Alongside her smoked fish products, she offers fish smoking courses (which can be booked through her website) and provides educational outreach on our indigenous fisheries. She is concerned about the future of west Cork and is angry about how commercial fishing has been managed; particularly since Ireland joined the European Economic Community (the EEC, now the EU) in the 1970s.

“I’ve been in west Cork for 46 years – a long time. It was a different country then,” she notes. “No coastal communities are able to host their young people anymore. In the future, west Cork will be derelict, except for holiday homes – and that’s beyond a tragedy. It all began with giving away 95% of our fish in 1973-74. Ireland gave away 95% of a primary resource in very fertile waters – it was an outrageously silly deal.”

Driftnet ban

Then, in 2007, Ireland banned driftnet fishing which was another blow to rural coastal communities. Today, over a decade since, we are seeing little to no benefit in terms of returning salmon numbers. Sally says the ban was partly introduced from pressures of the international angling lobby, who believed lower salmon numbers in our rivers was the fault of Irish commercial fishing.

“That was the end of day boat fishing,” she says bitterly. “[Up until then], communities in coastal areas were vibrant and had a bit of money coming through, and the fishermen would spend the money locally, not in Dublin or on a shopping trip to Dubai.

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

“What would [maintaining our fishing rights] have been worth to the Irish economy over 50 years?” she muses. “Food and drink exports are so important, but what about our oceans? The ban on drift-netting at sea, here, was the death-knell for inshore fishing.”

Seasonality

Because Sally solely smokes wild caught (never farmed) Irish fish, she is limited in terms of the amounts she can acquire each year. She works seasonally; purchasing salmon from three draft/snapnet fishermen who have commercial quotas on the Blackwater River in Co Cork. Each year, she smokes fewer and fewer salmon.

“One of these fishermen is fourth-generation, but they’re only allowed a third of the quota on the river,” she says. “The anglers are on the water from January to September and they were given a bigger cut. Meanwhile, the commercial fishermen have a lifetime’s worth of experience, skills and knowledge.”

Pollution

River pollution is one obvious reason as to why salmon numbers are lower today than in previous times. Salmon are extremely sensitive to changes in water quality and temperature. Previous to the industrialisation era, salmon numbers were so prolific people grew tired of eating them.

“There’s an article I read some years ago which referred to salmon in the 1920s as being a ‘verminous’ fish,” Sally says. “When there was the big house, the people who were indentured to work there signed a contract for nine years which stated they would not have to eat wild salmon more than twice a week. How can it go from that to where they are now: an endangered keystone species?”

Missed connections

Agricultural run-off is one typical river pollutant, while others come from domestic or community origins. Sally says habitat alterations or loss in rivers are also a huge problem for domestic wild salmon numbers.

“For a while there was a predilection for taking gravel from the riverbeds to make pebbledash for walls, or nice gravel for driveways,” she says. “That ‘gravel’ is terminal moraine [glacial sediment] – left since the last ice age – and it’s pea-sized, which is the same size as the mature salmon egg. It’s vital for them to lay their eggs in.

Sally Barnes owns and operates Woodcock Smokery in west Cork. \ Donal O' Leary

“What humans have lost touch with is that we are all connected,” she continues.

“If you use chemicals at the top of the mountain to kill the bracken, it’s going to run all the way down to the oceans and rivers below. Using biological washing powders and bleachers in your toilet – all of that goes into the main drain.

“Biological powders don’t stop working once they’re flushed. They’re still going. I don’t think people think about it – they just think it gets their clothes nice and white and it’s in the shop, so it must be alright.”

A better approach

For Sally and many other marine enthusiasts, it’s not about giving up on eating fish – it’s about having well-managed fisheries run on a firm base of science. This could not only help increase wild fish numbers, but also revitalise rural communities. Sally says there is always hope to bring wild salmon numbers back, and there are good people out there doing great work.

“I heard of a volunteer group in Meath taking buckets of gravel back up the rivers to try and rehabilitate the redds that the salmon used to spawn in. Literally carrying buckets of gravel. There are some really good people with good energy being put out, there.”

woodcocksmokery.com

We discuss salmon farms, sea lice and what - if anything - can be done to mitigate the effects fin fish farming has on wild fish populations

Read more

Going with the flow in Co Antrim

Murky waters

SHARING OPTIONS